![]()

1 Platypus

TAXIDERMY SPECIMEN

Evolution Can Only Work With What It Has Got

Science is supposed to be unbiased, but scientists are not. We have our favourites and our passions, and mine is the platypus. I could have used this bizarre Australian to illustrate any number of nature’s mechanisms or incredible stories in the history of zoology, but I wanted to use it to demonstrate on a very simple idea about how evolution works, as a means to begin the book: Evolution can only work with what it has got.

One thing that evolution had at the end of the Triassic period, a little over 200 million years ago, was the synapsids – a group of reptile-like animals which would give rise to mammals. Triassic synapsids had a lot of characteristics that we might call reptilian. This is because they shared a recent evolutionary history with the groups that would become crocodiles, dinosaurs, lizards and turtles. They did things that reptiles do, like laying eggs and walking with bent elbows and knees, with their limbs held out at right angles to their bodies (or at least partially).

This is the ancestral frame that evolution had to work with. All new developments would have to start from here. This means that the first mammals would have shared a lot of characteristics with their reptilian forebears.

Platypuses are often described as ‘primitive’ because throughout their long evolutionary history they have retained these ancient ancestral features. Platypuses, and their closest living relatives the echidnas, still walk with bent elbows and knees, and still lay eggs, just like their Triassic relatives.

Platypuses are mammals, and laying eggs might not seem like a very mammalian thing to do. Many people are under the impression that all mammals give birth to live young. There are a few unique defining characteristics of all living mammals, but live-birthing is not one of them. They include the presence of hair, three inner-ear bones, a specialised ankle joint and a single bone forming either side of the lower jaw (reptiles have seven), and the ability to produce milk (mammary is the root of the word mammal). Platypuses have all of these features. (Platypuses do not truly suckle their young, though, as they don’t have nipples. However, they do have mammary glands: the milk kind of sweats out of them, and the babies lap it up.)

Together platypuses and echidnas form the order Monotremata, so named for their cloaca: a single (monos) hole (trema) for all their urogenitary functions. Like reptiles, they do all their defecating, urinating, mating and birthing through this one single opening. It is these reptilian features that have earned platypuses their ‘primitive’ reputation. However, on to this ancient template platypuses have added some of the most advanced characteristics of any mammal. This is the reason why I get so excited about platypuses.

First, male platypuses are among the only venomous mammals. They have a horny spur on their heels attached to a venom gland, which is used during sexual competition. (The venom is said to be excruciating and long-lasting for humans.) The males of many species have developed myriad ways to secure sexual success, from giant antlers to absurd decoration. Platypuses are the only mammal to use venom to fight off rivals.

Second, they are one of only a tiny number of mammals known to be capable of electroreception (the others are their close relatives the echidnas, and one species of dolphin): they can detect electricity through their bills. Platypuses are restricted to the lakes and rivers of Tasmania and eastern Australia, where they are reasonably common. They use their power of electroreception to hunt worms and tiny crustaceans. Muscular movement in animals is controlled by electrical impulses. Little is known about platypus feeding, but it is assumed that platypuses can locate their prey buried under silt by sensing these electrical impulses with their bills. They gather food up in little pouches at the base of the bill and then mash it up (adult platypuses have no teeth) with their rubbery bills when on the surface.

In the history of the platypus, evolution started with a ‘primitive’, reptile-like template. Without changing much of this ancient frame, incredibly advanced features were added. This demonstrates that a modern species can never itself be called ‘primitive’ – only the characteristics it has inherited from its ancestors. Neither can a species be considered ‘advanced’, as although it may have evolved some brand new tricks, it still retains those basic elements that have stood the test of time and are found to be still useful now.

When Europeans first discovered platypuses at the end of the eighteenth century they caused quite a stir. The first specimens to reach England – preserved in barrels of brandy or as dried skins – were thought to be hoaxes, made from at least three animals sewn together. There are (probably apocryphal) stories that the earliest specimen to reach what is now the Natural History Museum in London has visible plier marks on its bill, where the curator tried to wrench it off to demonstrate it had been sewn together as a fake. Indeed, in the Grant Museum of Zoology, where I work, there is a bill that has been detached from its body in a crude manner that implies it cannot have been carefully dissected away, which may be the result of similar treatment.

With its bizarre mix of characteristics, both novel and ancient, the platypus did not fit into the existing animal groups that scientists had conceived, and there was great debate over where to place it. Eventually, entirely new groups were created to accommodate it.

Taxonomy aside, it took nearly a century to settle the argument over whether it truly did lay eggs. Perhaps the religiously minded scientific elite took exception to the idea that something which was clearly a mammal could do something so reptilian – something that might drag our noble class down into the mud and slime.

Robert Grant – the founder of the Grant Museum and an early proponent of evolution (he had a huge influence on sparking Darwin’s thinking) – was a strong supporter of egg-laying in platypuses. Perhaps he used this taxidermy specimen in his search for evidence.

![]()

Part 1

Understanding Diversity

PUTTING ANIMALS IN ORDER

The human desire to classify is perhaps at its strongest when it comes to natural history. From our childhood years we are taught to put the animals we encounter in museums, living rooms and the natural environment into discrete categories. At school and on television we are taught the differences between groups like amphibians and fish.

Thomas Henry Huxley, one of the greatest biologists of the nineteenth century and a man who can take a lot of credit for making Darwin’s work accepted by the Victorian scientific community, said this:

To a person uninstructed in natural history, his country or sea-side stroll is a walk through a gallery filled with wonderful works of art, nine-tenths of which have their faces turned to the wall. Teach him something of natural history, and you place in his hands a catalogue of those which are worth turning around.1

He was right. Knowing what you are looking at – in both nature and the art gallery in Huxley’s analogy – is half the joy. But we can’t become ‘instructed’ in everything. The world is an endless purveyor of wonders too numerable to memorise. To make sense of the 1.5 million species so far described (and there may be 100 million undescribed species), natural historians have to come up with a system for arranging them and information about them.

This proved tricky until 1735, when Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus proposed a system for putting species into hierarchical groups, and it stuck. In today’s terms, a rat can be a rat, a rodent, a mammal, a vertebrate and an animal all at once. Such taxonomic thinking is really important for how we understand the world and our place in it, as each of these terms comes with implicit information about how they relate to other groups. It neatly puts the world into boxes. Although it certainly wasn’t Linnaeus’ intention (he believed that studying nature would reveal the divine order of God’s creation), hierarchical taxonomies tell us a lot about an animal’s evolutionary history, as by their nature they show what came from what. This information is real and truthful, but, as is often said, a bee doesn’t care that it is a bee. Taxonomy – the science of putting things into groups – is a rigid human construct that is forced on top of the cacophonous uncertainty of the real wild world.

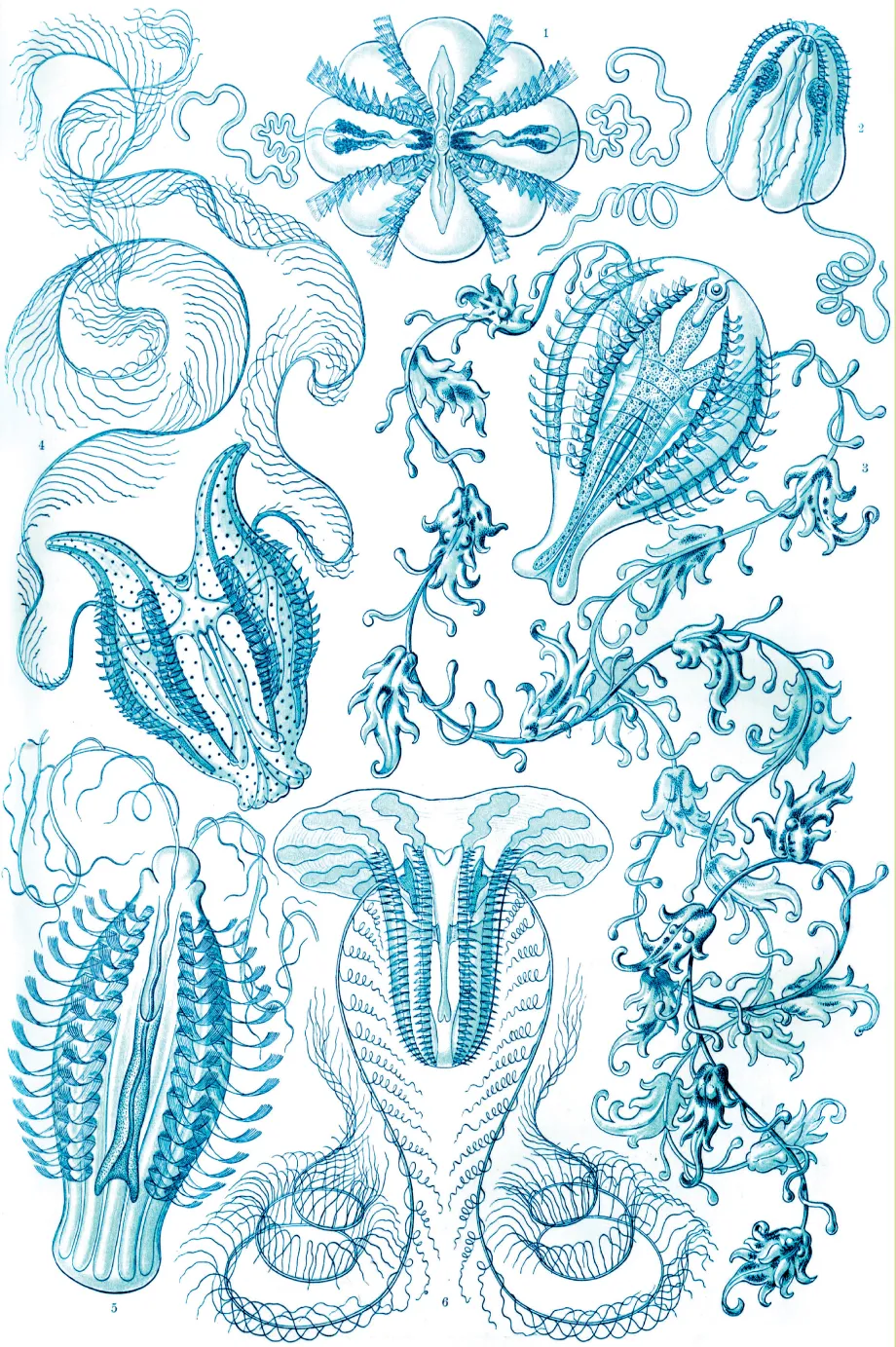

Comb jelly illustrations from Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature), a 1904 book by German biologist Ernst Haeckel (see object 18).

One of the central tenets of modern taxonomy is that every group has to include, by definition, all of the groups that evolve from it. So rats did not stop being mammals when the rodent group branched off the evolutionary tree. Every branch on the tree of life is considered to be a member of all its parent branches.

This means, for example, there can be no definition of fishes that does not include everything that evolved from fishes. Following this logic, you could argue that as amphibians evolved from fishes, amphibians are fishes. Mammals evolved from animals that evolved from fishes, so mammals are fishes. We are fish. While every biologist knows this conundrum, and that there is no biological definition for what most people consider ‘fishes’, they decide not to worry about it because it’s helpful to think about living swimming ‘fishes’ as a group. Taxonomy is useful and makes a lot of sense, until it doesn’t.

Similarly we have all been taught that the animal world can be divided into vertebrates and invertebrates. This is a very handy division, but it suffers from the same problem as ‘fishes’: as vertebrates evolved from invertebrates, every single species of animal there has ever been is an invertebrate. Given that this means that animal and invertebrate are taxonomically synonymous, we just have to agree to ignore that and carry on as normal.

The boxes that taxonomy forces around the natural world come in a set sequence of ever-more specific groupings. The largest in common use is kingdom, and this book focusses on just one of them – the animals. The simplest hierarchy of groups goes like this:

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

And for us, that hierarchy would look like this:

Kingdom: Animal

Phylum: Chordate

Class: Mammal

Order: Primates

Family: Great apes

Genus: Homo

Species: Homo sapiens

Below the kingdom level, the next sub-grouping is phylum (plural: phyla). There are commonly held to be thirty-five animal phyla. This first section of the book makes an attempt to give coverage to some of the diversity of life that doesn’t enjoy a lot of limelight. I could have chosen to dedicate a chapter to each of the phyla, but I haven’t.

That’s because evolution has produced many different ways of being a worm: about half of the phyla are distinctly wormish. I apologise to worm-fanciers out there, but given that many of these phyla contain rather few species, and that I have a lot more to say about the less vermicular animals of the world, I opted not to give them the proportional coverage you may think they deserve.

Instead, here follow eighteen different objects representing eighteen of the major groupings of the animal kingdom. It hopefully demonstrates most of the key ways there are of being an animal.

A few of which are worms.

![]()

2 Elephant Ear Sponge

DRY SPECIMEN

Sponges: The Poriferans

For most of the history of life all organisms were single cells. A giant leap was made when dividing cells didn’t separate from one another and became integrated to form a simple multicellular organism. Only then could huge steps be made to diversify the shapes, sizes and behaviours we see in the biological world today.

Sponges are among the oldest known animal fossils, dating back to the late Precambrian period, 580 million years ago. They branched off extremely early in the history of animals, separating them from the groups that have far more complex structures. They have one of the most simple body plans of all animals. They only have a small number of different types of cell, ...