![]()

1

The Smuts Report

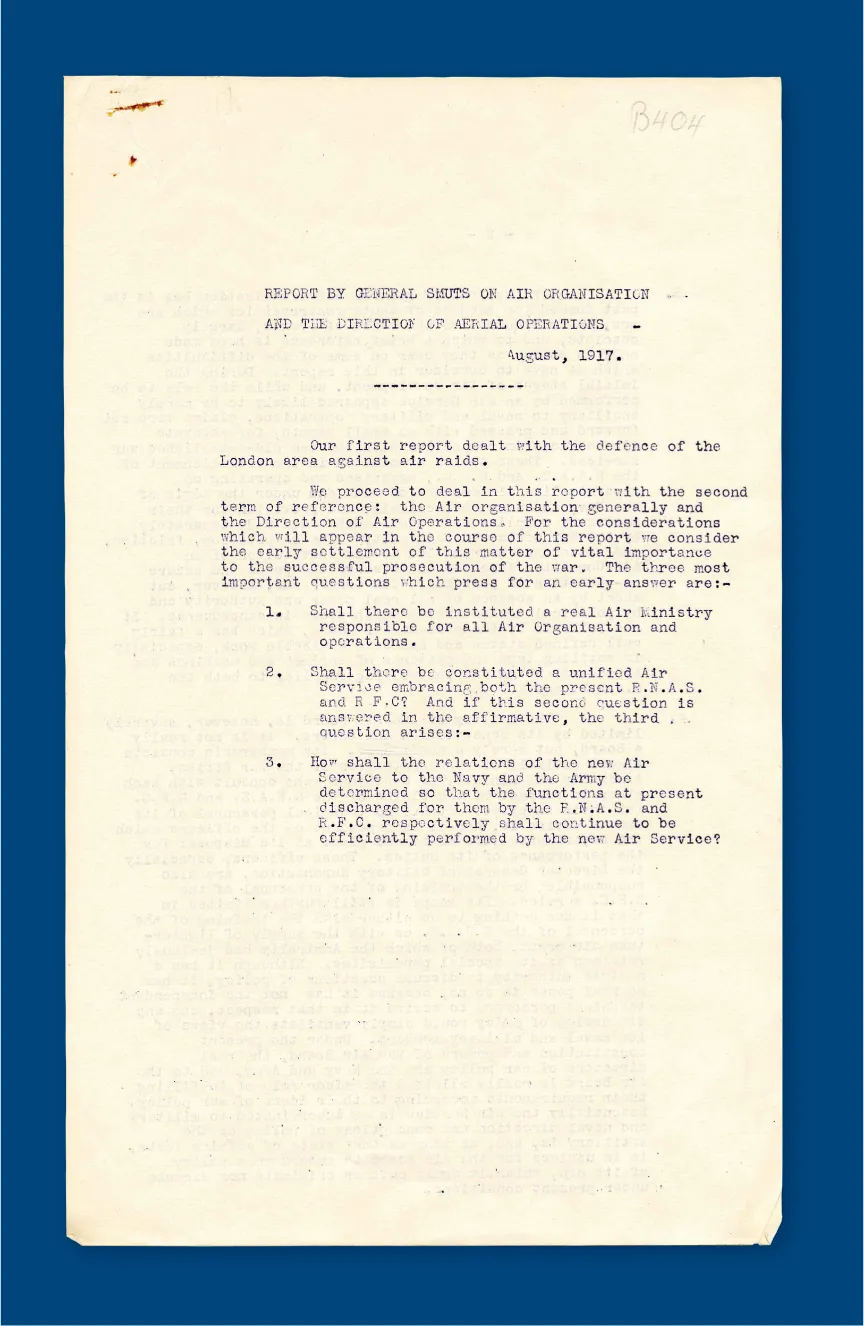

DECIDING WHAT SHOULD be object number one, and, therefore, what should start the story of the Royal Air Force’s 100 years, was never going to be easy. People will have their own ideas but I have decided to go for a simple document, known as the Smuts Report, as it was this report that was instrumental in leading to the formation of the Royal Air Force.

With German bombing of London during 1917 causing public outrage, the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, commissioned a report for the Imperial War Cabinet – comprising the prime ministers and other senior officials of the Commonwealth nations – to co-ordinate military policy. The report was to be prepared by the prominent South African military leader, General Jan Smuts, and was to report on two key issues: firstly, to address the arrangements for Home Defence against the increasing number of enemy bombing raids on Britain and, secondly, to address the air organisation in general and the direction of aerial operations.

In response to the latter, Smuts recommended the establishment of a separate air service. It was a recommendation that was to be accepted by the War Cabinet, with Smuts then asked to lead an Air Organisation Committee to put the recommendation into effect. Much of the detailed work was led by Lieutenant General Sir David Henderson, a senior leader of British military aviation during the First World War, and in early 1918 Lord Rothermere was appointed as the first Secretary of State for Air, with the establishment of an Air Council. And so, it was the Smuts Report, which had recommended the creation of a single air force to hit back at Germany, that led to the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) on 1 April 1918 to become the Royal Air Force (RAF) under the newly created Air Ministry.

Country of Origin:

UK

Date:

August 1917

Location:

RAF Museum

Hendon, London

(© RAF Museum)

The RAF was the world’s first independent air force (i.e., it was independent of army or navy control) and by the end of the First World War it had become the most powerful air force in the world with some 22,000 aircraft and more than 313,000 personnel (there had been just over 2,000 serving with the RFC and RNAS at the outbreak of war). However, the RAF had only been considered a temporary organisation on its formation, and for the next few months its future was uncertain. It would not be until the dust had settled long after the First World War was over that the cabinet decided to retain the country’s third service – although the RAF was to be reduced in strength to 35,000. The rest, as they say, is history.

2

Trenchard’s Boots

AT FIRST GLANCE, a pair of boots might not seem particularly interesting or historic but in this case the boots belonged to Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard GCB OM GCVO DSO, a man often remembered as the Father of the Royal Air Force and a name that has become synonymous with the RAF and its strategic use of air power. If it was the Smuts Report that was instrumental in leading to the formation of the RAF, then it was the vision of Trenchard that made it work.

Trenchard was a former army officer. Born in Taunton in 1873, he had served as a young man in India and the Boer War, as well as West Africa where he commanded the Southern Nigeria Regiment. Encouraged by a colleague, he learned to fly in 1912 at the age of 39. Although he was no youngster, Trenchard quickly gained his aviator’s certificate with just a couple of weeks of tuition and not much more than an hour spent in the air. At the outbreak of the First World War he was given command of the Military Wing with responsibility for the RFC at home, specifically for the training of replacement personnel and the raising of new squadrons for service overseas. But Trenchard was disappointed to have been left at home. He was keen to get to the front line and finally got his chance when he was given command of the RFC’s First Wing in France. Then, in 1915, he was promoted to brigadier to command the RFC in the field, an appointment he held for more than two years and during which he was further promoted to the rank of major general.

Country of Origin:

UK

Date: 1918

Location: RAF

College Cranwell, Lincolnshire

(By kind permission of the Commandant RAF College Cranwell)

When the decision was made to form the RAF, Trenchard was the man chosen to lead it. With his background, it can clearly be seen why. He understood the importance of co-ordination between land and air assets, particularly when carrying out offensive air operations, and he also realised the importance of morale; not only the morale of those under his command but the effect that air power could have on the morale of his enemy.

In January 1918, Trenchard was summoned back from France, knighted and appointed Chief of the Air Staff (CAS) on the newly formed Air Council. The days leading up to the official formation of the RAF were never going to be easy but following weeks of disagreements with Lord Rothermere, Trenchard resigned and returned to France. For the final few months of the war he commanded the newly formed Independent Force, a strategic bomber force made up of day and night squadrons that were tasked with striking at key targets without co-ordination with the other services.

Trenchard had been replaced as CAS by Major General Frederick Sykes but when Winston Churchill became Secretary of State for War and Air in 1919 he was reinstated as CAS. It was an appointment Trenchard would hold for the next eleven years. He worked tirelessly in the immediate aftermath of war to establish the RAF in time of peace and to secure its future by finding a permanent role for his new service. It was a sizeable task. The RAF was only budgeted to around 10 per cent of its wartime establishment, both in terms of squadrons and manpower, and so he had to fend off the other services to prevent the RAF from being absorbed back into the army and the Royal Navy.

With a new rank structure in place, Trenchard first became an air vice-marshal and then an air marshal, and in 1920 an opportunity came along for him to show the value of air power when he successfully argued that the RAF should take the lead to restore peace in Somaliland. Although a small air operation, its success allowed Trenchard to put forward his case for the RAF to police the British Empire and, soon after, the RAF was given control of British forces in Iraq while also policing India’s North-West Frontier.

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard. (AHB)

Meanwhile back home, Trenchard’s long-term vision for the RAF included the creation of its own institutions to develop an air force for the future and to engender an esprit de corps, and amongst his early successes were the founding of the RAF Cadet College at Cranwell, the Aircraft Apprentice scheme at Halton and the RAF Staff College at Andover. He was also quick to expand the RAF’s strength with the creation of the Auxiliary Air Force (a reserve force) and he also instigated the University Air Squadron (UAS) scheme with the first three UAS squadrons formed at Oxford, Cambridge and London.

Trenchard had succeeded in securing the RAF’s future. He became the first person to hold the rank of marshal of the Royal Air Force and continued as CAS until replaced by Sir John Salmond at the beginning of 1930. Trenchard was then created Baron of Wolfeton, entering the House of Lords as the RAF’s first peer. He always maintained a keen interest in military affairs and remained a strong supporter of the RAF for the rest of his life. Trenchard died in 1956 at the age of 83, but he had never forgotten the importance of Cranwell and so his family gave some of his personal belongings, including these boots, to the RAF College.

So much is owed to Trenchard’s vision and strength of character. Almost single-handedly he successfully fought off the seemingly endless attacks by the other services in order to keep the RAF in existence and to give it an enduring sense of pride that has lasted to this day.

3

RAF Roundel

THE RAF ROUNDEL is iconic and is known today all over the world. Essentially, the roundel has remained unchanged from its origins dating back to the early days of the First World War when the need to identify the nationality of an aircraft had first become apparent.

Early ideas of marking the nationality of an aircraft included painting the union flag but this proved unsatisfactory and so the RAF adopted a similar idea to the concentric circles used by the French. Although the colours of the union flag were maintained, the red, white and blue of the French markings were reversed so that the outer circle of the British marking was blue and its inner circle red. Initially the blue, white and red concentric circles of the British roundel were painted on the side of the fuselage, aft of the cockpit, and on the underside of the aircraft – as can clearly be seen on Object 4 – so that ground forces could clearly identify the aircraft’s nationality. But as the war progressed the circles were also painted on the upper surface of the top wing so that they could be seen during aerial engagements or if the aircraft was manoeuvring when close to the ground.

Affectionately known during its early days as ‘the target’, the RAF roundel has been modified over the years with...