![]()

‘THE SUFFRAGETTE OUTRAGE AT CHELTENHAM’

(Gloucester Journal, 27 December 1913)

‘ALSTONE LAWN SET ON FIRE. UNKNOWN WOMEN ARRESTED ON SUSPICION.’

Gloucestershire Echo, 22 December 1913

‘ARSON IN CHELTENHAM … UNKNOWN WOMEN ARRESTED ON SUSPICION.’

Cheltenham Chronicle, 27 December 1913

These headlines are of the kind which many associate with the struggle for women’s suffrage and they would appear to suggest that Cheltenham was in the grip of a wave of suffragette ‘terrorism’ which characterised the struggle elsewhere. This is wrong on two counts. Firstly, the incident at Alstone Lawn was an isolated one, perpetrated by outside itinerant fire-raisers. Secondly, the campaign for women’s suffrage included non-militant groups who were at least as important as the militants.

Nevertheless, headlines like this expressed the fear and outrage among many sections of society and were frequently articulated by the local and national press. So what actually happened and how was it reported?

In the early morning of Sunday, 21 December 1913, a fire was reported to the fire station in St James’ Square and to Cheltenham police. Alstone Lawn, a large but empty house in seven acres of grounds on the corner of Gloucester Road and Alstone Lane, was ablaze. The man who had seen flames darting from the roof was a gasworker, Edward Batson, who was cycling home to Alstone Croft from his job at the gasworks in Gloucester Road. He raced to the fire station in St James’ Square to raise the alarm. Such was the concern that both divisions of the brigade were ordered out and twenty men arrived to find the police already there. The house and grounds were surrounded by an eight-foot wall, some of which had an additional fence on the top and so they had to break into the stable yard and then into the house. The source of the fire was located in the wooden staircase which ran from the bottom to the top of the building. The hydrants were quickly employed, so the services of the engine were not needed and the fire was brought under control in half an hour. At 8.30 a.m., Fire Officer Such decided that the brigade could leave, though one man together with a number of police officers remained at the premises. A big hole had been made in the roof, damage was estimated at £300–400 and it was later decided that the house should be pulled down and the estate sold in small lots for further development.

What of the culprits? It was quickly established that the cause was arson, as a two-gallon oil can, still wet with paraffin, was found near the seat of the fire and it appeared that there were oil marks on the wallpaper nearby. A window to the conservatory on the ground floor was found open and, as the firemen and policemen had not used it, it was assumed that this was the method of entry. This theory was reinforced by the discovery of imprints of stockinged feet, one with a prominent large toe, on the floor of the same room. Suffrage literature was found in the grounds of the house. By 9.30 a.m., two women coming from the direction of Arle and the Cross Hands Inn were arrested in the Tewkesbury Road by Sergeant Welchman, whose suspicion was aroused by a strong smell of paraffin. It was also alleged that they had been seen by a policeman in the area of Alstone Lawn about half an hour before the fire was discovered. At the police station, paraffin was found on their stockings, boots and on the shorter woman’s cloak. Neither woman was prepared to give her name or address, they protested against ‘man-made laws’, began a hunger-and-thirst strike and were locked up.

Alstone Lawn, the magnificent though deserted house, set on fire in December 1913 by two suffragettes. (The Cheltenham Trust and Cheltenham Borough Council)

The Cheltenham firemen based at St James’ Square fire station, who dealt with the blaze at Alstone Lawn. (Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 6 December 1913)

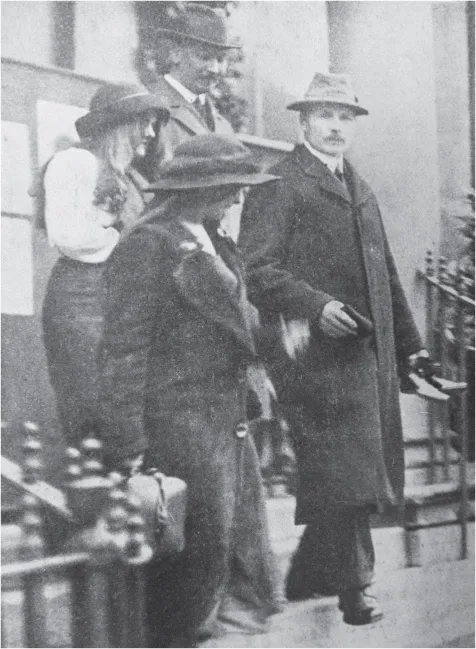

At the police court appearance on the Monday morning, the women were labelled ‘Red’ and ‘Black’. As well as the unusually good photograph we have of them coming out of the police station, we have the details circulated by the police:

When arrested, one of the women, whose age is 21 or 22, and who stands 5ft 1in or 5ft 2in., was wearing a navy blue skirt with white silk blouse, a dark grey rainproof coat, and a navy blue felt hat, with silk band. She was wearing a pair of black shoes, grey gloves, and a blue woollen scarf. This woman, who is well-built, has brown hair and blue eyes, and a full face.

The second prisoner is 23 years of age and about 5ft. 3in. in height. She has a small face, with brown hair and eyes. She is very slightly built, and has prominent teeth. When apprehended she was wearing a navy blue dress, with lace on the sleeves, a red ‘Teddy-bear’ cloth coat (with large black buttons, a turned-down collar, and a strap at the back), a red felt hat with fur band, a black veil, and sized four Derby shoes.

Both were therefore well-dressed in ‘respectable’ clothes and in no way were trying to avoid notice. Much was made of their appearance and demeanour in the press, the fact that they seemed to have been in high spirits when they arrived in court (‘they bounced into the box evidently in a very happy frame of mind with themselves’, CCGG 27/12/13), that both had their hair loose (not a sign of ‘respectability’) and with some comments on who was the better-looking. The tone was of mild wonderment and, at the same time, disapproval. The local press did not report what The Suffragette newspaper said – that the police had refused to allow them shoes, stockings or hairpins, the former because they were allegedly needed in evidence, as was the coat of one of them, the hairpins presumably as they could be used to self-harm or attack others.

Lilian Lenton and her accomplice Olive Wharry, coming out of Cheltenham Police Court after being found guilty of the fire at Alstone Lawn. (Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 27 December 1913)

One curious aspect of the case was that the charge which was made against them included the allegation that they intended to injure the owner of the property, Colonel B. de Sales la Terriere. This would not have held up in court if the case had been argued as the house had been empty since the death of the colonel’s mother in September 1911, the contents had been sold at auction in May 1912 and the whole estate had been unsuccessfully put up for sale. The fact that the surrounding boarding fence was described as dilapidated in places added to the impression that the property was deserted and it was a typical target for the suffragettes, who never sought to hurt people, only property.

The women refused to answer to the ‘male court’ and were therefore remanded in custody. They left the police court in a taxi to the Midland Station to catch the train to Worcester, where they were to be held in gaol. Again, the local press commented on their appearance as they left the court, both barefoot and with their hair loose, and also on the fact that they were greeted by at least two lady sympathisers, one of whom, ‘in a long brown coat’, followed them to the station and was allowed by the police escorts to chat freely to them. It was noted that at both the police station and the railway station they attempted to hide their faces from photographers. One senses continuing disapproval but perhaps grudging admiration for their resolute courage from the Gloucestershire Echo and the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, but the Gloucester Journal was less forgiving. It spoke of ‘dastardly’ acts, ‘nefarious work’ and ‘suffragette firebrands infesting the country’.

Throughout all the reporting, it was assumed that these women were suffragettes and certainly the evidence pointed in that direction. Apparently the fire chief had even sent one of the divisions back to the fire station when he had assessed the situation at Alstone Lawn, as fire brigades throughout the country had been warned always to leave some men on duty, it being believed that ‘when Suffragettes intend to make a big attack on property by fire they will probably create a small fire elsewhere as a ruse whereby to detract the attention of the firefighters.’ This was not the case here.

The two women, ‘Red’ and ‘Black’, were released from Worcester Gaol on 25 December under the terms of the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act of April 1913. Officially the Prisoners’ Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act, it had been passed by a jittery government to prevent there being a suffragette death on their hands at a time when hunger strikes by the women prisoners had become a political embarrassment. Prisoners suffering from ill-health because of hunger/thirst strikes could be released on licence until they had recovered sufficiently to be imprisoned again. ‘Red’ and ‘Black’ were supposed to reappear at Cheltenham on Monday, 29 December but proved to be elusive ‘mice’, who went into hiding and whom the government and police ‘cats’ could not catch.1

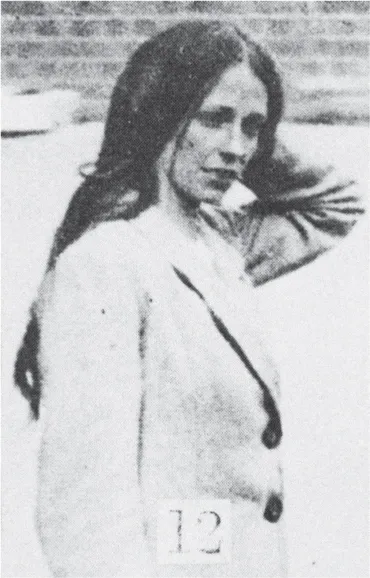

A Home Office surveillance photograph of arsonist Lilian Lenton in prison, probably June 1913, before her Cheltenham offence. (Wikipedia, public domain)

It was, however, reported that fingerprints had been obtained and that it should soon be possible to identify the culprits. This seems to have been a reasonable assumption as, after the passing of the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act, it had become more important for the police to be able to identify the ‘mice’ who had escaped or were evading recapture. Fingerprinting and covert photographing of prisoners were being developed and, in June 1913, when the young suffragette Lilian Lenton was in Armley Gaol (Leeds), a telegram was sent to the Home Office to ask whether, ‘in the Event of Liberation on Bail should photo and fingerprints be taken’ (Liddington: Rebel Girls, p.280). The prompt response was ‘Yes’, and this is the photo which was undoubtedly taken of Lilian Lenton and which was later one of a strip of photographs circulated to police forces by the Home Office. She was evidently one of the two culprits. On 9 May 1914, the Gloucester Journal reported that she had been arrested at Birkenhead and steps were being taken to bring her before the Cheltenham bench for the Alstone Lawn attack, but her continued pattern of arrest, hunger-striking, temporary release and further escape prevented this ever happening and she was still legally a ‘mouse’ when the war broke out.

Lilian Lenton was, effectively, a professional itinerant arsonist for the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) as the suffragette organisation was officially known. She was involved in a number of high-profile attacks on property, notably Kew Gardens tea house. It was her near-death from septic pneumonia caused by force-feeding in Holloway Prison in February 1913 that had helped propel the government to pass the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act. Some of the suffragettes undoubtedly embellished accounts of their activities in later years (and conversely some never spoke of them at all) but Lilian Lenton’s 1960 interview for the BBC proudly recalled that she had announced at WSPU headquarters in February 1913 that ‘I didn’t want to break more windows but that I did want to burn some buildings,’ so long as ‘it did not endanger human life other than our own’ (transcript, Museum of London, Suffragette Fellowship collection). She recalled that ‘my object was to burn two buildings a week’. What drew her to Cheltenham and Alstone Lawn cannot be known although her parents were living in Bristol at this stage, but she must somehow have acquired the knowledge of the empty property and one wonders whether this was via a very local informant.

Kew Gardens teahouse after the fire caused by Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry, February 1913. (Postcard, author’s collection)

It is likely that the other woman...