eBook - ePub

101 Things You Need to Know About Suffragettes

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

101 Things You Need to Know About Suffragettes

About this book

Suffragettes learned jiu-jitsu, repelled policemen with their hatpins, burnt down football stadiums and planted bombs. They rented a house near to Holloway Prison and sang rebel anthems to the Suffragettes inside. They barricaded themselves into their homes to repulse tax collectors. They arranged mass runs on Parliament. They had themselves posted to the Prime Minister, getting as far as the door of No. 10. Indomitable older members applied for gun licences to scare the government into thinking they were planning a revolution. Rebels. Warriors. Princesses. Prisoners. Pioneers. Here are 101 of the most extraordinary facts about Suffragettes that you need to know.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 101 Things You Need to Know About Suffragettes by Maggie Andrews,Janis Lomas,Professor Maggie Andrews,Dr Janis Lomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

IN VICTORIA GARDENS, IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOUSE of Commons, there is a statue of Emmeline Pankhurst. Many of us have heard about the role she and her three daughters – Christabel, Sylvia and Adela – played in winning the vote for women. The activities of the organisation they started, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), included smashing windows, burning postboxes, demonstrations in Parliament Square, being sent to prison and going on hunger strike.

This book will also show some of the other unexpected, ingenious and inventive activities that took place during their fifteen years of activism, and in a much longer fight for women’s political enfranchisement and equality. It was a struggle which involved many organisations, women and events, many less well known today than the Pankhursts remain. Before the Pankhurst family and the WSPU began the agitation for which they became famous, other groups of women had been asking, politely, for the right to vote. Their campaigns lasted almost 100 years, from the first women’s petition in 1832 until women finally achieved the vote (on equal terms to men, anyway) in 1928.

Householder women could actually vote locally and stand in local elections, and for school boards, prison boards and as Poor Law Guardians, from as early as the 1870s. As women’s rights activist Lydia Becker explained in 1896:

Political freedom begins for women, as it begins for men, with freedom in local government … There can be no training so excellent for women who may be called upon to vote in parliamentary elections, as the thoughtful and intelligent use of the municipal franchises which they already possess.

Women’s involvement in local politics often focused on housing, education, and social and infant welfare. For example, Emma Cons’ work as a rent collector gave her first-hand knowledge of the housing conditions of the poor, leading her to found the South London Dwellings Co. to provide affordable housing. In 1889 she became the first female Alderman on a London County Council, alongside Jane Cobden and Lady Sandhurst. She worked tirelessly for women’s suffrage, commenting wryly:

It is a bitter experience when one for the first time fully realises that even a long life spent in the service of one’s fellow citizens is powerless to blot out the disgrace and crime (in the eyes of the law) of having been born a woman.

However, women could not vote in County Council elections until 1907. Suffragette Elizabeth Garrett Anderson became the first female mayor when she was elected in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, in 1908.

Even as late as 1900, less than 60 per cent of the male population had a vote in Britain. The right to vote was based on property qualifications, which excluded many working-class men. In some of the poorer areas of the country, such as Glasgow, less than half the male population had the franchise. Many Labour Party politicians focused on campaigning to extend the franchise to everybody over the age of twenty-one, and formed the Adult Suffrage Society. The members were known as ‘Adultists’. Their president in 1906 was in fact a woman: Margaret Bondfield, a Trades Union campaigner and activist in the Shop Assistants’ Union. In January 1929, she was to become the first female Cabinet minister in British history.

Despite years of campaigning by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and other groups, there was little or no progress towards women’s enfranchisement. In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in Manchester. They developed innovative tactics to get the issue of women’s suffrage onto the front pages of the newspapers. A Daily Mail headline writer coined the word Suffragette in 1906, which was frequently, although not exclusively, used to refer to those who were prepared to break the law to pursue their cause. In the Edwardian era a multitude of suffrage groups emerged, including the Artists’ Suffrage League (1907), Actresses’ Franchise League (1908), the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, the Barmaids’ Political Defence League, the Gymnastic Teachers’ Suffrage Society and the Catholic Women’s Suffrage Society.

The first British dominion to give women the vote was the Isle of Man, which enfranchised women in 1881. The Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage congratulated the women electors of the Isle of Man on being the first women ‘within her Majesty’s dominions whose rights as parliamentary electors have been legally recognised’. As there were three seats in the House of Keys’ parliament and four male candidates, no woman stood for election. Nonetheless, the first person to cast their vote was a woman. In 1893, New Zealand became the first country to enfranchise women, followed by some states in Australia in 1902. Finland, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, USSR and Canada all enfranchised women before Great Britain. The first female MPs in the world were elected in Finland in 1907.

In 1909 the Liberal government introduced a suffrage bill proposing women’s suffrage for some women and the vote for virtually all men. The bill initially seemed to progress well but was dropped when an election was called. In the months that followed, Suffragettes’ anger at these broken promises led to a campaign that definitely deserved the name ‘deeds, not words’: window smashing began in earnest, alongside attacks on public buildings and services. This aggression was not one-sided: the establishment, and the policemen who enforced the status quo, often resorted to terrible violence in their efforts to suppress the women’s efforts to win the vote. On 18 November 1910, on what became known as Black Friday, a deputation of women attempted to reach the prime minister to protest about his failure to carry through a bill for women’s suffrage. The women were treated appallingly roughly: many were knocked to the ground, others kicked and trampled before they were able to get up. Plain-clothed policemen disguised as working men (and helped by some uniformed officers) carried out assaults on the women. Some of the assaults were of a sexual nature: women complained of hands being thrust up their skirts, and of having their breasts felt and squeezed; one woman described her breasts being wrung painfully, accompanied by the retort, ‘You’ve been wanting this for a long time, haven’t you?’ Being struck on their breasts was particularly distressing to women, as it was believed at the time to cause breast cancer. As another example, it was reported that Suffragette Mary Frances Earl had her ‘undergarments’ torn from her by a policeman; he used foul language as he attacked and proceeded to drag her up some steps by her hair. The bravery of the so-called ‘weaker sex’, who faced such horrors and nonetheless battled determinedly onwards, should never be forgotten.

Many other political groups used violence to articulate political frustration in this era too. Violence was nothing new to Edwardian political life. When Lloyd George endeavored to speak against the Boer War in Birmingham in 1901, for example, 350 policemen were drafted to protect him from the attentions of an estimated 30,000 protestors. The ensuing chaos led to two deaths, including that of a policeman, as well as forty hospital admissions. Campaigns using violence created anxiety within the Westminster establishment, but not all groups were treated the same way. Churchill initially refused to send in army troops to deal with the rioting miners in Tonypandy in 1910, in an attempt to avoid escalating the violence. British authorities were also worried that anarchist ideology from Europe would spread to Britain. They even surrounded one Swiss anarchist-turned-informant in hospital in Tottenham with armed guards. The papers reported fears that other anarchists would ‘attack the hospital, blow it up or destroy it with dynamite’ to silence him. Opposition to a parliamentary bill to introduce Home Rule in Ireland led, in 1912, to the formation of the Ulster Volunteers, and over 100,000 men joined Edward Carson in signing the Ulster Covenant, which bound its adherents to resist Home Rule for Ireland by ‘all means necessary’. Nonetheless, it seems that the violence enacted by the Suffragettes particularly appalled people, as it challenged deeply held ideas of femininity.

All was not sweetness and light in the Suffragette sisterhood itself either; even within the Pankhurst family, there were tensions. Not everyone in the movement agreed with Emmeline and her daughter Christabel’s leadership style, nor with their militant tactics. Consequently, a plethora of different suffrage organisations emerged in the run up to the First World War.

By 1912 militancy had escalated to unprecedented levels, moving from attempts to gain public sympathy to coercive tactics; the government responded harshly and public opinion began to turn even more firmly against the militants. Newspapers vilified the Suffragettes and advocated extreme punishments for them. The Derby Daily Express declared that every militant Suffragette should have their head shaved and be whipped with the cat-o’-nine tails. As the First World War approached, and violent protests grew, the WSPU began haemorrhaging members. With depleted funds, the WSPU appeared to be running out of steam. On the other hand, membership in the non-violent constitutional group the NUWSS grew during the same period; NUWSS branches expanded from thirty-three in 1907 to 478 by 1912. This growth may, however, have also been boosted by the publicity generated by the militants’ actions.

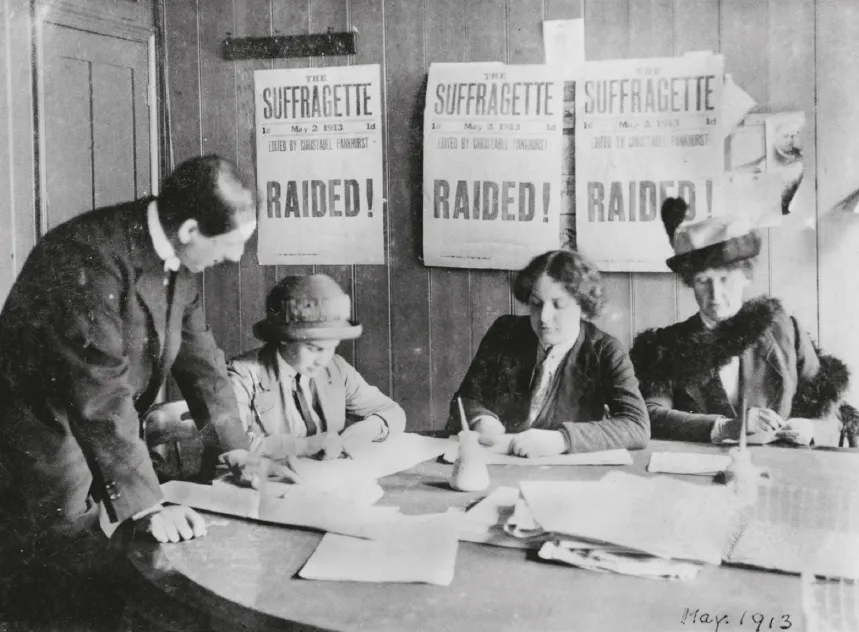

WSPU OFFICE IN 1913. (LSE, 7JCC/O/02/123)

By the end of the First World War in 1918, the Representation of the People Act, which gave some women the vote, was finally on the statute books. It extended the right to vote to about 6 million women aged thirty or over, as long as they met certain property qualifications – in their own right or through their husbands. Munitions workers, who had contributed so much to the war effort, did not generally meet these requirements. Neither did domestic servants. Many suffrage campaigners, including Lilian Lenton, were also indignant that, having suffered so much, they were still deemed too young to exercise a vote. Furthermore, the confusion around who actually had the right to vote was so great that many women who could vote did not. Consequently, the number of women who voted in the 1918 election was disappointingly low.

The struggle for political equality was not over either. It took another ten years for women to be enfranchised on the same terms as men. Nonetheless, in 1918 a victory party was held at the Queen’s Hall to celebrate. Blake’s poem ‘Jerusalem’, which had recently been set to music, was chosen as the new anthem for the women’s suffrage movement. Women continued to campaign for equal citizenship and suffrage supporters joined a range of new campaigning organisations. The Six Point Group sought legal, political, occupational, moral, social and economic equality for women. The Sexual Qualifications Removal Act in 1919 stated: ‘A person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post.’ For the first time, after its passing, women were able to become magistrates and sit on juries.

The continuing opposition to equal rights was led by prominent figures including the prime minister, Lloyd George. Despite this, in 1928 both Houses of Parliament passed the legislation for equal enfranchisement with an overwhelming majority, without objections and with the minimum of comment. Lord Birkenhead wound up the House of Lords’ debate by declaring, ‘My recommendation to your Lordships is to go into the Lobby in favour of this bill, if without enthusiasm, yet in a spirit of resolute resignation.’

Britain was at least ahead of many of its European neighbours: France did not enfranchise women until 1944, and in Switzerland women only gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971. (By contrast, in Saudi Arabia women were first allowed to vote in municipal elections in 2015.) However, it was still to take until 1970 for Equal Pay legislation to finally become law. Despite its passing, even today women earn less than men.

This book cannot cover all of the multifarious undertakings and experiences that make up the history of women’s fight for the suffrage, but hopefully it provides instead a starting point, for some, and for all a selection of shining examples of the bravery and determination of the women (and men) who fought to change the political landscape of Britain forever.

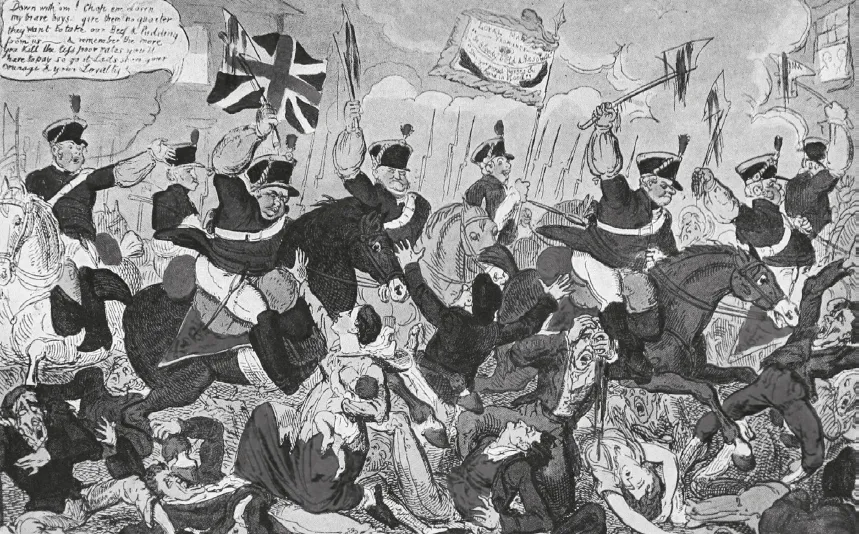

IN AUGUST 1819, THE RADICAL MP HENRY HUNT MADE his way to address a rally at St Peter’s Field, Manchester. Bands entertained the crowds, who were peacefully campaigning for parliamentary reform and an end to the system of ‘rotten boroughs’: sparsely populated regions which were represented by an MP (at great personal benefit to the incumbent) while huge industrial areas, such as Manchester, had hardly any.

Approximately 12 per cent of the 60,000- to 80,000-strong crowd were women. They included a group of suffrage campaigners from the textile mills known as the Manchester Female Reform Society (one of several such groups formed at that time). Dressed in white, the group was led out to the field by their president, Mary Fildes. The peaceful demonstration turned ugly when local magistrates ordered the arrest of Henry Hunt and the other organisers. Soldiers on horseback rode straight into the crowd, deliberately slashing at the densely packed protestors with their sabres (which had been sharpened before the event, to ensure maximum damage was inflicted). Seven men and four women died.

CONTEMPORARY PRINT OF THE PETERLOO MASSACRE. (CL/2018)

Mary Hayes, a pregnant mother of six, went into premature labour after she was ridden over by the cavalry. She later died. Margaret Downes’ death, meanwhile, was caused by a sabre wound. Another woman, Sarah Jones, a mother of seven, died after being beaten around the head with a special constable’s truncheon. Richard Carlile, due to address the crowds that day, stated that women were deliberately targeted. The president of the group of mill girls was amongst them: as an eyewitness later described, ‘Mrs Fildes was hanging, suspended by a nail on the platform of the carriage, caught by her white dress. She was slashed across her exposed body by an officer of the cavalry.’ Mary Fildes, however, recovered from her injuries and continued to campaign for women’s suffrage into the 1830s and 1840s.

HENRY HUNT (THE MP IN THE PREVIOUS ITEM) PUT forward a bill, proposed by Mary Smith from Yorkshire, specifying that every unmarried female who met a property qualification should be given the vote.

When MPs agreed the wording of the so-called ‘Great Reform Act’ of 1832, the legislation referred to ‘male persons’ rather than ‘persons’, explicitly excluding women from voting for the first time in British history. The Act increased the suffrage from ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Female Suffrage Campaigners Were Killed at the Peterloo Massacre

- Women Were Not Technically Barred from Voting Until 1832

- The First Ever Women’s Suffrage Committee was Inspired by a Walking Tour

- Some Women Actually Voted as Early as 1867

- Mrs Fawcett Became a Suffrage Campaigner after she was Robbed

- Millicent Garrett Fawcett Led the Investigation into Boer Concentration Camps

- One of the First Bills for Women’s Suffrage was Written by Emmeline Pankhurst’s Husband

- The Suffragettes Began their Fight in Manchester

- Suffragettes Sold their Jewellery to Raise Funds

- Emmeline Pankhurst Starred in a Movie

- Christabel Pankhurst was Arrested Outside a Talk by Winston Churchill

- Winston Churchill was Nearly Killed by Suffragettes at a Railway Station

- Two Suffragettes had Themselves Posted to the Prime Minister

- Suffragettes Invaded Parliament more than Eighty Times

- Suffragettes Produced a Cook Book

- Suffrage Rallies Were Picketed by the Anti-Suffragists

- Suffragettes Barricaded Themselves into Houses to Avoid Paying Tax

- University Graduates Petitioned for the Right to Vote on the Grounds of Intelligence

- Suffragettes Were Often Temperance Campaigners Too

- ‘Baby’ Suffragettes Were as Young as Eleven

- Suffragettes Were Leaders in the Animal-Rights Movement

- Suffragettes Had Their Own Board Games

- The Magazine Votes for Women was Sold in Whsmith

- Many Suffragettes were Concerned about their Appearance

- Suffragettes once Whitewashed a Horse for a Pageant

- Suffragettes put Padding Under Their Clothes to Protect Themselves from Police Brutality

- Suffragette Vehicles Included a Protest Caravan

- The First Female Chauffeur in Britain was a Suffragette

- The WSPU had their Own Chain of Shops

- Some Suffragettes were Graffiti Artists

- Emmeline Pankhurst is Rumoured to have had Lesbian Affairs

- The First Woman to Marry without Promising to Obey was a Suffragette

- Some MPS Claimed Women did not want the Vote

- Suffragettes Used Acid in their Attacks

- Men Stood for Parliament as Suffrage Candidates

- One Suffragette Leader Started her Career as a Romantic Novelist

- Suffragette Property Seized by the Police Included Royal Diamonds

- Gandhi Supported Votes for Women

- Suffragettes Made Mass Runs on Parliament

- Emily Wilding Davison was not the First woman to Die for the Cause

- Suffragettes Staged Sex-Strike Comedies and other Feminist Theatre

- Not all Suffragettes were Able-Bodied

- Suffragettes Boycotted the 1911 Census

- The WSPU were Banned from the Royal Albert Hall

- Many Suffragettes were Keen Cyclists

- Suffragettes had their own Medals

- Suffragette ‘Crimes’ Included Failing to License a Dead Dog

- Suffragettes Rented the House Behind Holloway Prison

- Suffragette Prisoners had no Underwear

- Some Husbands paid Suffragettes’ Fines so they could come Home and do the Housework

- The Prison Force-Feeding teams were Led by Doctors

- Suffragette Prisoners Pretended to be Vegetarian

- Emily Wilding Davison Kept Prison Force-Feeders at bay Using a Hairbrush

- Upper-Class Suffragettes Received Better Treatment

- The WSPU Ran Nursing Homes for Recovering Suffragettes

- The First Prisoner to be Released Under the Cat and Mouse Act was a Man

- Some Women were Force-Fed Hundreds of Times

- The WSPU was Unpopular in Wales

- Suffragettes went on mass Window-Breaking Excursions

- The Suffragettes Held Global Conferences

- Queen Victoria was against Women’s Suffrage

- Emmeline Pankhurst Dubbed Women who Opposed her ‘Traitors’

- An Effigy of a Suffragette was Burned on Bonfire Night

- The First Suffragettes were Labour Supporters

- The Suffragettes had a Patron Saint

- Christabel Pankhurst Lived with a French Princess in Paris

- One of Mrs Pankhurst’s Daughters moved to Australia

- Even Suffrage Supporters Sometimes Objected to WSPU Tactics

- Suffragettes Once Threw a Hatchet at the Prime Minister

- The Suffragettes Promoted Male Abstinence

- A Suffragette Attacked the crown jewels

- Sylvia Pankhurst led a Delegation to Downing Street

- Suffragettes Had Guns

- Suffragettes were Prolific Arsonists

- Suffragettes Sometimes Carried out Revenge Attacks

- Women used Ingenious Disguises to Avoid Being Arrested

- Suffragettes Targeted Sporting Venues

- Suffragette Activities Affected the Stock Exchange

- Suffragette Weapons Included Hatpins, Sticks and Umbrellas

- There was an Empty Carriage at Emily Wilding Davison’s Funeral

- Suffragettes Used Jiu-Jitsu

- Suffragettes were Secretly Photographed in Prison

- Suffragettes were Drugged in Prison

- The Woman who Attacked the Rokeby venus was known as ‘Slasher Mary’

- The WSPU Suspended their Campaign for Suffrage to help win the First World War

- Some Suffragettes took an Active Role in the First World War

- English and German Suffragettes met at a Peace Conference in 1915

- Emmeline Pankhurst Adopted war Babies

- Suffragettes Ran a toy factory

- Suffragettes Ran a War Hospital in Serbia

- A Suffragette was accused of trying to poison the prime minister

- Some of the First Female Police Officers were Suffragettes

- Christabel Pankhurst Stood as an MP for her own political party

- The First Women Elected as an MP was in Prison when she Won

- Some Suffragettes Became Fascists

- Many Suffragettes Carried Campaign Scars for the Rest of their lives

- The Women’s Institute Founders Included Suffragettes

- Sylvia Pankhurst Died in Ethiopia

- A Special car was produced to Celebrate the Suffragettes

- The First Englishwoman to become an MP Opposed Austerity

- ‘Every Woman is a Chancellor of the Exchequer’

- Further Reading