![]()

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail.

– Winston Churchill, 4 June 1940

The Beginnings

The campaign to liberate Europe can be traced back to June 1940, and the period when Britain, its Empire, and Dominions stood alone. For the next four years the Western Front was defined by the Channel and North Sea, which offered no scope for other than anti-aircraft or coastal artillery units to see action. However, individual Gunners played a significant role in the events that led to D-Day and the Normandy campaign.

With seventy years of hindsight, the success of Operation Overlord may appear inevitable. Yet it was very a risky operation. The English Channel is a formidable obstacle. Some of the most powerful armies of all time have baulked at making an opposed Channel crossing. Throughout British military history, British expeditionary forces typically entered the continent through friendly ports. British expeditions to an occupied shore usually failed dismally, as at La Rochelle, Saint-Malo, Walcheren and Bergen op Zoom in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The twentieth-century experiences of Gallipoli, Dar es Salaam and Diego Suarez (now Antsiranana) were hardly encouraging. The development of the plans that lead to the success of Operation Overlord were in the hands of two senior gunner officers. General Sir Alan Brooke (the future Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke), as the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), was Churchill’s senior military advisor and shaped the timing and command of D-Day. Lieutenant General F.E. Morgan, as the Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (Designate) (COSSAC), would play a key role in determining that D-Day would take place in Normandy, and the plans for this most complex and successful operation.

Winston Churchill, the embodiment of British national spirit and bloody mindedness, was determined that British troops should strike back at the Germans. On 4 June 1940, the day after the last British soldier left Dunkirk, Churchill sent a memo instructing the Defence Secretary to the War Cabinet thus: ‘It is of the highest consequence to keep the largest numbers of German forces all along the coasts of the countries they have conquered, and we should immediately set to work to organise raiding forces on these coasts.’ Ten days later, Chiefs of Staff created the post of ‘Commander of Raiding Operations on Coasts in Enemy Occupation, and Adviser to the Chiefs of Staff on Combined Operations’. This post headed an organisation that would ultimately become Combined Operations, headed by Sir Roger Keyes and then Lord Mountbatten. The raids on the coast of Europe had a profound impact on the Germans and resulted in their maldeployment in 1944.

Commando Gunners

On the evening of 23 June 1940, soldiers from No. 11 Independent Company, a volunteer force raised for the Norway Campaign, carried out Operation Collar, a raid on the coast between Boulogne and Le Touquet, which killed two German soldiers. The only British casualty was Lieutenant Colonel D.W. Clarke RA, whose ear was grazed by a bullet. Clarke, an observer on the raid, was military assistant to Sir John Dill, the Vice Chief of the Imperial General Staff (VCIGS). In May 1940, following the evacuation from Dunkirk, he had submitted a proposal to General Dill for small raiding units, called commandos, inspired by childhood recollections of similar Boer forces.

During the winter of 1940–41 Combined Operations developed commando and other raiding forces. Although little of this activity would require artillery, many gunners joined the commandos. One of the most influential was Captain J. Durnford-Slater, who volunteered to join a ‘raiding force’ in June 1940, while adjutant of 23rd anti-aircraft (AA) and Heavy Training Regiment. Promoted to brevet lieutenant colonel, he raised the first Army Commando unit, No. 3 Commando, in June 1940. He led this unit on its first raid on Guernsey in July 1940, Operation Ambassador, and would be the Deputy Commander of Commandos on D-Day. Captain G.H. March-Phillipps was another gunner officer who raised a commando force from volunteers. As a major, he commanded Small-Scale Raiding Force, or No. 62 Commando, initially in support of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the secret service, and later responsible for raiding the Channel coast, resulting in the award of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). This small organisation carried out some spectacular operations out of proportion to its size and would become part of the Special Air Service.

Rebuilding an Expeditionary Force

The offensive raids across the Channel were only a minor activity of the Army and the Royal Artillery in 1940. The main task of the Army was to defend the British Isles from attack. After Dunkirk, Home Forces had been rearmed and equipped to repel the expected German invasion. During 1941, Home Forces, which was Brooke’s command, practised mobile operations against an invader. At the same time, the Army tried to apply the lessons that had emerged from the debacle in France and from other fronts. Some of these had significant implications for the Royal Artillery. The story of the RA over this time is covered in the companion volume The Years of Defeat: 1939–41. From 1942 the Home Army would be the basis for expeditionary forces. The training and doctrine would be under the direction of the Major General Royal Artillery (MGRA), Home Forces Major General O.M. Lund.

After Dunkirk, there was much soul-searching about the reasons for German success. One obvious conclusion was that to face an armoured enemy supported by aircraft, a higher proportion of anti-tank and anti-aircraft gunners would be needed. Infantry divisions received a light anti-aircraft (LAA) regiment and a divisional anti-tank regiment, while each corps would have a corps anti-tank regiment and LAA regiment. The Bartholomew Commission challenged whether the division was too large a formation to operate in mobile warfare. There were calls to restructure formations around all-arms brigade or even battalion groups. These structures were tried in the Western Desert during 1941–42 and the Gunner side of this story is told in other volumes of this history. With this came pressure to devolve command of artillery to brigades and dispense with artillery commanders at divisional and corps level. These were argued to be cumbersome and unresponsive relics of positional warfare of 1914–18, and irrelevant to the mechanised warfare faced in 1940.

The rise of Lieutenant General B.L. Montgomery, initially of 5th Corps and then South East Command, under the patronage of Brooke, was key to restoring the divisional and corps levels of command. He led the development of the tactical methods that characterised the British Army in the second half of the war and become known as ‘Montgomery’s Colossal Cracks’. Montgomery emphasised fighting battles using the co-ordination of all arms at a divisional level, using artillery centralised at the highest level.

This would not have been as easy had not techniques been developed harnessing wireless communications to control the fire of many batteries of guns. These were initially demonstrated by Brigadier H.J. Parham, as Commander Royal Artillery (CRA) of 38th Division, but based on his experience in the 1940 campaign as CO 9th Field Regiment. His initial demonstration took place in 1941 and was followed by demonstrations in spring 1942. There were flaws in the methods used to calculate corrections, which resulted in rounds falling among VIP spectators. However, the audience was sufficiently impressed, not least with the speed with which the offending batteries were stopped, and the techniques, after modification by the Royal School of Artillery (RSA), were adopted and became those used across the field artillery.

German successes also highlighted the value of close air support to land operations. The story of the development of close air support by the Allied air forces lies mainly outside the scope of this history. One key tactical role of aircraft was for artillery reconnaissance and artillery observation. The RAF–Army co-operation squadrons had suffered heavy losses in France in the face of German fighter aircraft and anti-aircraft guns. Furthermore, while the Home Army was not in contact with the enemy, the RAF was, and army co-operation became a low priority for the service. The development of Air Observation Posts (air OP) with artillery officer pilots started in 1940, initially by Captain H.C. Bazeley, and championed by Brigadier Parham, a pilot himself. The logic was that it was easier to train an artillery officer to fly than train an RAF pilot to understand the tactical situation. This development was not wholly welcomed or supported by the RAF, but the Operation Torch expeditionary force to North Africa in November 1942 was accompanied by an experimental air OP Flight, with Gunner pilots flying aircraft provided and maintained by the RAF. The demonstrable success resulted in the adoption of air OPs across the Army. Besides the air OP squadrons, there was development of joint procedures for RAF and artillery co-operation, including the adoption of common methods for spotting the fall of shot and applying corrections.

With the entry of the USA into the war the priority for the Home Army changed from defeating an invasion to forming an expeditionary force. The evolution of Allied strategy towards North Africa and Sicily resulted in the departure of two corps and six divisions for the Mediterranean theatre.

Unusually, the British Army could prepare for its major campaign from home soil. The Gunners could draw on resources of the RSA, whose role is covered in more detail in Chapter 3. General Lund, MGRA Home Forces, instigated six-monthly Gunner conferences at Larkhill, attended by all available senior officers. The agenda for these covered any matter of interest to the gunners from the deployment of artillery to support a corps to the design of shoulder titles. These conferences, along with Royal Artillery Notes (RA Notes), provided a mechanism for promulgating consistent policies and procedures. The old cliché ‘ten gunners and eleven opinions’ was put to rest. This would become important when artillery needed to be regrouped frequently and operate with consistent procedures.

The defence batteries formed to support local defenders against invasion were converted to field artillery or transferred to the coastal artillery. An expeditionary role was considered for the batteries of super heavy rail guns deployed in the south-east. This was later abandoned as heavy bombers took on the roles envisaged for long-range heavy artillery. The 11th Survey Regiment, established to locate German cross-Channel artillery through flash spotting and sound ranging, eventually became a key organisation, plotting the launch of the V1 and V2 weapons.

Throughout 1942–43 the Army continued to experiment with its divisional organisation, based on the results from formation exercises and reports from overseas. Armoured divisions were initially very tank-heavy, with two armoured brigades, each of three armoured regiments and divisional ‘support group’ with a single infantry battalion and a regiment each of field and mixed anti-tank and LAA artillery. By 1944 the armoured division was formed of a more balanced force of four armoured regiments (one of which was designated armoured reconnaissance) and four infantry battalions, one of which was mounted on armoured carriers and half-tracks. These were organised into two brigades and supported by four artillery regiments (two field, one anti-tank and one LAA). In 1942–43 mixed divisions were formed each of two infantry brigades, each of three battalions and one armoured brigade of three regiments. However, this was dropped in favour of infantry divisions of nine-battalion infantry divisions supported by independent armoured and tank brigades. Training exercises and the experience from North Africa had shown that both armoured and infantry formations needed a higher proportion of infantry. One consequence of the reorganisation was the disbandment of the 42nd Armoured Division, and re-equipment of the 79th Armoured Division with armoured engineer vehicles left several artillery units surplus. These included the 53rd and 55th Anti-Tank Regiments, 142nd, 147th, 150th and 191st Field Regiments and the 93rd and 119th LAA Regiments.

During 1943 those units of Home Forces units destined to join the 21st Army Group were identified. The MGRA Home Forces, Major General O. Lund, became MGRA 21st Army Group, while Brigadier J.R. Barry became Brigadier Royal Artillery (BRA) Home Forces for those artillery units not assigned an expeditionary role. Those that remained were used to run the transit and holding camps in the UK. Rolls of individual officers were maintained by RA 21st Army Group as replacements and a policy agreed that vacant posts within 21st Army Group would be filled from this list, rather than internal promotion.

Eventually the remaining units in Home Forces were depleted by drafts for gunner and infantry units in 21st Army Group. Units that had once been in the forefront of the expected battle of the beaches of Britain developed into holding and training units with regret, for the general good, which deserved the highest praise. The 6th Regiment Royal Horse Artillery (RHA), 171st (Dorset Yeomanry) Field Regiment and 92nd (Gordons) Anti-Tank Regiment, to mention a few, would have no battle honours for this war, but they helped to win it as surely as others that may have fought from the Nile to the Baltic.

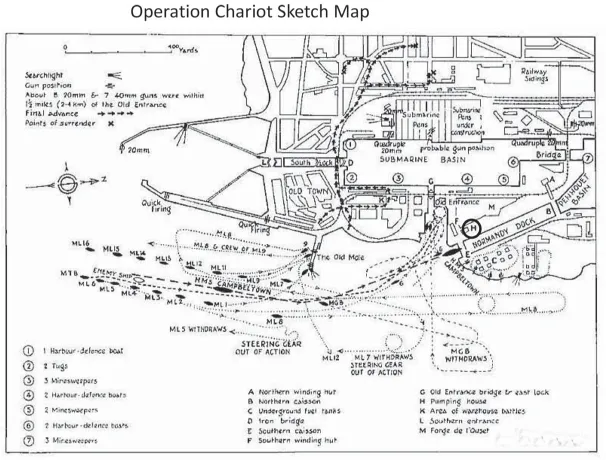

Saint-Nazaire: Operation Chariot

After the armistice was signed with the French on 23 June 1940, the Germans retained control of northern France and the Atlantic coast. The north coast was important as a base for air operations against Britain and any invasion. One of the objectives of the German invasion of France in 1940 had been to occupy its Atlantic coast to wage submarine warfare against Britain. The ports of Brest, Lorient, Saint-Nazaire and the Gironde estuary became submarine bases, with concrete submarine pens built to protect U-boats from air attack.

Selection of Operations Planned or Executed 1942–44

1 Chariot. Raid on Saint-Nazaire, 28 March 1942.

2 Rutter/Jubilee. Raid on Dieppe, 19 August 1942.

3 Sledgehammer. Proposed cross-channel operation, mid-1942.

4 Torch. Invasion of North Africa, November 1942.

5 Husky. Invasion of Sicily, July 1943.

6 Round-up. Proposed cross-Channel operation, 1943.

7 Rankin. Planned operation in the event of German collapse, 1943.

8 Starkey. Feint across Dover straits, September 1943.

9 Overlord. Cross-channel operation, June 1944.

10 Jupiter. Alternative to Overlord proposed by Churchill in the event of compromise.

11 Fortitude North. Deception plan to threaten attack on Norway, 1944.

12 Fortitude South. Deception plan to threaten attack on Pas-de-Calais, summer 1944.

13 Anvil/Dragoon. Invasion of southern France planned to be simultaneous with Overlord, but postponed to August 1944.

14 Bolero. Build-up of US forces in the UK.

On 14 December 1941, one week after the entry of the US into the war, Hitler ordered the construction of a new West Wall covering the Atlantic coast. On 23 March 1942, Hitler Directive No. 40 expanded on the command of coastal defence. This directive emphasised the danger of landings, gave the highest priority to naval installations and urged vigilance. Later the same week, on 28 March 1942, a British Combined Operations raid, Operation Chariot, demonstrated German vulnerability by sailing into the port of Saint-Nazaire and destroying the docks. These included the only dry dock capable of accommodating the German battleship Tirpitz on the Bay of Biscay. Its destruction would make it difficult for the Tirpitz to carry out commerce raids.

Lance Sergeant Arthur Dockerill from Ely in Cambr...