eBook - ePub

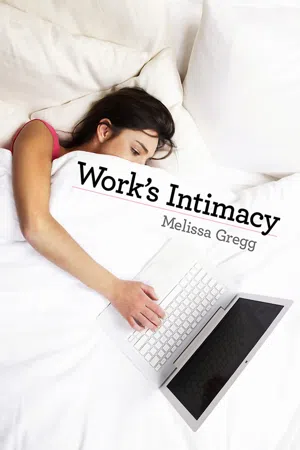

Work's Intimacy

About this book

This book provides a long-overdue account of online technology and its impact on the work and lifestyles of professional employees. It moves between the offices and homes of workers in the knew "knowledge" economy to provide intimate insight into the personal, family, and wider social tensions emerging in today's rapidly changing work environment.

Drawing on her extensive research, Gregg shows that new media technologies encourage and exacerbate an older tendency among salaried professionals to put work at the heart of daily concerns, often at the expense of other sources of intimacy and fulfillment. New media technologies from mobile phones to laptops and tablet computers, have been marketed as devices that give us the freedom to work where we want, when we want, but little attention has been paid to the consequences of this shift, which has seen work move out of the office and into cafés, trains, living rooms, dining rooms, and bedrooms. This professional "presence bleed" leads to work concerns impinging on the personal lives of employees in new and unforseen ways.

This groundbreaking book explores how aspiring and established professionals each try to cope with the unprecedented intimacy of technologically-mediated work, and how its seductions seem poised to triumph over the few remaining relationships that may stand in its way.

Drawing on her extensive research, Gregg shows that new media technologies encourage and exacerbate an older tendency among salaried professionals to put work at the heart of daily concerns, often at the expense of other sources of intimacy and fulfillment. New media technologies from mobile phones to laptops and tablet computers, have been marketed as devices that give us the freedom to work where we want, when we want, but little attention has been paid to the consequences of this shift, which has seen work move out of the office and into cafés, trains, living rooms, dining rooms, and bedrooms. This professional "presence bleed" leads to work concerns impinging on the personal lives of employees in new and unforseen ways.

This groundbreaking book explores how aspiring and established professionals each try to cope with the unprecedented intimacy of technologically-mediated work, and how its seductions seem poised to triumph over the few remaining relationships that may stand in its way.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I: The Connectivity Imperative: Business Responses to New Media

1

Selling the Flexible Workplace

The Creative Economy and New Media Fetishism

The lifestyle city

As the Australian summer drew to a close in March 2009 it was becoming possible to think that Queensland had finally shrugged the perceptions of provincialism that had been its historical destiny. This was the month that Anna Bligh became the first female in history to be elected Premier of an Australian state, just six months after another woman from Queensland, Quentin Bryce, was sworn in as the nation’s first female Governor General. A year earlier, a Queenslander was elected to the office of Prime Minister and he appointed an old schoolmate Federal Treasurer. For a region often lampooned for its backward image and lack of relevance to the rest of the country, something significant was brewing in the North.

Beyond political markers, by 2009 the Queensland Government’s “Smart State” policy, a platform designed to invest large sums of money to enhance the cultural and intellectual infrastructure of its capital, Brisbane, had also proven their purpose. A major renovation of the State Library and the construction of a new Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) – both facing the picturesque river stretching through the center of the city – were the centerpiece of a newly revitalized arts and information precinct. The installation of a revolving tourist “eye,” in the vein of London’s signature riverside attraction, seemed to confirm the transformation of Brisbane’s South Bank from its original function as World Expo site in 1988 to a national forum for cutting-edge arts and culture.

To this point, Brisbane had marketed itself as “the lifestyle city.” Long-serving Labor Party Premier Peter Beattie (1998–2007) had seized every opportunity to brand his home town as part of the beaming, folksy image he projected to the media and interstate investors. By the middle of the decade, the slogan had been replaced with a “creative city” tag.1 The transformations taking place in Brisbane seemed to confirm the lucrative profits of these concerted exercises in spin. A new “Green Bridge” stretching across the river south of the CBD had cut commuter traffic across major arterials, with a growing number of cycle paths and walking routes taking advantage of Brisbane’s subtropical climate. Heading north, real estate developments around Breakfast Creek and Bowen Hills were bordered by bunting. Vast tracts of newly released commercial land promised to deliver a cosmopolitan playground for local office workers, complete with cocktail bars and boutique cinemas by the water. A new Mayor, Liberal Party candidate Campbell Newman, embarked on an ambitious system of underground tunnels to ease transport congestion. Meanwhile, plans for a footbridge linking north and south of the CBD were a striking testimony to the city’s onward advance.

The combined impact of this major construction program tested the patience of long-time residents, already concerned at the influx of migrants to the city. In response, the local council launched a strategic billboard campaign to soothe citizen anxieties. “Living in Brisbane 2026” was a policy affirmation of the optimism required for the city’s future, particularly since a history of political corruption had severely damaged its sense of pride in the past.2 Brisbane Marketing Chief John Aitken explained: “We want to be a clean, green, and sustainable city. We’re looking globally at where our future lies.” But newspaper articles covering this transformation were quick to note that “for a city that still prides itself on cockroach races on Australia Day, Brisbane’s road to Damascus experience may still be a work in progress.”3

Of all these developments, one of the most notable was the opening of the Creative Industries Precinct at the Kelvin Grove campus of the Queensland University of Technology. Offering an array of training and study opportunities for locals who might imagine working in the very cultural sectors that policymakers now sought to promote, the CI complex remains a striking manifestation of government investment priorities of the period. To build the campus, a whole suburb was transformed from a mix of residential housing and disused army land to performance theaters, lecture space, and fashion studios. A social inclusion agenda also ensured housing commission beneficiaries mixed with students in the delis, cafes, and supermarkets constituting a new “urban village” (Klaebe 2006). Holding his trophy for Most Outstanding Actor at Australia’s annual television awards in May 2009, Underbelly star Gyton Grantley made a point of thanking QUT for the training vital to his success. In one small gesture, the creative industries brand had taken center stage, and QUT’s contribution to national culture was hard to ignore. With southern states facing major fallout from the financial crisis, Brisbane had become a genuine contender to rival Sydney and Melbourne as Australia’s ideal creative city.

A year later, the picture had vastly changed. Premier Bligh’s authority had all but vanished following a plan to sell off key state-owned assets in an effort to remain solvent amidst the financial crisis. Major construction projects and real estate developments in and around the CBD were suspended pending ongoing investment support. The business press lamented the declining number of cranes on Brisbane’s skyline, a colloquial signifier of industry downturn. The Brisbane boom was brief and potent. Its effects barely had a chance to reach the many workers who moved cities during the decade in anticipation of its spoils.4 In the rush to embrace the benefits of the new knowledge economy, this chapter shares lessons from a period when hopes for a better future were pitched on instrumental exercises in city branding. This is because, far from being a peripheral experience of work life in the knowledge economy, Brisbane remains a template for initiatives in creative cities policy development taking place on a global scale. The success of its creative industries education strategy continues to influence the study and career options of local and international students alike, just as the research arm of the QUT CI precinct – home of the larger, multi-stakeholder ARC Centre for Creativity and Innovation – plays a key role in shaping international debate (e.g., Flew and Cunningham 2010; Keane 2007). Beyond the boosterism of boardroom discourse, this chapter sheds light on the human effects of one city’s changing economic fortunes, to set the scene for the more intimate stories that follow in the rest of the book.

The Smart State

A unique convergence of financial, academic, and political interests contributed to Brisbane’s branding as the “Smart State.”5 Building on the transformation of Queensland’s Gold Coast into a home for film and television production outsourced from the US (Ward and O’Regan, 2007), Brisbane’s status as creative city is one of the clearest examples available of state-sanctioned investment in cultural labor. This local venture is, however, part of a larger story unfolding in the wake of Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class (2002) and its warm reception in policymaking circles. The message many distilled from Florida’s book was that artistic and symbolic workers were a proven tonic to enhance quality of life, levels of tolerance, and cultural diversity in urban areas.

Cities across the globe have since engaged a range of efforts to design areas compelling enough to attract these talented – and typically wealthy – workers (Oakley 2004). A suite of criticisms that emerged against Florida’s theory and methods (e.g., Lovink and Rossiter 2007; Banks 2009) failed to dampen the enthusiasm of politicians and business investors seeking solutions to the urban decay and social anomie attending the shift to post-industrial economies. Creative industries policies were central to the revitalization of UK cities under the broader “Cool Britannia” framework, and the model continues to offer compelling visions of economic prosperity in cultures and countries with greatly different administrative arrangements (Pratt 2009; Potts and Cunningham 2008).

For Brisbane in particular, the Smart State strategy and creative industries policy direction were opportunities to reimagine the city in the wake of the repressive regime of former Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen. Throughout the 1970s, Queensland’s unique system of political representation had allowed a powerful bloc of country voters to exert disproportionate influence on elections and maintain the conservative National Party in power. With only a single House of Parliament and hence few structures for legislative scrutiny, the government had been able to pursue a campaign of surveillance and intimidation against young people in the city, targeting activists and artists especially. Specific laws allowed police to disperse social gatherings without cause, which made protests of any kind illegal, and had the latent effect of preventing the development of independent music and cultural events. Notorious moonlight patrols ramped up the already heavy-handed policing of alternative lifestyles and modes of dress in daylight hours (Morrison 2007; Stafford 2006).

Against this backdrop, Brisbane needed a major exercise in rebranding to overcome perceptions that had been memorialized by Unkle Fats and the Parameters in the punk anthem: “Pig City.”6 The many residents who had left the state in fear during previous decades needed reassurance that they could return to a safe and supportive home town, just as interstate migrants needed strong evidence that the city’s attitudes had changed. In this sense, Brisbane fits Andrew Ross’s observation that “an element of desperation” accompanies the creative industries trend in cities seeking a competitive advantage in globalized markets (2008: 33). On the surface, such policies seem designed to cater for workers at the heart of the economy being promoted. In effect, however, sustainable work models are less of a focus for attention than the boosts to real estate value in boutique areas flourishing near creative “hubs.” In Brisbane’s flagship newspaper, The Courier-Mail, feature stories at the time contributed to the prospect of an economic boom by touting the city’s affordances as a “head office heaven.”7 These PR pieces appearing in business and employment lift-outs highlighted the desirable rates for commercial space in comparison with other cities, as tax incentives from the state government attempted to woo firms from elsewhere.8 Since their audience was generally local, such features played a key role in maintaining morale for those business owners and CEOs who had already made the decision to “head north.” Yet their interests were clearly pitched around the company bottom line. The workers employed in the burgeoning knowledge and service economy were of comparably little concern.

Figure 1.1 Selling the Brisbane Boom: a cover page from the Courier Mail’s weekly careers lift-out halfway through the study; Within a few months the financial crisis was threatening hundreds of jobs © Newspix / Kevin Bull

The Brisbane boom

Brisbane’s changing demographics were soon evident in the growing number of luxury apartments taking position along the waterfront. In inner-city suburbs like New Farm, old boarding hostels and iconic “Queenslander” ranch houses were sold off in their dozens for more profitable multi-occupier arrangements. An old electricity substation adjacent to the transformed Powerhouse Centre for Performing Arts – itself a redeployment of an actual power-generator plant from an earlier industrial era – was just one of many high-end property redevelopments conceived and completed in the years of this study. With its sweeping riverfront park and fortnightly Farmers’ Market, New Farm was an optimal location both for Baby Boomers seeking a lifestyle change and youngsters from more expensive cities harboring hopes of a waterside address. In the nearby enclave of Teneriffe, exclusive homeware stores opened to cater for the surfeit of loft-style apartments available in disused shipping warehouses. This classic post-industrial gentrification process capitalized on decommissioned freight districts in picturesque areas, turning the workplaces of an old economy into the domestic leisure space of the new. Extra bus services were needed to service the influx of residents commuting to the city for work, while online start-ups, media broadcasters, design and fashion businesses offered more conveniently located employment for the city’s nouveau riche. A steady rise in cafes and bars fueled the consumption habits of this cash-rich but time-poor professional clientele.

The jewel in the crown of Brisbane’s transformation from “sleepy little town” to “funky urban district” was the makeover of Fortitude Valley.9 Once a late-night haven for queers, punks, and misfits (not to mention the corrupt cops of the city’s recent past), collaborations between the local city council and Creative Industries researchers provided economic modeling and research data to demonstrate the area’s viability of as a “Special Entertainment Precinct” (Flew et al. 2001). Fortitude Valley was the first nightclub zone in the country to be accorded this status in July 2006. Existing residents protesting the development were met with well-funded billboard campaigns emphasizing the district’s new slogan: “Loud and Proud.” A host of measures, including special street signs, speed restrictions, and police patrols, took effect in designated late-night party hours. A substantial public relations exercise in local news media also ensured that parents of the thousands of outer-suburban revelers descending on the area each weekend felt assured of their safety and protection.10

The cover of The Weekend Australian Magazine in August 2008 captured Brisbane’s rapid makeover from “ugly duckling” of Australian cultural taste. Demographer Bernard Salt, a regular zeitgeist diagnostician for the paper, set the tone by observing: “Brisbane used to be almost a parody of suburban Australia … But now, creative people don’t feel they have to leave. It’s so exciting because it’s come from such a low, flat base.” The story was just one arm of the promotional material in the issue feting the third annual “Mercedes-Benz Fashion Festival” – another barometer of the city’s upward mobility. Salt hardly hesitated to malign Brisbane’s pre-boom image before celebrating the enlightened city emerging with an influx of residents from other states. “These days, it’s a bit like a fried egg,” Salt described the city. “It has this very dense, funky center stretching around Spring Hill, New Farm, the Gabba and West End, and all of that is cementing nicely.”

Such comments again bring to mind Ross’s (2008) argument that “creative” cities are successful to the extent that they garner erudite observations about bankable real estate hotspots for investors. The work experiences of actual residents employed in creative industries go missing in these accounts, as do the views of long-term locals loyal to Brisbane in spite of political conditions and speculator interest. In January of the same year, Salt had described Queensland as Australia’s “Peter Pan state” given its “ability to draw young, able-bodied workers in droves.” The lifestyle city imagined in these stories is a world where the aged, the unemployed, and the poor fail to register. Appearing in The Australian, one of few newspapers addressing a nationwide readership, Salt’s characterizations of Brisbane revealed a limited set of priorities on the part of non-Queensland readers. With some insight into the city’s history, however, his platitudes were further indication of why the creativity agenda needed to be strong. Years of ideological tyranny and entrenched civic corruption had severely damaged outsider assessments of the city’s economic potential.

On a local level, the gung-ho positivism of press coverage celebrating Brisbane’s transformed night life and boutique shopping districts catered for an expanding inner-city population. Many of these writers and readers had the luxury of choosing not to dwell on the state’s tainted past since they had not personally endured it. Brisbane’s younger residents, and the migrants that had arrived from further afield, had little need to modulate their views beyond the high-density and high-income lifestyles of the state’s south-east corner. The gulf that had always existed between Queensland’s north and the metropolitan south only grew in the boom, as commentators spoke of a “two-speed economy.” This diplomatic term avoided more antagonistic representations of a situation where city-based office workers could remain ignorant of the radically different conditions of the mining and resource hubs in the far-reaches of the state – and how these traditional industries contributed to their own good fortune in a “creative” economy.

Media sound bites certainly assist in appreciating the speed with which Brisbane moved from a city with little tolerance for diversity to one which promoted such tolerance as one of the hallmarks of a culturally sophisticated lifestyle. Whether “the lifestyle city” had adopted more encompassing attitudes was hardly the issue; ideological change was simply necessary at the level of business rhetoric if the city’s most ambitious and energetic workers were to be encouraged to stay. This is because in the space of a decade the lure of creative work had become pervasive in a range of other media formats pitching themselves to young, educated professionals. As the following section illustrates, technology advertising of the same period matched wider efforts to develop Brisbane’s profile as the destination of choice for urbane, creative workers.

The rise (and rise) of the frequent flyers

Mobile technology just gets more convenient for international travellers. Most good hotels have broadband and I find my BlackBerry now indispensable, though it’s a bit sad when you find yourself reading emails in the middle of the Forbidden City in Beijing!

Traveller Profile, The Australian Financial Review, 2007

The vital companion to the leisure affordances of newly minted creative cities is a flexible and fulfilling work culture. This hangover from the dot.com bubble has been the legacy of Baby Boomers coming of age in the US Cold War period who were influenced by West Coast anti-institutional thinking. The marriage of “counterculture” and “cyberculture” (Turner 2006) in figures like Stewart Brand proved a powerful influence on the way that technologies would enter the workplace already articulated to the widespread expectation that work could and should escape the nine-to-five office. By the 1990s, “the same machines that had served as the defining devices of cold war technocracy emerged as the symbols of its transfo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction: Work’s Intimacy

- Part I: The Connectivity Imperative: Business Responses to New Media

- Part II: Getting Intimate: Online Culture and the Rise of Social Networking

- Part III: Looking for Love in the Networked Household

- Conclusion: Labor Politics in an Online Workplace

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Work's Intimacy by Melissa Gregg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.