![]()

Part I

1

Health as Capability

The concepts of health and disease as well as related ideas such as illness, disability, impairment and so forth have profound importance in modern societies. A range of rights and obligations, often of great material significance and life-or-death consequence, flow from how these concepts are defined. Even at the international level, the concepts of health and disease are frequently used to evaluate societies or compel global action. The background or tacit understanding in the medical professions is that a person is healthy if she has no disease. And such a notion of disease is broad in that it includes infectious disease, chronic disease, injuries, poisonings, growth disorders, functional impairments and so on; all the conditions that are seen to be deviation from ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ functioning and the life course of a human being. And in public health or health policy-making, the aim is often to ‘contain and control’ diseases that lead to impairments and mortality. In doing this, such policies are seen to be improving or protecting health. The concept of disease, then, plays a crucial role in our conception of health.

The following discussion seeks to break the mutuality between disease and health, and also undermine some related views. Such views include seeing health ‘needs’ as largely requirements for healthcare goods and services or seeing the scope of health policy as being limited to healthcare policy, which, in the view of some, should be more accurately called ‘sickness care policy’. The following discussion on the scientific or medical understanding of health and disease is also aimed to express scepticism about measuring health as time lived without disease as many health economists do, and about conceptions of health in social justice literature as ‘normal range of species typical functioning’.

For anyone seeking to advance ethical or justice claims related to health or health-related goods, or even for arguments for how individuals should treat or relate to each other with respect to health, it is crucial to come to grips with the prevailing notion of health as well as to have a clear grasp of the health-related concepts that are being deployed in one’s own argument. Without a solid understanding of the dominant view of health, what is wrong with it, why it perseveres, and how the health concepts we are using stand in comparison, the claims we personally advocate could become vulnerable. Blindly relying on existing concepts of health and disease could wholly undermine our reasoning if the underlying concept is shown to be incoherent. Such vulnerability and incoherence is indeed evident in much of the health and human rights, health equity, or health and social justice literature.

There is also a growing body of sophisticated analysis concerning whether we should be worried about the causes, consequences or inequalities of health, or if we should be focused on inequalities of health across individuals or groups. But, it becomes clear quite quickly upon closer examination that even there the concept of health is used without much scrutiny. As Alan Cribb rightly describes it, health often seems to be ‘merely a useful compound label’ for a variety of things (Cribb, 2001, p. 22).

Though this chapter is not meant to be a historical project, the first section discusses some main points from the large body of literature that has developed critically evaluating the dominant view of health as the absence of disease. Such an overview is aimed to bring anyone interested in health justice up to speed in the philosophy of health and medicine debates. This is not the place for a comprehensive review as that would be a diversion from the primary goal of putting forward a concept of health as a capability. I aim broadly to lay out the theory underlying the prevailing view of health and its major criticisms, contribute some of my own criticisms, and lastly, present and extend an alternative theory of health.

The theory of health I am advancing rejects the plausibility and pursuit of a value-free and scientific notion of health, or one that is wholly centred on the concept of disease. Instead, I argue for a conception of health as a person’s ability to achieve or exercise a cluster of basic human activities. These activities are in turn specified through reasoning about what constitutes a minimal conception of a life with equal human dignity in the modern world. I arrive at this conception by modifying Lennart Nordenfelt’s theory of health, which defines health as the ability to achieve vital goals (Nordenfelt, 1987; Nordenfelt et al., 2001). I extend rather than wholly graft Nordenfelt’s argument into my project because it suffers from what I consider to be two significant drawbacks.

While Nordenfelt develops a plausible and coherent account of human health as the ability to achieve set of vital goals, he makes vital goals relative to each community and significantly dependent on individual preferences. By doing so, he comes up against problems with both socially relative concepts of health and subjectively defined well-being. Though there is important value in a community determining what constitutes vital goals for its members, Nordenfelt’s theory may under-recognize how social norms can actually impede the abilities of some individuals to achieve vital goals, or how certain valuable human functionings are not valued by the social norms of certain societies (e.g. female literacy, sexuality, or mobility). And, regarding preferences, even if a theory of informed preferences was deployed to counteract problems like expensive tastes or adaptive preferences, the central role given to preferences or subjective well-being in defining the health of a person is problematic. It is difficult if not impossible to compare the subjective experience of individuals. There needs to be an external viewpoint in addition to a person’s subjective viewpoint in determining whether a person is healthy or to what extent they are healthy.

Moreover, even when an individual’s preferences and the society’s social norms coincide, they both can evidence parochialism that undermines the achievement of vital human goals of outsiders and future generations. Where sparse material conditions of some communities lead to community norms endorsing fewer vital goals or lower thresholds of vital goals, Nordenfelt’s definition – as it stands now – would still consider that to be healthy. Overcoming both the drawbacks of subjective preferences and ‘bounded’ social norms and conditions in defining vital goals or health requires objective reasoning across human communities and individuals.

The theory of health proposed here replaces Nordenfelt’s empty set of preferences and society-relative vital goals with a human species-wide conception of basic vital goals, or ‘central human capabilities and functionings’. As a result, the health of an individual should be understood as the ability to achieve a basic cluster of beings and doings – having the capability to achieve a set of inter-related capabilities and functionings. Importantly, health is not defined by assessing the achievements of certain basic functionings or outcomes but by assessing the capability to achieve certain capabilities and functionings. But in some cases the only way to measure capabilities may be to measure actual achievements. Furthermore, by making health a ‘meta’ or overarching capability of exercising a cluster of capabilities, we are able to bridge the biomedical focus on the presence or absence of disease and its everyday social usage which usually describes an individual’s subjective well-being and abilities to function in the world. That is to say, one of the capabilities within a cluster of health capabilities is the capability of avoiding disease, and it is one among a range of other capabilities related to how the individual is feeling and doing things in the world.

The meta-capability concept also bridges philosophy of health and medicine debates with the debates on the capabilities approach and indeed, debates on social justice more generally. Theories of justice which seek to address health issues will now have a bridge to philosophy of health debates through the concept of health as a capability rather than simply deferring to prevailing notions or gliding superficially over the debates. Furthermore, I will argue that by integrating Nordenfelt’s theory with a theory of basic human capabilities such as that of Martha Nussbaum, some of the criticisms against Nordenfelt’s theory fall away. So to begin, first, I shall review the theory of health as the absence of disease, then Nordenfelt’s theory, and then, present my argument for conceiving health as the capability to achieve a basic set of capabilities and functionings.

Biostatistical theory of health (BST)

Starting in the early1960s contentious debates ensued in the United States and the United Kingdom over the scientific objectivity of the concept of disease and related concepts such as health, illness, malady and disability (Szasz, 1960; Marmor, 1972; Stoller et al., 1973; Blaxter, 2010). The debates centred on a position seen to be extreme and polemical – that ‘disease’ is simply a socially constructed category reflecting socially disvalued conditions or behaviours. These debates were initially within the field of psychiatry concerned with the definition of mental illness, but they quickly broadened out to all of medicine or healthcare. As a direct response to the debates Christopher Boorse published a series of four articles in the late 1970s with the aim of establishing a scientific and value-free definition of health and illness (Boorse, 1975, 1976a, 1976b, 1977).

Boorse’s ambitious aim was to create a theory of health as well as a theory of medicine, since the aim of medical practice is generally understood to be to address the health needs of human beings. He assumed, like so many others still do, that clinical medicine/healthcare and human health are mutually encompassing ideas. If the concept of health is defined, then the scope and purpose of medicine becomes defined; if the scope of medicine is defined, then health becomes defined, a supposedly perfect mutuality.

While the notion of health as the absence of disease preceded Boorse, during the three decades following its initial presentation, Boorse’s theory has indeed become standard in medical teaching and practice. At the same time, it has provoked tremendous criticism and often serves as the referent background theory to much of the philosophy of health and medicine literature. Boorse’s argument for ‘theoretical health’ presented in its amended 1997 form contains the following four components:

The reference class is a natural class of organisms of uniform functional design; specifically, an age group of a sex of a species.

A normal function of a part or process within members of the reference class is a statistically typical contribution by it to their individual survival and reproduction.

A disease is a type of internal state which is either an impairment of normal functional ability, i.e. a reduction of one or more functional abilities below typical efficiency, or a limitation on the functional ability caused by environmental agents. [emphasis mine]

Health is the absence of disease. (Boorse, 1997, pp. 7–8)

It may be helpful to recapitulate and interpret the four points in reverse, starting from the conclusion. A living thing is healthy if it is not diseased. To be diseased means that somewhere in the inter-related and organized physiological structure, a biological part or process is ‘functionally reduced’ to a level ‘below’ the normal distribution of such values (typical efficiency) in similar individuals or limited by environmental agents. Normal functioning refers only to the statistically typical contributions parts and processes make to the individual’s survival and reproduction. And, an individual’s functioning is compared to those of a reference class made up of other individuals of the same sex and age of the same species. The three premises and conclusion of the theory have often been summarized as health being the absence of disease or health as species typical functioning.

The basic underlying idea that Boorse is advancing is that human biological and mental functioning is geared towards or ‘designed for’ individual survival and reproduction. And the biological functionings of parts or processes that are not causally related to survival and reproduction are excluded from the domain of health. As a result, a physical deformity, even though it may be atypical, if it does not directly affect survival or reproduction is not categorized as disease. And if it is not a disease it does not relate to health. Moreover, instead of using the standard of ideal values or even population average values, the statistically normal distribution model makes use of a range of values that occur most frequently across a reference class or population of human beings.

The link between statistically normal and what occurs most frequently is important to recognize because not only does it acknowledge variation in functioning among the human species, it is also unable to say if someone is less or more healthy within the range of normal or typical functioning. For example, the most frequently occurring values of a functioning may not be the most efficient contribution to survival. Think of the most frequently occurring resting heart rate for a group of thirty-year-old men versus that of a sub-group of thirty-year-old male athletes. Even though the heart and other body parts of these athletes may be making a more efficient contribution to survival, the idea of frequency is only about how often something occurs. To be healthy means that the measurement values of functionings of parts and processes are not rare or atypical, and fall somewhere within the most often occurring values in an age–sex reference class.

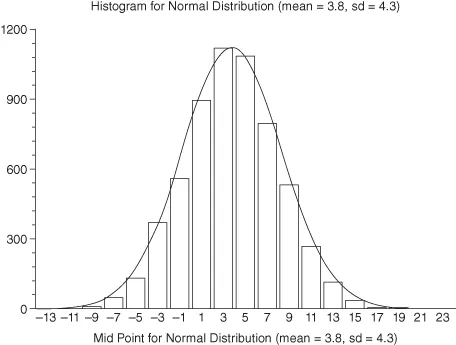

For those unfamiliar with statistics, the graph on the next page may be helpful to understand the concept of statistical normal distribution that Boorse is using. Imagine that the graph represents the measurements of a biological part’s functioning in a reference class of individuals. The different bars in the histogram represent the frequency of different values occurring in the reference class. The average value or mean is 3.8, and one standard deviation is 4.3. This means that 68.2 per cent of the values fall somewhere between 3.8 ± 4.3, and 95.4 per cent of values fall between 3.8 ± 8.6. Individuals whose ‘test results’ show a measurement value below -4.8 or above 12.4 would be abnormal. Boorse never actually identifies a threshold for disease.

However, if we are to follow through on the use of the statistical normal distribution cure, health would be the most frequent 95.4 per cent or ‘normal range’ of values, and the remaining values in the tails would be disease. But Boorse thinks that people in the ‘below’ tail would have disease or show pathology while those on the ‘above’ tail may have ‘positive health’. But he seems to be conflating two distinct exercises here. One is assessing simply if and at what level the organ is functioning, and the other, how well it is functioning. If it is only the first, we should classify both tails as disease, not just the ‘below’ tail. A heart beating too slowly and one that is beating too fast are both likely to interfere with survival and reproduction. But if we are taking measurements of functional efficiency, then the distribution is of how well the part or process is working, making the more efficient tail more acceptable as ‘positive health’. But without a specific efficiency test, we are only able to plot the values of measurements and identify both tails.

In any case, Boorse also put forward a theory of illness in order to capture the social values aspects of disease and health. Recognizing the discontinuities between his objective definition and the social usage of the terms, he proposed a secondary theory of illness. He suggested the use of the term ‘illness’ in medical practice to identify the sub-class of diseases to which a society attaches normative judgements.

One of the more provocative aspects of Boorse’s theory is that he claims that mental disease can also be defined similarly through the tabulation of the normal distribution of mental functionings across human beings. What is most common or frequent in mental functioning across a reference class of human beings becomes the standard for what is healthy. Indeed, Boorse developed his theory initially in order to clarify psychiatric issues, but it is controversial because, unlike biological functioning, it appears easier to question the assertion that what occurs most frequently in mental functioning among a group of human beings should be viewed as what is healthy. It is perhaps in relation to mental functioning that the tension becomes clear between objectively describing health as the most frequently occurring functioning versus the idea of health as describing an ideal or excellence in human functioning.

Boorse’s theory of disease, health and illness has profoundly shaped the parameters of the debates in the philosophy of health and medicine since the 1970s. The idea of health as being a range of species typical functioning and a threshold (i.e. the lower tail) has also been used in political philosophy (Daniels, 1985; Rawls, 1993, pp. 182–185). Despite the number and range of criticisms accumulating for many years, Boorse attempted a rebuttal only in 1997 (Boorse, 1997). Since then, he has also presented commentaries on the some of the leading alternative theories (Boorse, 2002, 2004). In the 1997 rebuttal Boorse bundles all the numerous critiques into three general categories including technical objections, objections from biology and objections from medicine. I focus here on three criticisms related to the baseline of functionings and role of the environment, the notion of pathology, and biological purpose as they highlight the weaknesses that I find particularly troublesome.

The baseline and the environment

To start with the first criticism, referring back to his four-point formulation as stated in 1997, Boorse argues that a disease is either a reduction below typical efficiency or a limitation of functioning caused by environmental factors. The first type of reduction entails a comparison of functioning between individuals and their reference class. The second type of limitation refers to the decrease in functionings of an entire population. He added the second clause in 1997 in order to accommodate for environmental catastrophes where the entire population is affected; where the entire population distribution curve shifts. What Boorse initially thought of as a fixed baseline of species-typical functioning he now recognizes can move, such as when the entire population is affected by a common factor. Without adding such a clause, reduced health functionings in an individual would be classified as healthy because the rest of the population would also have reduced functionings. This problem arises as a direct consequence of health being defined as the most frequent or common occurrence, rather than reflecting another principle such as the best, ideal or excellence of functioning of a human being.

This amendment, however, does not solve Boorse’s problem regarding the influence of the environment on the entire reference class or entire population. Industrial accidents like Chernobyl or Union Carbide can indeed affect so many people that one would need a way to escape defining health wholly as the most frequently occurring values in a population. However, this amendment is only useful if one thinks that the baseline before the environmental event was somehow objective or natural. And the clause depends on recognizing changes in the distribution of values before and after a visible or sudden environmental event with exposure to material ‘agents’. Let me address the latter point first. Where no such discrete event occurs, or something like blanket air pollution is not visible, the majority of the population may still be exhibiting reduced functionings due to less patently obvious factors or agents.

For example, let us assume that we did not know that smoking causes lung cancer and other impairments. If every member of a population smokes, and it has always been so, we would not be able to tell that the people were experiencing reduced lung functioning. And, if we suspected that the lung functioning was reduced, we would not be able to recognize why because there would not be a comparison group which does not smoke. So, if we go by frequency, reduced lung functioning looks like the natural human condition and, if we did think that lung functioning could be better, we would probably end up looking for genetic differences between individuals as the cause.

Now consider the former point about the baseline. When we do find that smoking causes reduced lung functioning, under Boorse’s theory, the level of smoking in the population will determine what we consider to be normal lung functioning. There is no environmental limitation, as Boorse imagines, related to smoking, so what is most frequent functioning would still continue to be what is healthy. If we use another cause of disease, such as consumption of alcohol, salt or fat, we still have the same problem.

The research from social epidemiology shows that distribution of life expectancy and health functionings across the entire population are determined by social processes and institutions (Marmot and Wilkinson, 1999; Berkman and Kawachi, 2000). How people relate to each other, entrenched social norms, or average social practices may be holding back the entire distribution curve from where it could otherwise be. What is considered to be a healthy value now because it is within the most frequently occurring range could move to the disease part of the distribution if the social arrangements were different. The consequence of this is that the baseline of typical functioning of a population is socially determined; it is not a natural baseline. The measurements can be natural facts, but the causes of the natural facts do not originate in nature. Broad social determinants influence the baseline of health functionings, and this is a large part of what makes up the differences in health achievements across national populations.

This...