![]()

1

Facts, figures and myths

A decade ago virtually no one except geologists had heard of tantalite, or ‘coltan’ as it is known in the Congo. Today, it is discussed at the United Nations, in the media, at student teach-ins and on activist websites, and is linked to some of the worst atrocities to blight the planet – mass rape, slave labour, extrajudicial killings and the illegal arms trade. There is even Coltan the novel, and ‘Coltan Rush’, a ‘groove against war’ by the Afro-jazz band, Bantunani. Whereas coltan was once an obscure mineral, there is now contestation over how it is produced, traded and sold. A politics of coltan has been brought into existence, one that encompasses warlords, transnational corporations, determined activists, Hollywood film stars, the rise of China, and the latest iGadget from Apple Inc. How did this happen? Why did an obscure mineral achieve such infamy? This volume analyses the two issues that have come to define coltan politics: the relationship between coltan and ongoing violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (hereafter DRC or ‘Congo’), and contestation to reshape the global coltan supply chain.

Coltan gained widespread attention from journalists, activists and social scientists in 2001, when reports by the United Nations linked it, and other minerals, to ongoing violence in the DRC. Armed groups waging war were reportedly seizing control of coltan mines to take advantage of the record high prices which the mineral was fetching on the international market. Militia leaders boasted to journalists about the millions of dollars they were making in profits. In a complicated and seemingly unending conflict in which causes and motivations seemed to change from year to year, this provided a moment of clarity: armed groups were fighting to control coltan deposits and using violence against civilians who got in the way, and coltan was being bought by multinational corporations and used to make electronic gadgets, such as mobile phones, laptops, iPods and personal digital assistants, for Western consumers . . . or so the story went.

Over the 2000s the coltan industry became a ‘lightning rod’ for those concerned about conflict in the Congo. Activists, frustrated by a general lack of interest, suddenly had a symbol they could use to link the public to violence in far-off Congo: the mobile phone or ‘cell’ phone. Ordinary citizens became implicated. A US Senator claimed ‘without knowing it, tens of millions of people in the United States may be putting money in the pockets of some of the worst human rights violators in the world simply by using a cell phone or laptop computer.’1 Governments held inquiries into allegations that corporations from their countries bought coltan that had passed through the hands of armed groups; the United Nations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) kept publishing reports implicating more and more companies in the illegal trade of natural resources from the DRC; and activists urged consumers to boycott products made from ‘conflict minerals’. There are some inaccuracies and exaggerations in NGOs’ and activists’ accounts of cause and effect about coltan and conflict, but there is a determination to politicize the exploitation of natural resources such as coltan because of its perceived relationship with inequity and violence.

Coltan or tantalum?

Coltan is an abbreviation of columbite-tantalite, a mixture of two mineral ores, and is the common name for these ores in eastern Congo. Tantalum is the name of the metal extracted from tantalite-bearing ores, including coltan, after processing. Scholars, journalists and activists who have sought to understand and publicize the relationship between the tantalum supply chain and violence in the Congo, popularized the term coltan because this is the name used in the DRC. ‘Coltan’ has subsequently become widely used outside industry and scientific circles. Where the term ‘coltan’ is used in this volume, it refers only to unprocessed tantalite-bearing ores from the DRC.2 ‘Tantalite’ is used when referring to tantalum-bearing ores in general or from countries other than the Congo. ‘Tantalum’ is used when referring to the processed metal. This volume analyses the global tantalum industry to provide some context to the economic forces and international actors that shape demand for coltan, but the volume is primarily concerned with coltan from the Congo, not tantalite or tantalum more generally. The title of this volume reflects broad recognition of the term ‘coltan’ and the fact that the political story worth telling is about coltan.

Volume structure and arguments

The present chapter describes where tantalum is found and produced and what it is used for, and analyses why its price has fluctuated, looking particularly at the causes of the price spike in 2000. The chapter puts to rest some popular myths about coltan and tantalum. For example, the Congo is not the repository for 80 per cent of the world’s tantalite reserves nor does it produce 80 per cent of the world’s tantalite, as is often claimed. Tantalite is also not a special mineral subject to ever-increasing demand. It has economic characteristics similar to other commodities: price changes are cyclical, and supply and demand ebb and flow.

Chapter 2 analyses the organization of production, trade and markets. Most tantalite is extracted in modern industrial mines in politically stable conditions where property rights are secure, and is sold under long-term contracts to processors. By contrast, coltan is produced using artisanal (pick and shovel) and small-scale mining methods. These methods are used because of a combination of factors unique to the DRC: the timing of the price spike in 2000, the geological characteristics of coltan, cheap labour and, most importantly, the weakness of state institutions. The latter has resulted in unclear and insecure property rights, impunity for breaking contracts, and poor infrastructure. Whereas in other countries customary institutions such as chiefs enforce contracts and protect property in the absence of a strong state, in the DRC these institutions have been weakened by war. The ways in which production and trade of coltan are organized in the DRC has created specific opportunities for profit-making by armed groups, which have been attracted to coltan for this reason. Economic networks centred on Rwanda have been pivotal to both the legal and illegal trade in coltan out of the DRC to the international market.

Chapter 3 analyses the relationship between coltan and conflict in the DRC. It commences by arguing that, while natural resources have played a role in conflict, this is typical of other conflicts as well and does not make violence in the Congo distinctive. The chapter summarizes the five waves of violence that have afflicted eastern DRC since the early 1990s, and analyses the degree to which coltan and other minerals have been factors in belligerents’ strategies and motivations. The DRC conflict is not a single-issue conflict, it is not primarily over natural resources, and the motivations of warring parties have evolved over time. While control of the minerals sector including coltan has been contested by armed groups, they have also fought over agricultural land, opportunities to tax trade more generally, political dominance, national security, ethnic grievances, and to settle scores. Relative to other minerals and other motivations, coltan is not that important as a factor causing violence, although in 2000 and 2001 it was more significant, due to high prices, than in subsequent years. There is also no direct causal link between coltan and violence against civilians, including the mass sexual violence that characterizes conflict in the DRC. The fact that armed groups that control coltan mines and tax the coltan trade also commit rape and murder is incontrovertible. However, there is no evidence that this violence would stop if coltan disappeared from the equation.

Chapter 4 traces the evolution of advocacy, campaigns and initiatives focused on reshaping the coltan and tantalum supply chains in order to end war in the Congo. It analyses the objectives of ten initiatives and the tactics they employ, which range from celebrity testimonies on YouTube, to boycotts by college students of mobile phones containing ‘conflict minerals’, to ‘freeze actions’ on city streets in the Netherlands, to pictures of gorillas on phone recycling campaign posters in Australia, to training in ‘ethical mining’ for Congolese miners. Seven global initiatives that focus on improving governance in extractive industries more generally, and therefore have some potential to reshape the coltan industry, are also discussed. The tactics adopted in coltan campaigns expose underlying differences of opinion about the most effective solutions to the conflict. The key difference is whether the priority should be cutting off coltan profits to armed groups, or building the capacity of the DRC state to better manage development of natural resources. The chapter analyses the challenges these campaigns face in a global activist ‘marketplace’ crowded with competing global justice issues. The chapter argues that the political significance of coltan lies not in its actual causal link to violence, but in activists’ effective manipulation of mobile phones (which contain tiny quantities of tantalum) as a symbol of how ordinary people and multinational corporations far from Africa are implicated in the Congo’s coltan industry and therefore its conflict.

Chapter 5 analyses the future of coltan politics. It argues that activist campaigns have led to changes in the tantalum supply chain, in that Western corporations are pulling out of the market for coltan, causing a reconfiguration of the industry. However, this has stopped neither the trade in coltan nor profits filtering back to armed groups. China has become the chief destination for coltan as Chinese firms carve out a role in the global minerals, metals and manufacturing industries. The future outlook for tantalum is positive, but demand for the end products containing it will increasingly come from markets in developing countries. There are three key lessons from the politics of coltan for the politics of natural resources more generally. First, companies should be aware that, no matter how innocuous they think their business is, with time and money activists can create and propagate a compelling narrative of injustice that implicates their firm. Second, while non-state actors such as NGOs and multilateral organizations have successfully carved out a role in natural resource politics, this role can never be assured, given the rise of new corporations and countries, especially China, in the global minerals and metals markets. Third, if Western activists want to maintain the influence they have fought so long and hard to achieve, they need to devise messages that resonate with consumers in developing countries, seek ways to pressure corporations whose domestic reputation is little affected by their actions overseas, and find methods of ensuring that governments, with a tradition of not engaging with domestic political issues in other countries, will care about what their corporate citizens are doing.

There are two issues that the volume does not explore. First, it does not discuss how revenue from coltan should be invested and distributed. Certainly resource revenues are of critical importance to economic growth and the alleviation of poverty in the Congo. However, a discussion of the appropriate management and use of coltan revenues requires a wider survey of the many natural resources found in the Congo (including cobalt, copper, diamonds, gold, manganese, oil, timber, tin, tungsten, uranium and water), not just coltan, and is therefore beyond the scope of this volume. Second, while the volume analyses coltan initiatives and in the conclusion weighs up whether a concerned citizen should engage in these, it is not a ‘how to’ manual for activists or governments seeking to restructure the coltan supply chain.

Due to its broad political scope, this project was informed by many different fields of scholarship. However, in an effort to keep the volume readable, many facts and scholarly arguments are not directly referenced in the text. Instead, readers wishing to explore in more depth the various discussions and arguments to which this volume refers should consult the Selected readings section.

All monetary amounts are in United States dollars. All measurements are in metric (kilograms and metric tonnes), except tantalum prices which are in dollars per pound (the market convention).

When the volume uses the term ‘armed group’, this includes the DRC army.

Properties and characteristics of tantalum

Tantalum is classified as a ‘minor metal’. It is grey-blue through black in colour, has the symbol Ta in the periodic table of the elements and its atomic number is 73. Tantalum’s metallurgical properties make it indispensable to hi-tech industries. It is an excellent conductor of electricity; it has a very high melting point of 3,017°C (5,463°F), even when conducting electricity; it is very strong; it can be easily shaped and formed into different products; and it is highly resistant to corrosion.

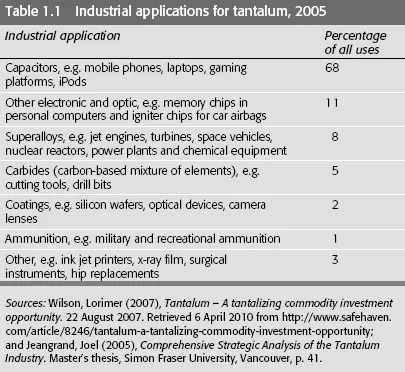

These characteristics make tantalum ideal for a range of metal products. Its ability to conduct electricity is useful for mobile communications devices; its high melting temperature enables alloys (mixtures of metals) containing tantalum to remain in a solid state in extremely high temperatures, rather than melt; and its anti-corrosive characteristics mean that it will not rust or be affected by acidic environments. Table 1.1 shows the proportion of global tantalum production used for various industrial applications.

About two-thirds of tantalum production is used in the electronic capacitor industry to make tantalum capacitors. In the same way that a dam stores water from a river and regulates its flow to crops for agriculture, capacitors store and regulate the flow of electricity from batteries, or other power source, to the parts of an electronic device that perform functions, such as the display windows of mobile phones or storage areas for digital information. Capacitors are widely used in digital electronic devices such as personal digital assistants, iPods, digital cameras, liquid crystal display screens, DVD players, gaming platforms such as Nintendo, Xbox and PlayStation2, laptops and mobile phones. Tantalum capacitors are ideal for these products because, even in the crammed space inside a mobile phone, for example, they will not cause surrounding metals and plastics to heat up and melt because of their good heat conduction properties. Furthermore, only tiny quantities of tantalum are required – the average mobile phone contains less than 20 milligrams of tantalum. Tantalum is partly responsible for the miniaturization of electronic devices and for the growth of markets for these products.

There are capacitors made of other materials, including ceramics and aluminium. These types of capacitors are less expensive than tantalum capacitors. However, they can store less electricity per unit volume than tantalum. For example, to get equal performance from a telephone containing a tantalum capacitor on the one hand, and a telephone containing a ceramic capacitor on the other, the latter would have to be considerably larger – ma...