![]()

Part I

Setting the Scene

Part I sets the scene. It dismisses the simplistic view that participating in the global economy automatically solves problems of poverty and inequality. Part II sketches a positive scenario in which globalization provides the opportunity for reducing poverty and income inequality, but argues that grasping this opportunity requires a clear strategic focus and the effective management of innovation. Part III, by contrast, is more pessimistic. It suggests that, while some may gain from globalization, the very nature of global production and trading systems may act to enhance poverty and make income distribution more unequal for others. The final chapter considers the implications of the more pessimistic outcome outlined in Part III both for poverty-focused policies and for the sustainability of globalization itself.

The opening chapter focuses on the dynamics of globalization. It describes the primary character of the contemporary phase of globalization, and contrasts this with the pattern of globalization during the nineteenth century. Chapter 2 summarizes the literature on global poverty and contrasts two perspectives on globalization, poverty and inequality. The first is a residual explanation, favoured by the World Bank and other proponents of globalization. It argues that the bulk of global poverty is a result of the failure of producers to engage with globalization. If they participate in the global economy, it is believed, poverty levels will be reduced. The second perspective argues that poverty and inequality are relational to globalization. Instead of resolving global poverty, the workings of the global economy deepen the problem for many producers who are unable to compete effectively in a world of growing surplus production capacity.

![]()

1

Global Dynamics

1.1 What’s the problem?

In July 1969, I left South Africa as a political refugee. It was a blustery winter day and, as the boat sailed out of Cape Town harbour into the ‘Cape of Storms’, I looked up at Table Mountain. It had risen to the occasion to mark my departure with a fabled table-cloth covering. And I remember thinking: ‘I will never return to my homeland. The forces of racial and class domination which have subjected the majority of the population to poverty and political repression (and forced me into exile) are too well entrenched. It will change, but not in my lifetime.’ I shed copious tears as these thoughts swirled around my head.

For the next fifteen years I revelled in my identity as an ‘oppositionist’. I had participated in the struggle against apartheid, and had steeped myself in the Marxian culture of the times. I easily transferred this world-view and identity to broader pastures and, with many others at that time, engaged in debates and researched the ‘flaws in the system’. Poverty and repression were endemic; low-income countries were caught in a trap of dependency, and would not progress without fundamental structural change.

But things changed. I got tired of working against, rather than for, and wanted to feel that I was constructing rather than destroying. Moreover, not only were the socialist economies of Eastern Europe floundering, but my eyes were opened to historical reality by a paper comparing labour conditions in South Africa’s mines with those in Stalinist Russia; by comparison, South Africa seemed like a holiday camp. And then a series of professional opportunities opened up to combine my academic life with policy advice. Over a seven-year period (why do phases always last seven years?), together with colleagues, I provided policy support to a range of countries, including Cyprus, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Kenya and, in later years, Armenia, Kazakhstan and Russia. Yes, the world was filled with positive and negative energy, and it was uncertain. But the glass was half full – on balance there were enough positives in the system to make progress possible.

Then, in the late 1980s, the impossible seemed to happen. South African politics became unstuck. Suddenly, new students arrived on the scene, not just having experienced the all-too-familiar torture and solitary confinement, but expectant of returning home, and into government, after their studies. And then my political exile was lifted and I, too, was allowed back. Old contacts were renewed, and, in combination with comrades in the African National Congress and the Confederation of South African Trade Unions, I embarked on a thirty-month multi-sector investigation of the determinants of competitiveness with a view to constructing an industrial policy for the new South Africa.1 It was a world of new opportunities, growth and optimism about what could be achieved in a new democratic political dispensation.

At about the same time, I and my colleagues at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex were developing a programme which reinforced this optimism. Our view was that it was not a matter of whether to participate actively in the global economy. That was a given, both because of the opportunities it offered, and because international political pressures made it difficult for low-income economies to withdraw from the global economy. Rather, the challenge was how to join in the global economy in a manner which provided for sustainable income growth. Similarly, with my colleagues at the Centre for Research in Innovation Management at the University of Brighton, I came to be concerned less with policy design than with policy implementation (the hard part of the story). This led to an extended collaboration with friends and colleagues at the University of Natal in South Africa. We focused on researching the determinants of successful innovation management, and on actively assisting groups of firms in the auto, clothing and furniture industries to become globally competitive. We also worked closely with the sectoral groups of the Department for Trade and Industry, which was responsible for industrial policy. The glass was still half full, the possibilities were numerous.

But there was a nagging worry. I thought back to the firms I had worked with in so many low-income economies over the previous decade, and how much less dynamic they were than their South African counterparts. How were they managing to cope with the pressures of globalization? And then one day, when I was working in a furniture factory in Port Shepstone in South Africa, the penny dropped. The firm reported that it had gained little from currency devaluation – the gains had all been appropriated by buyers. For example, the price it received for bunk beds fell from £74 in 1996 to £48 in 2000. Thinking that this might have been an aberration, I interviewed a second firm; its records were less up to date, but it reported that the sterling price it received for bunk beds also fell, from £69 in 1996 to £52 in 1999. So, what about other products? At that time, we were working with a group of three wooden-door exporters, and their story was similar. The largest exporter had seen the sterling price of its major export item (accounting for 40 per cent of sales) fall by 22 per cent between 1996 and 2000. Like the other furniture firms, it managed to stay in business only because of devaluation. In none of these cases was productivity change anything like this rate of price decline.

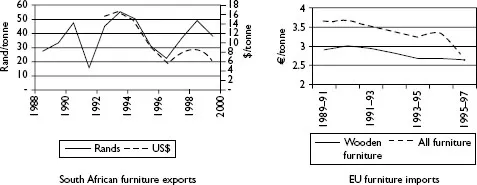

Well, perhaps this was a phenomenon unique to Natal-based manufacturers, or to the exporters of bunk beds and doors? What story did the aggregate data tell for other South African furniture exporters? Figure 1.1 recounts their experience. Between 1988 and 2000, South African furniture exports had grown tenfold in local prices, reaching $82 million in 2000. But they had done so on the back of falling unit export prices, made possible by currency devaluation. Perhaps this was a story unique to South Africa? What had happened to the price of global furniture exports? Figure 1.1 reports the evidence, using EU imports as a surrogate for world prices, and evening out year-to-year fluctuations by using three-year moving average prices. It tells a similar story – sustained falling unit prices.

Figure 1.1 Unit price performance of South African furniture exports and EU furniture imports, 1988–2000

Source: South African data was drawn from Industrial Development Corporation database; EU data from the European Commission’s Eurostat Statistical Office’s database on external trade

My perspective had shifted. The glass was no longer half full, it was half empty. If South African firms found it difficult to manage the pressure of global competition, how much more difficult would it be for firms in other low-income countries in which I had worked, all of whom had much less sophisticated manufacturing capabilities than did their South African counterparts. Did it still make sense to believe that all could gain from globalization, if only they followed our prescriptions for upgrading their capabilities? Perhaps, instead of placing their faith in books on innovation management, firms and governments would profit from work of an earlier commentator (box 1.1),

Box 1.1 What did Lewis Carroll have to say about globalization?

‘Nearly there!’ the Queen repeated. ‘Why, we passed it ten minutes ago! Faster!’ And they ran on for a time in silence, with the wind whistling in Alice’s ears, and almost blowing her hair off, she fancied. [For this, read a country opening up to global competition.]

‘Now! Now!’ cried the Queen. ‘Faster! Faster!’ And they went so fast that at last they seemed to skim through the air, hardly touching the ground with their feet, till suddenly, just as Alice was getting quite exhausted, they stopped, and she found herself sitting on the ground, breathless and giddy. The Queen propped her up against a tree, and said kindly, ‘You may rest a little now.’ [Unused to competition, firms begin to innovate – a new process, it’s tiring.]

Alice looked around her in great surprise. ‘Why, I do believe we have been under this tree the whole time! Everything’s just as it was!’ [Despite this innovation, the firm is making little competitive progress – it wants to know why.]

‘Of course it is’, said the Queen. ‘What would you have it?’

‘Well, in our country’ [the days of import substitution, before opening out to imports], said Alice, still panting a little, ‘you’d generally get to somewhere else – if you ran very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing’ [that is, learning how to innovate after years of relative stagnation].

‘A slow sort of country!’ said the Queen. ‘Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!’ [The pressures of global competition are insuperable for some.]

Source: Through the Looking Glass (Carroll 1916)

who had inadvertently provided a window into the challenges of globalization in the late twentieth century? In the case of Alice, it didn’t matter how fast she ran, the frontier still seemed an insuperable distance away.

This book looks at the impact of globalizing production and trade systems on poor countries and poor people. After the pervasiveness of global poverty and inequality is documented in chapter 2, part II examines the case for a win–win outcome to globalization – a half-full glass in a world of uncertainty. Chapter 3 provides a theoretical perspective for generating sustainable incomes, and chapter 4 summarizes the practical steps of innovation management that are required to translate this theoretical agenda into practice and examines the role played by global buyers in connecting producers to customers. In chapter 5 we see evidence of the successful global spread of production capabilities in three key sectors – textiles and clothing, furniture, and autos and components.

By contrast, part III looks at a win–lose outcome to globalization – the glass as half empty; the very success of some in the global economy is a cause of the poverty of others. In chapter 6 this is evidenced by an examination of the performance of the global price trends of approximately 4,000 products over the period 1988–2002, and the different price behaviour of low-income economy exports and imports over a similar period. In chapter 7 we explore ways in which this price outcome to globalization may lead to either a win–win or a win–lose outcome, and conclude that, for many, the latter is more probable. Much of the discussion in these two chapters focuses around the nature of the global labour market and the existence of a reserve army of increasingly educated labour. The recent experience of China and its impact on the global economy is a central part of this story. Given this outcome, the final chapter examines the implications this holds for policy, particularly in those countries in Africa and Latin America which have failed to gain substantively from the global integration of production and trade. It also explores the sustainability of globalization in the context of the growing inequality arising from its extension.

Of course this is not the fi...