eBook - ePub

Water

About this book

Water is our planet's most precious resource. It is required by every living thing, yet a huge proportion of the world's population struggles to access clean water daily. Agriculture, aquaculture, industry, and energy all depend on it - yet its provision and safety engender widespread conflict; battles likely to intensify as threats to freshwater abundance and quality, such as climate change, urbanization, new forms of pollution, and the privatization of control, continue to grow.

But must the cost of potable water become prohibitively expensive for the poor - especially when supplies are privatized? Do technological advances only expand supply or can they carry hidden risks for minority groups? And who bears responsibility for managing the adverse impacts of dams funded by global aid organizations when their burdens fall on some, while their benefits accrue to others? In answering these and other pressing questions, the book shows how control of freshwater operates at different levels, from individual watersheds near cities to large river basins whose water - when diverted - is contested by entire countries. Drawing on a rich range of examples from across the world, it explores the complexity of future challenges, concluding that nations must work together to embrace everyone's water needs while also establishing fair, consistent criteria to promote available supply with less pollution.

But must the cost of potable water become prohibitively expensive for the poor - especially when supplies are privatized? Do technological advances only expand supply or can they carry hidden risks for minority groups? And who bears responsibility for managing the adverse impacts of dams funded by global aid organizations when their burdens fall on some, while their benefits accrue to others? In answering these and other pressing questions, the book shows how control of freshwater operates at different levels, from individual watersheds near cities to large river basins whose water - when diverted - is contested by entire countries. Drawing on a rich range of examples from across the world, it explores the complexity of future challenges, concluding that nations must work together to embrace everyone's water needs while also establishing fair, consistent criteria to promote available supply with less pollution.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Freshwater: Facts, Figures, Conditions

Freshwater is our planet’s most precious resource. Every living thing needs it to survive, but in many places people increasingly face difficulty finding it. In Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, some two-thirds of the city’s two million residents rely on private water deliveries by teamsters because the region is running out of groundwater. Those who cannot afford to pay queue up at spigots located outside mosques to gather free water when it is available. It is not unusual to see women collecting families’ shower water to re-use for laundry.

While international aid agencies have proposed reducing rural groundwater mining, building additional wells, and restricting agricultural irrigation, no one seems to think these remedies will be enough to help Sana’a. Some believe the underlying problem is a lack of rain made worse by climate change. Others point to continued in-migration from the country’s poor, drought-stricken rural areas – to the tune of 150,000 people a year. Some things are certain: the city cannot afford additional water mains; most of Yemen’s aquifers are drying up; and the government has been battling Shiite Muslim rebels in the north, a separatist movement in the south, a resurgent Al Qaeda movement, and piracy in the Gulf of Aden. In short, any remedies to its water shortage must reckon with Yemen’s violence, instability, and poverty.1

If too little freshwater is Yemen’s problem, how to pay for it is never far from the minds of most Bolivians. In 1997, in order to receive a World Bank loan, the country’s congress voted to turn over control of its water utilities to two corporations – one, French and the other, American. Both imposed strict rules on urban residents’ ability to collect rainwater from their roofs, imposed charges for drawing water from private wells, and increased service rates by nearly 200 percent.

Responses to these actions were swift. Uprisings occurred in Cochabamba and La Paz as poor, angry residents protested these actions, and martial law was imposed in an effort to restore order. Bechtel and Aguas de Illimani SA (a subsidiary of France’s Suez), the companies granted licenses to operate Bolivia’s utilities, countered that higher rates were necessary to expand service and compensate for previous government corruption that had squandered resources which could have been used to improve water delivery and treatment infrastructure. Their defense was to no avail. Both companies abandoned their operations and, in 2005, President Evo Morales established a Ministry of Water and charged it with overseeing public supply and providing universal access. The country’s constitution now guarantees a right to water and bans privatization. Despite reform, provision remains woefully inadequate because the country is too poor to invest in reliable freshwater supplies or better treatment. In 2008, the government appropriated a mere $800,000 for nationwide improvements.2

While talk in many parts of the world focuses on the possibility of “water wars” prompted by shortages and exorbitant cost, in other places too much water is the problem. In the past decade, South Asia, China, and the American Middle West and South have endured severe floods that have destroyed homes and farms and forced people to flee from rising waters. We know floods occur naturally, and that human folly sometimes worsens its effects (as, for example, when people choose to live in floodplains or low-lying coastal zones prone to storm surges). However, politics sometimes intrudes to worsen its impact in other ways. For instance, at the height of the catastrophic Indus River basin floods in Pakistan in 2010, wealthy landowners in southern Sindh province dynamited dikes to protect their flood-threatened properties. Levee systems were breached at junctures where wheat, rice, and cotton were cultivated by poorer villagers, powerless to oppose their wealthy neighbors’ heavily armed militias. Breeching the levees not only worsened a natural disaster, but ensured that its impacts fell most heavily on those least able to recover.3

Other freshwater problems are chronicled daily. In Hungary in 2010, a ruptured tailings dam from a poorly managed chemical plant unleashed millions of gallons of heavy metals and other contaminants into local rivers – threatening drinking water and contaminating farms. In Ethiopia, meanwhile, thousands of villagers eagerly await completion of a massive dam, Gilgel Gibe III, that promises cheap electricity and water for irrigating staple crops. Downstream, however, some Kenyans fear the project may impede river flows that support their fisheries and farms.4

Are these problems isolated incidents, or do they point to a global crisis? This book contends that they are inter-connected threats to our livelihoods and welfare. What links them is the concept of sustainability: ensuring that the various ways we manage freshwater for growing food and fiber, producing energy, making and transporting goods, and meeting household needs do not impair the welfare of other living things, or of future generations. Sustainability also means promoting development, protecting the environment, and advancing justice. Yet the way freshwater is managed often does just the opposite. Moreover, when we abuse other resources that interact with water we create unsustainable conditions for freshwater management in two ways.

First, any actions that exhaust, deplete, degrade, or pollute water adversely affect both nature and people. Once a dam is built, it alters a stream’s flow and its surrounding physical and social environment. Similarly, when a river is diverted from its course to slake a city’s thirst, the region in which the river’s course was changed may find its economy and politics forever changed. Second, many actions designed to avert floods or drought, protect or restore water quality, or provide additional freshwater often fail to account for a society’s ability to achieve these objectives fairly, and without unjustly burdening certain groups.

The aim of this book is two-fold: to convey the magnitude of these underlying threats to freshwater sustainability, and to suggest how they might be prevented. We examine “big” threats such as the plight of refugees and the building of huge dams, as well as less dramatic but no less serious ones, such as pollution and the loss of biodiversity. We also examine who controls freshwater, whether growing private control of water supplies is good or bad, and if what we pay for freshwater is fair. We further discuss alternative ways of providing freshwater, including desalination and wastewater recycling, and whether they can equitably slake our planet’s thirst. Finally, we reflect on whether access to freshwater can be thought of as a basic human right: there is certainly no debate that it is a fundamental human need.

Four principles guide our analysis. First, the world’s freshwater is unevenly distributed and unequally used. Growing demands and factors such as climate change will likely worsen this unevenness and inequality. Second, threats to freshwater quality continue to diminish its usability and endanger public health. Third, competition over freshwater is growing because it is a resource increasingly subject to trans-boundary dispute, and increasingly an object of global trade. Finally, when demands for water exceed availability in a given locale, stress and conflict arise, including over proposed methods to make additional water available.

Overview of Global Freshwater

Freshwater is naturally rare. This fact may, at first glance, seem surprising. As shown in figure 1.1, although two-thirds of the earth’s surface is covered by water, most of it is salt water found in oceans. Freshwater comprises some 3 percent of the total, and a large proportion of this is unavailable for use because it is frozen in ice caps and glaciers or locked away as soil moisture.

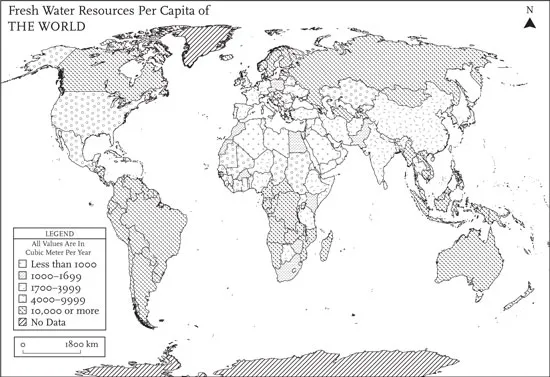

Freshwater is also geographically unevenly distributed. While many Asian, African, and Middle Eastern countries lack abundant freshwater, so does much of Europe (see figure 1.2). The unevenness is caused by climate (which affects precipitation, evaporation, and stream flow), and by geography and geology, including the movement of water under and on the earth’s surface, all of which helps determine when, as well as where, it will be made available.

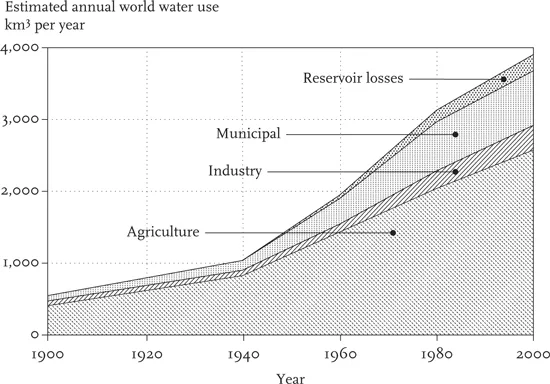

How we use freshwater is also highly variable, both by sector and region. Production of food and fiber currently account for some 70 percent of global water use. Freshwater use closely tracks production of these goods. From 1900 to 2000, global water demands rose six-fold, more than twice the rate of population growth. This is primarily due to agriculture, with urban or municipal use a distant second (figure 1.3). As discussed in chapters 2 and 3, this massive use of freshwater by agriculture Figure 1.1 Distribution of global freshwater poses a number of challenges due to growing competition from cities and other large user sectors (e.g., energy). It also creates numerous water quality problems, including pesticide and fertilizer runoff, as we discuss in the next section.

97.2% = saltwater in oceans

2.14% = ice caps and glaciers

0.61% = groundwater

0.009% = surface water

0.0005% = soil moisture

Source: US Geological Survey

Figure 1.1 Distribution of global freshwater

Figure 1.2 Per capita water availability

Figure 1.3 Global freshwater uses

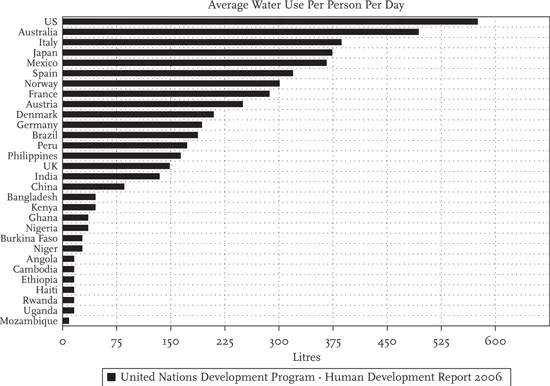

Figure 1.4 Per capita water uses by country

In comparing per capita freshwater usage by country (figure 1.4), a striking fact is that, irrespective of its availability, people in developed countries use comparatively large amounts of water – up to 10 times as much per person – compared to those in the poorest nations. While affluence explains some of this, specific water uses (e.g., agriculture, energy production) are also important. When we combine the uneven distribution of water on the one hand, with the amounts needed for irrigation of crops and by people living in water-poor regions on the other, we can appreciate how scarcity and adverse quality threatens food supply and human health. We can also understand growing calls for global marketing of freshwater.

For example, Canada, a nation of 33 million, possesses some 20 percent of the world’s potable freshwater. Meanwhile, other countries, particularly in the populous and rapidly growing Middle East, are nearly bereft of sufficient freshwater for the needs of their growing populations. Because Canada is potentially a net exporter of water, prospects for developing lucrative exchanges with other countries have been discussed. These opportunities are beginning to arouse awareness of the sustainability problems such trades might generate, as we discuss in chapter 4.5

In countries that are short of water, a different set of responses is arising – fear regarding the security of freshwater supplies is giving rise to efforts to impound greater quantities of freshwater behind massive dams. The goal is to avert shortages, propel industrial development through cheap hydropower, and provide irrigation and flood control to ensure higher rates of food production. Such efforts are taking place in a number of rapidly developing countries, as we will see in chapters 2 and 3, most notably in China, India, Brazil, and Ethiopia.

There is growing consensus among scientists that climate change poses an unprecedented threat to the availability and quality of freshwater. In chapter 2, we more fully examine the implications of this threat for freshwater quality, supply, and use. Here, we briefly discuss some of its implications for availability. In the 1980s, climate scientists’ models indicated that changes in patterns and amounts of precipitation might become important consequences of climate change. Growing evidence, constantly being re-evaluated by scientists from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, US Global Change Research Program, and other organizations, point to worsening conditions occurring sooner than previously expected, especially at the extremes of water availability. Stated simply, areas already experiencing periodic drought or flood are likely to see worse drought and flooding in the future, while uneven patterns of precipitation are likely to become even more extreme.

Despite ongoing debates regarding the evidence for climate change, among those who study water there is a growing conviction that a changing climate is already affecting precipitation – or lack of it. Floods that previously had a probability of 1-in-100 years now appear to be more frequent in some areas – South Asia being one of them. In addition, snowpack – the dominant source of freshwater for the Western US and other regions – is lower in volume and, on average, melts earlier in the spring. This affects farmers (who must plan irrigation schedules accordingly) as well as water utility planners (who will have to anticipate potential decreases of supply in summer).

No summary account can do justice to the magnitude of the changes being forecast. Nevertheless, the following are generally thought to encompass those already occurring: increased drought in mid-latitudes; mountain glaciers melting at unprecedented rates on every continent; earlier vegetation blooms in the spring and summer – with photosynthesis occurring longer during the fall; snow and ice cover decreasing in size and melting earlier, while total annual snowfall amounts in far northern latitudes increase; and, curiously, more water availability in the moist tropics and in higher latitudes (see figure 1.5).6

What all of this means remains anyone’s guess, but it appears certain that, together with the uneven availability of freshwater in many parts of the world, and its rising cost, climate change can only make matters worse. For example, Sana’a may become the world’s first capital city to run out of drinking water by 2025. And even if climate change alone is not the cause of Sana’a’s problems, it is likely a contributing factor. Similarly, while no one can say for certain that the recent Indus floods in Pakistan were caused by climate change, we do know that floods in this region are likely to increase in magnitude if glacial melting in the Himalayas worsens (as climatologists forecast). Thus, we would not be surprised if more levee-busting efforts, like the example discussed earlier, were to occur – worsening the plight of that country’s rural poor.

• Changes in the seasonal distribution and amount of precipitation.

• An increase in precipitation intensity under most situations.

• Changes in the balance between snow and rain.

• Increased evapo-transpiration and a reduction in soil moisture.

• Changes in vegetation cover resulting from changes in temperature and precipitation.

• Consequent changes in management of land resources.

• Accelerated melting of glacial ice.

• Increases in fire risk in many areas.

• Increased coastal inundation and wetland loss from sea level rise.

• Effects of CO2 on plant physiology, leading to reduced transpiration and increased water use efficiency.

Source: Climate Institute, 2010. http://www.climate.org/topics/water.html

Figure 1.5 Effects of climate change on the freshwater cycle

Water Quality, Health, and Environment

Threats to freshwater quality – unlike freshwater availability – are almost solely the result of human activity. Pollution of waterways and groundwater is caused by discharges of sewage from industry, as well as treated and untreated human and animal wastes. In addition to these “point-source” discharges, so-called because they are attributable to a single pipe or point-of-origin, such as a water treatment plant, factory, or power plant – and can often be treated at their source – is non-point “runoff.” The latter cannot be attributed to a single point-of-origin, and is much harder to prevent. Non-point pollution flows off of paved and unpaved urban surfaces, as well as farms and eroded and denuded lands (i.e., those that have experienced clear-cutting of forests or unregulated grazing of livestock). It then finds its way into streams, lakes, ponds, and estuaries.

Bot...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Freshwater: Facts, Figures, Conditions

- 2. Geopolitics and Sustainability

- 3. Threats to Freshwater

- 4. Who’s in Control?

- 5. Water Ethics and Environmental Justice

- Notes

- Selected Readings

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Water by David L. Feldman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Marriage & Family Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.