![]()

| 1 | The People who Could Fly Slavery, Stereotypes, Minstrelsy, and Myth |

Alexanduh say he can fly.

Say all his people in Africa could fly.

(Floyd White, 177–8)

My hands are like a history book.

They tell a countless number of sad, sad stories.

Like a flowing river they seem to have no end.

The cost of survival was high. Why I paid it I will never know.

(Charlie H. Wingfield, Jr., in Marsh, ed., 36)

There are persistent tales of black people who could fly. In the 1930s, for example, a story spread about a man who walked faster and faster until he took off, flying faster than an airplane. Another recounts how a group of turn-of-the-century party-goers overtook a man on the road; he then mysteriously appeared at the barn before the group’s arrival. There were also rumors about shops where wings could be purchased. The old-time spiritual “I’ll Fly Away” was first sung during slavery. Toni Morrison explored this tale in her novel Song of Solomon (1977), which features “flying African children” and ends with the modern-day protagonist flying away.

The most popular tale in this genre is called “The People Could Fly.” In one version of the story, some people who were brought to America on slave ships knew how to fly but had to shed their wings because the ships were so crowded. A mythic figure called High John the Conqueror is said to have flown alongside the ships to gather up the discarded wings. These people subsequently forgot the secret word that enabled them to fly. For African people brought to the American place to perform slave labor, this tale held particular resonance: the ability to fly symbolized the ability to escape their bondage, to “fly away home.” It may now seem like a “dark pre-history,” but it is important to remember that African people were captured, brought through the Middle Passage, and enslaved in America. In Alabama, in Mississippi, in Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas, they lived without citizenship, without any rights at all. They were forced into stoop labor. Stoop labor is work that requires bending your back, like picking cotton or beans.

Whispering the Magic Word

Soon, as the tale goes, the enslaved people grow weary of working long hours in the hot sun. They call on High John to return their wings to them. High John whispers a magic word from their homeland and it is passed down the row. Some people recognized the word and leapt up to High John to reclaim their wings. They flew up and away from the field, flew away to Freedom; but they left behind, sorrowfully left behind, the ones who could not recognize the word. The ones who could not fly had to wait for a chance to run away. The ones who could not fly told their children about the people who flew away to Freedom. And it is from these storytellers and their children that I draw my tale.

Hoping to fly away home

Let me begin with a question: What is a slave? A slave is property, just like your cell phone. Just as you cannot think of your cell phone as having feelings, it was hard for slave owners and others living in the 19th century to think of a slave as a human being. The slave was defined solely by who owned him/her. The owner of the slaves called himself their “master” and thought of them as beasts of burden like a cow or a donkey or a device of convenience like a cell phone. To the Yoruba people in West Africa, a mask is only a piece of carved wood until it is animated by Iwa or life essence. The animated mask becomes a powerful tool in rituals of life, death, and rebirth. To the people who called themselves “masters,” the slave was like that wooden mask, unanimated by an inner life force:

Mask unanimated by Iwa

It come to de time Old Marster have so many slaves he don’t know what to do wid them all. He give some of them off to his chillun. I was give to his grandson, just to wait on him and play wid him. Little Marse John treat me good sometime and kick me round sometime. I see now dat I was just a little dog or monkey, in his heart and mind, dat it ’mused him to pet or kick, as it pleased him.

(Henry Gladney, in Mellon, ed., 149)

Here is another important question: What is the difference between a slave and an enslaved person? If we imagine the Africans placed in bondage as enslaved people, we are forced to see them differently. An enslaved person is a human being who has thoughts, feelings, aspirations, and fears; a human being unwillingly placed in bondage. This is the first distinction it is important to make as we proceed through this cultural companion to African American theater in the US.

As we begin our journey, we stand under the shadow of the Fugitive Slave Act, which was passed in 1850. This diabolical act held that even Africans who had escaped bondage and made it to free states could be captured and returned to their former owners. Under this act, even free-born people, if captured, could be sold into slavery. In the beginning, the English settlers didn’t use slaves. They had indentured servants who were usually poor men and women who wanted to leave England and come to America. So a deal was struck: if you pay for my boat trip, I’ll work for you for four to seven years, but then I’m free. Soon the settlers realized that it was cheaper to have slaves than indentured servants. Slaves could never leave.

The foreign slave trade which brought people from the west coast of Africa to the southern states and forced them into bondage began in the mid-1790s; the importation of slaves into the US was prohibited in 1808. As many as 450,000 Africans were shipped across. Not all of them were enslaved in the southern states. Northern cities such as New York also have a long history of slavery. In 2005–6 the New York Historical Society held an exhibition with an accompanying volume of essays and illustrations, Slavery in New York, edited by Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris. At one time there were more slaves in New York than in Charleston, South Carolina. Other enslaved people were left in the Caribbean, South America, and Central America.

Even after 1808, some slave dealers still illegally brought people from Africa to the United States. But a domestic slave trade also sprang up as slaves were sold from the older and more exhausted lands of the upper South to the newer and more fertile areas of the lower South. Furthermore, children born on American soil were automatically owned by the people who owned their mothers, making for a whole new source of free labor. A five-year-old friend of mine, upon hearing these facts, told me in shock: “You can’t own people!” – but in 1850, in the United States, sadly you could.

History continues to conceal the humanity of the person trapped in slavery. The story of slavery in this country has been told in many voices, from many vantage points, but rarely from the point of view of those who lived through it. How, then, can one learn about the enslaved person’s life in bondage? It is hard to believe, but thousands of ex-slaves were able to tell their stories in their own words before they died. From them, we are able to learn about slavery from the enslaved person’s point of view. As John Little, a fugitive slave who had escaped to Canada, said in 1855: “’Tisn’t he who has stood and looked on, that can tell you what slavery is – ’tis he who has endured” (in Yetman, ed., repr. 2000, 1). Not everyone found it easy to tell these stories: “Lots of old slaves close the door before they tell the truth about their days of slavery” (Martin Jackson, in Mellon, ed., 225).

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, various government agencies initiated work programs across the country to provide jobs for the unemployed. The Library of Congress supervised the programs conceived for jobless writers. The Federal Writers’ Project, for example, culminated in a collection of black folk histories. Field workers were sent out to interview blacks who had lived under slavery. The project yielded first-hand accounts of such experiences on an unprecedented scale. In time, these oral histories came to be published in a wide variety of books by many different authors, extracts of which are quoted below.

The oral histories taken down in the 1930s paint an unbelievable picture. Little children were told that the stork brought the white babies to their mothers, but that the slave children were all hatched out from buzzards’ eggs. And the children believed it was true. (Yetman, ed., repr. 2002, 39). Delia Garlic, one of the elderly women who remembered slavery, told of the grief when people were sold like cattle:

Babies was snatched from their mothers’ breast and sold to speculators. Chilluns was separated from sisters and brothers and never saw each other again. ‘Course they cry! You think they not cry when they was sold like cattle? I could tell you about it all day, but even then you couldn’t guess the awfulness of it.

(in Hurmence, 1994, 99)

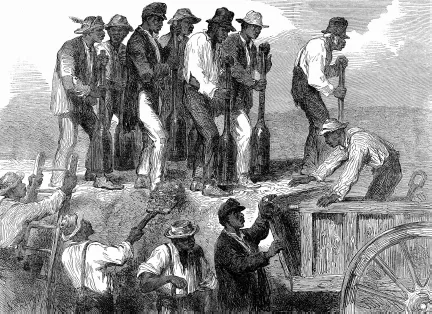

Some stories describe where these people lived: “The slave houses were called the quarters, and the house where Master lived was called the Great House. Our houses had two rooms each, and Marster’s house had twelve rooms” (Mary Anderson, in Yetman, ed., repr. 2000, 15). Others describe food and clothing:

Didn’t have much to eat. Well, they give the colored people an allowance every week. A woman with children would get about a half-bushel of meal a week; a childless woman would get about a peck and a half of meal a week. They get some suet and a slice of bread for breakfast. For dinner they’d eat ashcake baked on the blade of a hoe. The men on the road got one cotton shirt and jacket.

Mourning woman

Men going to work in the field

If you was working they’d give you shoes. Children went barefooted the year around.

(Elizabeth Sparks, in Hurmence, 1994, 29)

They tell of the hard work: “Oh lordy! The way us niggers was treated was awful. Master would beat, knock, kick, kill. He done ever’thing he could cept eat us. We was worked to death” (Charlie Moses, in Mellon, ed., 80). About the cruel beatings: “Folks a mile away could hear dem awful whippings. Dey wuz a turrible part of livin” (Delia Garlic, in Mellon, ed., 244). Of never being able to visit loved ones on other plantations or go anywhere without a pass:

We had one slave there on the plantation that Maser could not do anything with in the way of keeping him at home. When night come, he had him a girl that lived over on another plantation joining ours, and that Negro would go over there. Just as soon as Maser got to bed, he would get up and slip off over to see his girl. So Maser, he finally got him some chains and put them around that Negro’s legs. But then, he would get him a pole to hop around on, and he would get over there some way to see his girl. Maser, he would not be outdone, so he fixed that Negro a shed and bed close to a tree, there on the plantation, and chained his hands and feet to that tree, so he could not slip off to see his Girl.

(Polly Shine, in Mellon, ed., 242)

Among those to tell of the dreaded “patty rollers” is William McWhorter: “I clare to goodness, patterollers was de devil’s own hosses” (in Mellon, ed., 140). Another is Julia Brown:

We wasn’t allowed to go around and have pleasure as the folks does today. We had to have passes to go wherever we wanted. When we’d get out there was a bunch of white men called the “patty rollers.” They’d come in and see if all us had passes, and if they found any who didn’t have a pass, he was whipped, give fifty or more lashes – and they’d count them lashes. If they said a hundred, you got a hundred.

(in Yetman, ed., 2000, 47)

The people who could not fly were not only forbidden to speak their own languages, but forbidden to learn to read or write the language of their captors. The slave owners believed that reading and writing makes a person unfit to be a slave forever (Meltzer, ed., 1964, 60). As Jacob Branch put it: De War comin’ on den and us darsn’t even pick up a piece of paper. De white folks didn’t want us to learn to read for fear us find out things (in Yetman, ed., 2000, 41).

Many slaves suffered forced marriages and rape:

Plenty of the colored women have children by the white men. She know better than to not do what he say. They take them very same children what have they own blood and make slaves out of them. If the missus find out she raise revolution. But she hardly find out. The white men not going to tell and the nigger women were always afraid to. So they just go on hopin’ that things won’t be that way always.

(W. L. Bost, in Hurmence, 198...