![]()

1

Introduction

When people are surveyed on how much alcohol they have consumed during the past week, they commonly underestimate their consumption. This they do not because of the direct effects of alcohol, but because they tend to forget some of the occasions when it was consumed, as they form part of their daily lives. If you were asked how many markets you have been involved in over the past week, could you give the correct answer? This depends on what we mean by “market,” but we can agree that there are many, and it is likely that you would leave out a few of them.

Although markets have not existed since the dawn of humankind, and much of social life takes place outside markets, few will have failed to notice that markets have become central in our everyday lives. If you are living in the UK, Germany, China, or the USA, you, and your activities, are embedded in markets. Children are born into a lifeworld in which markets are taken for granted. It does not take long before they start to play “shop.” Markets have over time penetrated other areas of life, as is manifested by the introduction of life insurance and its accompanying markets. This penetration of market activities into various spheres of our lives means that we have the opportunity to make a choice, but it also means that we have to make choices. Markets have created wealth but they are also part of the reasons for the emergence of economic crises. Let us begin by looking at how markets are related to one another.

Markets not Market

Markets do not come in isolation, but together. The reason is that markets are embedded in one another. Let us take one particular consumer market that we all know as our point of departure and see where it leads us. When you buy a pair of trousers in a local store, the firm from which you buy the pair of trousers competes with other fashion stores by offering different price and fashion/quality levels. The money you use for the purchase is transferred from you to the firm selling the garment, perhaps using a credit or debit card. The card is issued by a bank, and banks compete with other banks to have customers’ savings and deposit accounts, but they also compete with each other for the capital they need to lend to customers and firms. The bank holds money, which is issued by the state – money which is traded in currency markets, around the clock, all over the world. The plastic card is issued by a company that competes with others to offer its services to banks. Firms that employ labor need capital to get off the ground, to invest, and to give credit, and to obtain capital they may take part in different investment markets. Furthermore, production of garments is today a global affair, largely coordinated in markets, populated by buying firms in some countries and suppliers in others, with much lower cost of labor.

Although it is possible, no firm controls the entire garment production chain, which also includes, for example, food for the workers and many other suppliers who may not be directly involved in the production of the garments. The relationship between the fashion firm and its suppliers who manufacture the trousers is established across a market, and it is typical in this market that buyers are located in developed countries, and manufacturers are spread across the globe in less developed countries. The competitors that a manufacturer in India faces can be firms in the same industrial district, but it could also be producers in China or Mexico.

The manufacturing supplier operates in several markets. It buys input material, such as zippers and fabrics, from firms or agents of firms in different markets. The goods have to be shipped and insured, which involves actors who operate in yet other markets. The fashion firm and its suppliers operate in different labor markets. Some of these may be global and others extremely local, and in some stages of production – for example, among suppliers of the garment manufacturers, or even among the suppliers’ suppliers – we can be almost certain that the economy touches on “informal” or “black” markets. The firm that washes the garments before they are shipped may, for example, have suppliers who employ illegal immigrants.

The questions to be addressed

We experience the “market economy” directly and indirectly on a daily basis. Its complexity, however, is often hidden in the wheels within wheels of relations between markets, hierarchies, and networks. A whole range of concrete questions must be addressed if we are to better understand and explain this complexity. For example, how come sellers (and buyers) on the stock exchange are anonymous, whereas sellers in a consumer mass market are known as brands? How is it that markets rather than the activities of peddlers or fairs have become the dominant form of exchange? Can one have capitalism without markets? What are the conditions for black markets? How come some objects are traded in markets and not others?

There are also a number of more theoretical questions which researchers must pose if we are to understand markets. How is order achieved in markets? What roles do the offers, social structure, and culture of the market play with regard to order in the market? Where do markets end? What other forms of economic coordination are possible as alternatives to the market? The over-arching question is as trite as it is tricky: what is a market? We shall now attempt to provide a definition, upon which the rest of the book will rest.

Market Definition

This and the following section will deal with the core of markets and, although they are dense, we will continue to discuss these central issues at length and in detail in the chapters to come. A market is a social structure for the exchange of rights in which offers are evaluated and priced, and compete with one another, which is shorthand for the fact that actors – individuals and firms – compete with one another via offers. This definition covers the market as a place, as well as markets as an “institution.” This connection is observed not only if we trace the phenomenon – as we shall do in chapter 3 – but also in its Latin etymology, mercatus, which refers to trade, but also to place. Another notion, forum, should also be mentioned. It refers more specifically to place and market place. Both, however, refer to public activities. Each market usually has a name, which normally refers to what is being traded – for example, the market for military aircraft – but, as we will see, the product is not necessarily the ordering principle of the market. Other markets, and their names, are connected to a specific place, such as Spitalfields market in London.

Like other definitions, this market definition is based on the life-world and its bed of taken-for-granted behavior, institutions, and propositions which represent and enable all kinds of social relations. What we shall concentrate on, however, is, as a first step, the essential market elements that constitute the definition. Only then shall we look at the three equally necessary prerequisites which, in contrast to the elements of the definition, may be solved in different ways. When the definition and the market prerequisites are taken together, we have a good view of what makes markets different from other social formations.

Elements of the market definition

The rest of the book assumes that structures are the result of human activities which have become “coagulated,” so that they are, in relative terms, stable over time. Fundamentally, we can talk of a structure because of actors’ shared practices and/or cognitive frames. The notion of structure thus accounts for the fact that a market has extension over time. The market structure is constituted by the two roles, buyer and seller, each standing on one side of the market, facing the other. This means that a market implies a record of actual transactions and not merely potential transactions. The two roles have different interests (Swedberg 2004): “to sell at a high price” and to “buy at a low price” (Geertz 1992: 226). It is only because of actors’ interest in trading that there can be a market (Swedberg 2003). In a market, actors get something in return for what they give up; this is the generic buy-and-sell relationship. A market is characterized by “voluntary” and peaceful interaction (Weber 1922: 383; 1968: 17), and this follows from the fact that property rights – that is, a form of ownership based on socially recognized economic rights (Carruthers and Ariovich 2004: 30) that fixate the underlying assets – are accepted. The property rights that actors exchange must be recognized; if not, we must either speak of robbery, if one party simply takes everything, or gift giving, if one party gives without getting anything in return. Property rights, moreover, must be possible to enforce in all kinds of trading, not just market trading, and this facilitates trade (North 1990).1

To accept property rights is not to deny the struggle (Simmel 1923: 216–32; Weber 1978) inherent in the processes of “higgling and bargaining” (Marshall 1961: 453) between buyers and sellers (Swedberg 1998) in the market, and rivalry between actors on the same side (Simmel 1955: 57). Pure market transactions have a distinct ending, in contrast, for example, to the openness and future orientation of network relations (Powell 1990). Market exchange is a voluntary form of economic coordination in which actors have a choice: they can decide to trade, sell, or buy whatever is seen as a legitimate offer, at the price at which they are offered, but they do not have to. In the past, when one slave owner sold slaves on the market to other slave owners, this – as appalling as it may seem – was as much a market as when children choose which lollipop to buy in the supermarket. As long as the property rights and the right to trade are legitimate, granted by the state or any other force capable of imposing sanctions, if only among those who control the rights, a market can exist. Property rights, of course, are also enforced by means of violence, reputation and status in illegal markets, for example, those controlled by the Mafia (Gambetta 1996). Property rights are often embedded in social custom, which means that they are normally not contested (Hodgson 1988: 147– 71).

With the help of these notions, let us now try to see what falls outside of market interaction. People may be more or less forced to sell goods, and even their organs or children, in a market. This does not necessarily affect the way the market functions. The issue at stake is how illegal and/or immoral actions push (by force) and pull (through the expected “prosperity”) people and their goods into a market, not the question of whether it is a market or not. However, the capturing of slaves in Africa or elsewhere was not a market, as the slaves did not have a choice. That the slave market is characterized by voluntary transactions by the owners of the assets – the slaves – does not mean that participation in the market is a joyful experience for those being traded. In other markets, too, people are sold, for example, players who are traded from one club to another in the National Hockey League or in European soccer. However, these players get a large sum of the costs of transfer, and they decided to be on this market, and seem to know the conditions.

We must, consequently, separate the question of how the offers in the market are made from analysis of the market. As indicated, the objects of trade in markets must not only be of interest to the actors, but must also be morally legitimate objects of market transactions, as Zelizer and others have shown (Zelizer 1979, 1981; Healy 2006). Some objects of trade are “blocked” from being exchanged, such as political decisions (Beckert 2006). Financial markets which, by and large, are seen as legitimate today, have only gradually become so; they were not necessarily legitimate outside financial circles in the eighteenth century, when “financial transactions took place in coffee houses and in the adjacent streets, with traders and customers often chased by the police” (Preda 2009: 60–1). Legitimacy must be separated from the distinction between legal and illegal markets; the market for student apartments in the former Soviet Union was seen by many as morally legitimate, though it was illegal (Katsenelinboigen 1977). Legitimacy as a market condition may appear as tautological, but the important point is to think of the degree of legitimacy a certain market has – some black markets are, under certain conditions, accepted by many, and in other cases by few people; an issue to which we return in chapter 7, which deals with the making of markets. We may conclude that the market as a form of coordination does not, per se, exclude trade of any kind of goods or services. We can thus observe “black” or illegal markets, meaning trade of objects that are not legal to trade.

Trade and markets

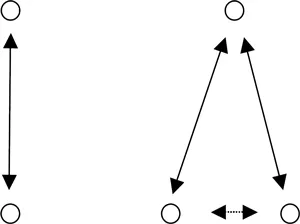

All exchange in markets is trade, but not all trade takes place in markets. In contrast to trade, which can take place between two parties who exchange different kinds of “rights,” markets are characterized by two additional elements, interchangeability of the roles of buyers and sellers, and competition.2 Roles imply the exchangeability of sellers and buyers. Consequently, in a market, in contrast to trade, at least one of the two sides, whether the buying or the selling side, must be composed of at least two actors. Thus, the minimum number of actors required for a market to exist is three; only with three actors can we talk of roles. This is the condition for a comparison of their offers. Comparison is not enough to have a market, however. To speak of a market, as the definition suggests, requires that there is competition between at least two offers (parties), on the one side, for exchange with the other side. It is in this selection process that evaluation takes place in such a way that competing offers can be compared to each other. Competition refers to the relation between two or more actors aiming for an end that cannot be shared between them.3 It must be underlined that competition is for the benefit of the third party, who enjoys the advantages derived from it – tertius gaudens. It is this actor, for example, a single buyer, who can choose among those who strive to sell their offers, who benefits from the competition, not those who compete (Simmel 1955: 154–62). Figure 1.1 illustrates the distinction between trade and market.

Figure 1.1 Trade and market relations as two forms of economic exchange.

Note: The arrows represent relations between actors, who are depicted as circles.

The difference between trade and market, both of which are instances of economic exchange, suggests that the connotation, already mentioned, of the market as something “public,” or transparent, is important. Competition can be either public or secret. The tertius gaudens buyer may utilize its superior position and let two or more sellers compete publicly so that participants and others know of this, but this may also be secret so that no actor but tertius gaudens is aware of the competition that takes place among the sellers. Moreover, if one side – for example, a single seller – lies to the only existing buyer that there is also another buyer, we have “quasi-competition” since this may cause the only buyer to reveal how much value he would be willing to give the product in a “real” competition. In some cases, we have competition among both sellers and buyers in a market; this is the case in the so-called double auction of stock exchanges.

Public prices are of considerable importance for making markets transparent, and the fact that markets generate transparency is an important aspect by means of which they operate as coordination devices. Competition must not boil down to price competition between homogeneous goods – this is just one special case. Competition can be due to innovation, as in Schumpeterian economics (Nelson 2005: 9), or to virtually any variables which are identifiable with regard to the offer, such as quality, service, or style (Chamberlin 1953).

Prerequisites of Market Order

We have now outlined what a market is by describing its essential char...