![]()

1

Conceptualizing Global Politics

ANTHONY G. McGREW

INTRODUCTION

As the Cold War era of conflict and rivalry fades it is being replaced with an expanding awareness of global independence. This is reflected in the language of contemporary politics which is increasingly suffused with references to global problems, appeals to universal values and visions of a global community. Equally it finds expression in the academic study of politics, most visibly in the fascination with the future viability of the modern nation-state in an increasingly interdependent world system. Certainly the fact that no modern society can insulate itself from the vagaries of the world market, or transnational movements of capital, ideas, beliefs, crime, knowledge and news, seems evidence enough of the emergence of a truly global society. Moreover our everyday existence, as a glance in any kitchen cupboard will confirm, is to varying degrees sustained by a complex web of global networks and relationships of production and exchange of which we remain largely unaware. Because of this, events and actions in one part of the world can come to have significant ramifications for communities in quite distant countries. When Iraq entered Kuwait on 2 August 1990, causing a steep rise in oil prices, the headline in a Coventry paper read ‘Iraq invades Kuwait – bus fares in Coventry set to rise’. More significant than the humorous nature of this headline is the unstated assumption that the paper’s audience readily understood: namely that, in an interdependent world, domestic matters are in some mysterious way partly governed by external factors. As McLuhan remarked many years ago, one of the defining characteristics of the modern age is the developing realization that we live in a ‘global village’ (1969, p. 302). Yet the world still remains organized into over 170 separate nation-states each jealously guarding its national independence. Accordingly, whilst few would doubt that within the Western political imagination there is a widespread belief that the world is becoming progressively more interdependent, the actual evidence warrants a more critical and substantive interrogation. That in part is the purpose of this volume.

CONSTITUENT FEATURES OF GLOBAL POLITICS

The apparent emergence, in the late twentieth century, of an increasingly tightly interconnected and self-conscious global community does not necessarily imply, as some have argued, the arrival of some kind of world society. Whilst the infrastructure of a global social system may be evident, most visibly in the globalization of communications, the media and production, the fact remains that the world is organized into sovereign nation-states. Although historically only a relatively modern phenomenon, the nation-state is today the supreme territorial, administrative and political unit which defines the ‘good community’. National sovereignty and the territorial integrity of the nation-state are jealously guarded, most particularly in the Third World where the struggle to achieve independent statehood is still fresh in the collective consciousness. War and permanent preparation for war, political fragmentation, cultural diversity, and the immense gap between the advanced states and the poorest states remain central features of the contemporary global system. Accordingly, whilst from the vantage point of the affluent West there is a temptation to view the world in terms of intensifying patterns of global interconnectedness, at best this is only a partial and superficial perspective. Nor is there any overwhelming evidence to support the frequently asserted proposition that processes of globalization are precipitating a ‘crisis of the territorial nation-state’ (Hertz 1969). On the contrary, the preponderance of the nation-state as the primary unit in world politics is itself a product of globalizing forces.

What seems somewhat less contentious is the observation that political processes, events and activities nowadays appear increasingly to have a global or international dimension. In an age of rapid communications it is fairly commonplace for political events or developments in one part of the world to impinge directly or indirectly on the political process in quite distant communities. Such linkage is articulated most acutely in crisis situations, like that of the 1991 Gulf War or the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, where distant events come to acquire a powerful hold over domestic politics in scores of nations and where the actions of only a handful of decision makers can have truly global consequences. Yet equally significant, although certainly less sensational, are the enormous transnational flows of finance, capital and trade which bind together the well-being of communities spread across the globe. During the early 1990s, for instance, the virtual ending of coal mining in Wales could be attributed in part to the import of more cheaply produced Australian and South African coal. The interconnection between the local, national and global political economy of coal is a vital element in understanding the decline of the Welsh coal industry. But the globalization of markets is only one, albeit important, determinant of the globalization of political life. Of equal significance is the internationalization of the state itself. In the post-war period especially there has been an enormous expansion in both the numbers and the functional scope of international institutions, agencies and regimes. This expansion has been engineered in part by governments recognizing that, in a highly interconnected world system, simply to achieve domestic policy goals requires enhanced levels of international cooperation. In the post-war period the growth of the welfare state and the intensification of patterns of international cooperation were intimately related. Moreover, the revolution in communications and transport technologies has facilitated greatly the global interplay of cultures, values, ideas, knowledge, peoples, social networks, elites and social movements. That this is a highly uneven and differentiated process does not detract from the underlying message that societies can no longer be conceptualized as bounded systems, insulated from the outside world. How could one possibly account for the contemporary drugs problem in most major cities without acknowledging the role of global networks of organized crime and the global trade in narcotics? In modern society the local and the global have become intimately related.

Writing some years ago Rosenau observed that, in the modern era, ‘Politics everywhere, it would seem, are related to politics everywhere else . . . now the roots of . . . political life can be traced to remote corners of the globe’ (in Mansbach et al. 1976, p. 22). In identifying the globalization of the political arena, as a distinctive feature of contemporary politics, Rosenau articulated what can be observed almost daily, namely the declining significance of territorial boundaries and place as the definitive parameters of political life. Politics within the confines of the nation-state, whether at the neighbourhood, local or national levels, cannot be insulated from powerful international forces and the ramifications of events in distant countries. In the late twentieth century, politics can no longer be understood as a purely local or national social activity but must be conceived as a social activity with a global dimension. This invites abolition of the traditional distinction between domestic and international politics, between the foreign and the domestic. It also demands a certain conceptual readjustment: thinking of politics as an activity which stretches across space (as well as time) rather than as a social activity which is confined within the boundaries of the nation-state, or at the international level as an activity confined to interactions between governments. Such a readjustment is realized in the concept of global politics.

To talk of global politics is to acknowledge that political activity and the political process, embracing the exercise of power and authority, are no longer primarily defined by national legal and territorial boundaries. In the twentieth century there has occurred a stretching of the political process such that decisions and actions in one part of the world can come to have world-wide ramifications. Associated with this stretching is also a deepening of the political process such that developments at even the most local level can have global ramifications and vice versa. Moreover, the stretching and deepening have been accompanied by a broadening of the political process. ‘Broadening’ refers to the growing array of issues which surface on the political agenda combined with the enormously diverse range of agencies or groups involved in political decisionmaking processes at all levels from the local to the global. The concept of global politics thus transcends the traditional distinction between the international and the domestic in the study of politics, as well as the statist and institutionalist biases in traditional conceptions of the political. It also suggests that there is an identifiable global political system and global political process which embraces a world-wide network of interactions and relationships between ‘not only states but also other political actors, both “above” the state and “below” it’ (Bull, 1977, p. 276).

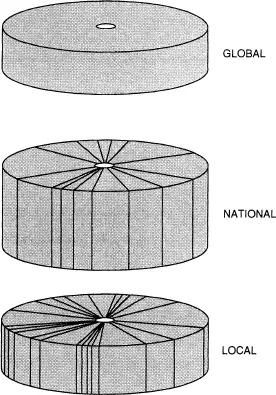

George Modelski (1974) has devised a useful analogy for thinking through some of the distinctions and the connections between different levels of political interaction and activity in the contemporary world. His layer cake model provides a powerful heuristic device for simplifying the complex patterns of political interaction which define global politics. There are, he suggests, three distinct layers of political activity, from the local through the national to the global. To this might be added a fourth, the regional, which sits between the global and the national (see figure 1.1). Each layer, he argues, constitutes a defined political community with its own particular aspirations and needs. Each also embraces an identifiable set of political processes and institutions which exist to facilitate the taking of authoritative decisions. Whilst there are discontinuities between each of these layers, Modelski’s model points to the systemic interdependencies between them; they are porous membranes rather than impermeable barriers to political interaction.

Figure 1.1 Modelski’s layer cake model

Media reports bring to public attention almost daily the evidence of the linkages between these different layers of political activity. When, in early 1991, the German Bundesbank raised domestic interest rates in response to the problems created by reunification, the consequences were felt not just in Europe but globally too. Because of Britain’s membership of the European exchange rate mechanism, such a move meant sustaining high interest rates, exacerbating an already dire picture of rising domestic bankruptcies, unemployment and a housing slump. In the US the same event triggered a run on the dollar, requiring coordinated international action by the world’s major central banks to prevent a further slide which would have had serious ramifications for the American economy. In 1988 the British novelist Salman Rushdie published The Satanic Verses which, because of its characterization of Muhammad, provoked a wave of street protests within Muslim communities across Europe, Asia and the Middle East. Many deaths were reported in these incidents, and the furore led to a Fatwah being issued by the Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran calling for the assassination of Rushdie. This instigated a major diplomatic confrontation between Western governments and Islamic states, resulting in the termination of Britain’s diplomatic relations with Tehran. The Rushdie affair was a clash of cultures and civilizations and played out across the globe, from the street level to the General Assembly of the United Nations. Both of these illustrations give some insight, albeit partial, into the nature of global politics as well as the complex interactions between the layers in Modelski’s layer cake model. Some further systematic exploration of the terrain of global politics is therefore warranted.

Isolating the global layer in Modelski’s model requires us to distinguish between two particular forms of political interaction: interstate or international relations, and transnational relations. Since, as noted earlier, nation-states are the predominant form of political and legal organization in the modern world, the first step towards understanding the dynamics of global politics brings into focus the interactions and relations between sovereign nation-states, or more simply put international relations. In effect, since nation-states are taken to be synonymous with the governments or regimes which rule them, international relations are conventionally understood as the official relationships and diplomatic interactions between national governments, including relations between governments and intergovernmental organizations such as the United Nations. This is the domain of foreign and defence policy and the preserve of foreign ministries and diplomats. It is also a domain which is inherently political because it involves the exercise of influence, power and force by governments in the pursuit of their own national interests. International politics can therefore simply be defined in terms of conflict and cooperation between sovereign nation-states. This definition clearly embraces international organizations in so far as these have become the new arenas within which governments bargain and negotiate with one another (see figure 1.2).

The contemporary world order is historically unique because there now exists a truly global interstate system. In the post-war period, the nation-state has become the dominant form of political organization at the world level. One of the consequences of this globalization of the nation-state form has been the creation, as Bull suggests, of a global political system:

What is chiefly responsible for the degree of interaction among political systems in all continents of the world, sufficient to make it possible for us to speak of a world political system, has been the expansion of the European states system all over the globe, and its transformation into a states system of global dimension.

(1977, pp. 20–1)

Bull’s argument is that the emergence of a global states system, replacing a bifurcated system of states and colonies, has exposed in a very tangible form the ways in which the actions or decisions taken by one government can easily intrude upon the interests and policies pursued by other governments. As a consequence, relationships and issues can be instantly politicized and opposing political coalitions of states readily mobilized. A global states system inevitably entails a high degree of sensitivity among its constituent units to the actions of each other, a situation which Morse (1976) has referred to as strategic interdependence (as opposed to economic, technological or other forms of interdependence). An interesting illustration of this kind of primitive politics amongst states, which exposes the strategic interdependencies between governments, is the case of international economic sanctions against South Africa.

In the mid 1980s the international controversy about how the world community should deal with apartheid in South Africa reached a critical watershed. A significant majority of states within the United Nations desired the imposition of international economic sanctions, whilst many of the more powerful Western states opposed such action. Using bilateral and multilateral diplomacy within many different international forums, such as the UN, the EC and the Commonwealth, black African states, together with their supporters, put international sanctions on the global diplomatic agenda. Those governments pressing for international sanctions recognized that without coordinated international action their own policy objectives could never be achieved. Despite the opposition of the United States and the UK governments, vigilant and concerted political action brought limited success with a combin...