- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

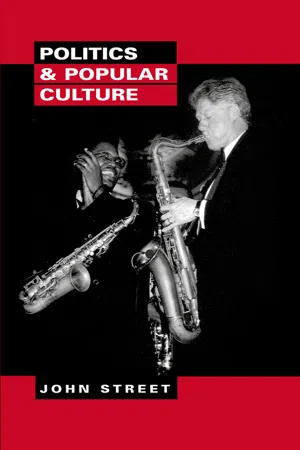

Politics and Popular Culture

About this book

In an age where film stars become presidents and politicians appear in pop videos, politics and popular culture have become inextricably interlinked. In this exciting new book, John Street provides a broad survey and analysis of this relationship.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Politics and Popular Culture by John Street in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART ONE

The Political and the Popular

CHAPTER ONE

Passion, populism, politics

If we were real, then what we saw on CNN was fiction; if it was real, then we must be tricks of the light.Jonathan Raban, Hunting Mr Heartbreak

In March 1981 John Hinckley shot President Reagan in order to impress the film star Jodie Foster. With this single act, politics and popular culture were linked inextricably. Hinckley’s ‘love’ of Foster derived only from her screen image, but it was enough to inspire his attempt to assassinate the President of the United States of America. It might, of course, be reasonable to consign such acts to the realms of clinical psychology, to see them as having no real relevance to either politics or popular culture. But even if the Hinckley case is an extreme one, I still want to claim that it is an example of the intimacy in which politics and popular culture coexist. This relationship is founded on the passions that are generated both by politics and by popular culture.

This connection is not, of course, a simple one. It is not just a matter of popular culture ‘reflecting’ or ‘causing’ political thoughts and actions. Popular culture cannot be treated as a peg on which to hang glib generalizations about the state of the world or about popular feeling. Equally, popular culture does not make people think and act in particular ways. Oliver Stone’s film Natural Born Killers, whatever the rhetoric and panic that it provoked, cannot be treated as the cause of acts of mindless violence.

Following the 1992 British General Election, The Sun newspaper declared that it had secured the Conservatives’ victory. This view was widely shared. It fitted with many general preconceptions about the political power of the tabloid press and of the ambitions of its owners, men like Rupert Murdoch. But such tempting conclusions have proved hard to substantiate. Credible claims have been made for both sides, for those who said the Sun was decisive (Linton, 1996), and for those who said it made no difference (Curtice and Semetko, 1994). The argument between the two sides is couched in terms of separating ‘cause’ and ‘effect’, of distinguishing between the papers as reflections of popular opinion and the papers as shapers of it. But, I want to suggest, the problem may actually lie in posing the debate like this in the first place. Our relationship to popular culture and the popular press cannot be seen simply as a relationship of cause and effect. Instead, popular culture has to be understood as part of our politics.

This is not to deny the political importance of the popular press, but rather to understand it as part of the wider and more complex relationship we have with popular culture. This is to link popular culture directly to our histories and experiences. Reflecting on Elvis Presley’s afterlife, Greil Marcus (1991: xiii–xiv) writes about how Elvis is still part of ‘a great, common conversation… made out of songs, art works, books, movies, dreams; sometimes more than anything cultural noise, the glossolalia of money, advertisements, tabloid headlines, best sellers, urban legends, nightclub japes’. And in this conversation, suggests Marcus, people ‘find themselves caught up in the adventure of remaking his [Elvis’] history, which is to say their own’. This, I think, better captures our relationship to popular culture than any crude notion of culture as cause or as reflection. Popular culture neither manipulates nor mirrors us; instead we live through and with it. We are not compelled to imitate it, any more than it has to imitate us. None the less our lives are bound up with it. This is what Iain Chambers (1986: 13) implies when he talks of popular culture as offering a ‘democratic prospect for appropriating and transforming everyday life’. We might quibble over how ‘democratic’ the relationship is, how much power fans and audiences have compared to that wielded by the producers of popular culture, but Chambers’ key point is about the way we live through that culture. This, it seems to me, is what Jon Savage (1991: 361) means when he records in his diary how it felt to hear punk music in the late 1970s:

The Sex Pistols play for their lives. Rotten pours out all his resentments, his frustration, his claustrophobia into a cauldron of rage that turns this petty piece of theatre into something massive. … The audience is so close that the group are playing as much to fight them off, yet at the same time there is a strong bond: we feel what they feel. We’re just as cornered.

Thirty years earlier, a similar account was given of seeing the film The Blackboard Jungle: ‘I went three times to see that film. Then we’d be dancing coming home, in the middle of the road with all our friends, remembering the footsteps and everything’ (Everett, 1986: 24).

If this view of popular culture is right, then there are important implications for politics. Let me suggest what these might be. Political thoughts and actions cannot be treated as somehow separate or discrete from popular culture. Marcus (1975: 204) writes of Elvis Presley as embodying ‘America’ and its political principles: ‘Elvis takes his strength from the liberating arrogance, pride, and the claim to be unique that grow out of a rich and commonplace understanding of what “democracy” and “equality” are all about.’ The connection between politics and popular emerges too in the way we choose our pleasures and judge our political masters, in the way the aesthetic blends into the ethical. Simon Frith (1996: 72) writes: ‘not to like a record is not just a matter of taste; it is a matter of morality.’ Criticism is often couched in ethical terms. In a review of Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, Pauline Kael wrote in the New Yorker that the film had ‘no more moral intelligence than the Eastwood action pictures’, and that it was a ‘small-minded film’. The core of the problem lay in its hero, Michael, played by Robert De Niro. She complains that ‘he is a hollow figure. There is never a moment when we feel, Oh My God, I know that man, I am that man’ (Kael, 1980: 513, 518 and 519). This is as much a moral judgement as an aesthetic one. This is how the US critic Dave Marsh expressed his dislike of the rock band Oasis: ‘Noel and Liam Gallagher seem, in the end, to be the kind of quasimoralists that Maggie and Ron were, content with their privileges because they think they earned them’ (Marsh, 1996: 71). And just as moral judgements operate within culture, so cultural values operate in politics. We ‘read’ our politicians through their gestures and their faces, in the same way that we read performers on television. One of the key themes in this book is the way in which popular culture becomes – through the uses to which it is put and through the judgements made of it – a form of political activity. An accompanying theme is the thought that contemporary politics is itself conducted through the language and the formats of popular culture.

These themes do not, however, exhaust the relationship between politics and popular culture. The same politicians who exploit popular culture are also engaged in shaping popular culture, and, in doing so, making possible some experiences and denying access to others. Copyright laws, trade policy, censorship, education policy, broadcasting regulations, all these things produce a popular culture that profoundly affects what is heard and seen. And this matters: it matters if people cannot enjoy certain films or books or musics because of the way they live through this culture. The political management of popular culture is, therefore, another key theme.

In an attempt to defend the claim that politics and popular culture are intimately linked, and to explore its implications, this book adopts two perspectives. The first is that of a student of politics, the point of view of someone who wants to understand political processes, political thoughts and political actions. The book is driven by the idea that, if we fail to take popular culture seriously, we impoverish our understanding of the conflicting currents and aspirations which fuel politics. But this book is not just about our understanding of politics. It is also about making sense of popular culture. This is the second perspective, and it derives from one particular question: how do political processes shape the form and content of popular culture? The pleasures and effects of popular culture do not derive straightforwardly from our visits to the cinema or club. Rather they are a consequence of the access we have to popular culture, the opportunity we have to discover its pleasures. And these are the results of political processes. The content and character of popular culture is a legacy of a complex chain of events, marked by the operation of the political institutions and political ideologies that organize them. My approach, and my focus on politics, is not intended to rule out other ways of understanding popular culture, rather it is to emphasize the fact that in thinking about popular culture, we need to recognize the political processes that forge it. They are crucial to determining the importance it has and the stories it tells.

Before looking in detail at the two perspectives, I want to say something about what is meant by ‘popular culture’. In particular, I want to show that even here, in defining popular culture, political institutions and political judgements are inescapably involved.

Defining popular culture

There are countless ways of defining popular culture (see Storey, 1993: 6–17). Many focus upon the means of its production, distribution and consumption. Popular culture is a form of entertainment that is mass produced or is made available to large numbers of people (for example, on television). Availability may be measured by the opportunity to enjoy the product or by the absence of social barriers to enjoyment of it (no particular skills or knowledge are required; no particular status or class is barred from entry). The implicit contrast in this definition of popular culture is to be made with another form of culture: high culture, which is more exclusive, which is less accessible both practically and socially. Chambers (1986: 12) expands upon this distinction:

Official culture, preserved in art galleries, museums and university courses, demands cultivated tastes and a formally imparted knowledge. It demands moments of attention that are separated from the run of daily life. Popular culture, meanwhile, mobilizes the tactile, the incidental, the expendable, the visceral. It does not involve an abstract aesthetic research amongst privileged objects of attention, but invokes mobile orders of sense, taste and desire.

The same contrast can be made between plays in the theatre and television soap operas, between the novels of John Grisham and those of Jeanette Winterson.

Although there is an appealing formality about defining popular culture in terms of the mechanisms that organize its production and consumption, it raises problems in its failure to say anything about the character of the culture itself. What this means is that a play that is seen by a few people off-Broadway or in London’s Royal Court Theatre would not be popular culture in this setting, but were it to be transmitted on a major television channel at peak hours it would become popular culture. In the same way, a novel’s status as popular culture is defined by its sales rather than its style. To avoid these problems, other definitions resort to a more explicitly evaluative approach, focusing on style as much as sales. Here a work of opera, by virtue of the demands it makes upon listener and performer, is deemed to be ‘high’ culture, irrespective of the number of people who see or hear it. This definition of popular culture is established by references to styles and genres of cultural activity. Rock is popular culture, opera is not. Popular (or ‘low’) culture is defined by the fact that it appeals physically (as dance) rather than cerebrally (as contemplation). Other definitions again dwell upon the role and character of the audience, the way it is formed and addressed. This allows distinctions to be made within cultural forms, so that rock that is aimed at (or attracts) a small audience may not count as popular culture; or Beethoven’s symphonies may be popular culture, while his string quartets are not; or Chopin may be popular culture while Stockhausen is not.

It will be immediately apparent that none of these attempts to define popular culture are altogether successful. In the first instance, they are not consistent with each other. For example, popular culture defined by its form (for example, pop music) can clash with the intuition that ‘popular’ also means ‘liked by a large number of people’. Classical music can be ‘popular’ (for example, Pavarotti, Vanessa Mae or Michael Nyman); and some pop music may command a very small audience. Similar problems emerge in using evaluative criteria: can we make sensible and useful distinctions between the songs of Rosanne Cash, Elvis Costello, Ma Rainey, Stephen Sondheim and Benjamin Britten? Terms like ‘complexity’ or ‘sophistication’ are unlikely to get us far, since they can be applied, albeit in different ways, to music in any genre (see Middleton, 1990).

It is from within these confusions that the politics of ‘popular culture’ begin to emerge. Each of the competing accounts is underpinned by a set of political judgements which implicitly separate high from low culture, the elite from the popular. Each definition, by its nature, entails selecting particular cultural forms from amongst others, and making evaluations of their worth. It is not, of course, that such judgements can be avoided, only that they tend to be made implicitly, disguising their underlying values. All definitions of popular culture encode a set of political judgements, or, if acted upon, a set of political consequences. To describe something as popular culture is, for some, to suggest that it is less worthy than other forms of culture. And one implication of this will be to devote fewer resources to it or accord it less status. Only ‘high’ culture is supposed to require state support, because it is deemed to be worthwhile but unable to sustain itself through the market. Equally, to call something popular culture may be, from another point of view, to see it as representing a democratic voice. So, for example, Stuart Hall (1981: 238) sees definitions of popular culture as being juxtaposed to some notion of the ‘power bloc’. Popular culture is defined against dominant culture. These two different definitions of popular culture derive from different political positions. Their differences emerge in the way they identify ‘the people’ and in the way people relate to popular culture. This contingent view of popular culture chimes with Morag Shiach’s (1989: 2) observation that the definition of popular culture is never settled, but is the product of a ‘complex series of responses to historical developments within communications technologies, to increased literacy, or to changes in class relations’. If what we mean by popular culture is conditioned by history, by ideology and by institutions, and if these also affect people’s relationship to popular culture, then we need to look more closely at how popular culture can engage with politics, and vice versa. We need, in short, to return to the two perspectives that I referred to earlier.

Perspective 1: from popular culture to politics

What I want to do here is to sketch briefly the ways in which popular culture seems to engage with politics, the way its pleasures are linked to political thoughts and actions. Think of the way we respond to favourite films or songs or television programmes: the way we laugh and cry, dance and dream. Popular culture makes us feel things, allows us to experience sensations, that are both familiar and novel. It does not simply echo our state of mind, it moves us. Simon Frith (1988a: 123) once wrote: ‘Pop songs do not “reflect” emotions … but give people romantic terms in which to articulate their emotions.’ And in articulating emotions, popular culture links us into a wider world. Part of the pleasure of soap operas is their endless playing out of everyday moral dilemmas, posing questions and suggesting answers to our worries about what we should do. Here is the voice of a woman explaining the pleasure of watching TV soaps: ‘I go round my mate’s and she’ll say, “Did you watch Coronation Street last night? What about so and so?” … We always sit down and it’s “Do you think she’s right last night, what she’s done?” Or, “I wouldn’t have done that,” or “Wasn’t she a cow to him?”’ (Morley, 1986: 156). The vicarious thrill of seeing people behaving badly is animated by our sense of what is right and our understanding of the urge to do wrong. These tensions are not just a matter of private morality; they also extend into our public lives. This, for example, is how some writers have understood the success of film noir of the 1940s. Films like Double Indemnity touched upon the anxieties that confronted a post-war world. George Lipsitz (1982: 177) argues that ‘The popularity of the film noir scenario in postwar America represents more than a commercial trend or an artistic cliché. In its portrayal of a frustrated search for community, film noir addressed the central political issues of American life in the wake of World War II.’ Often this anxiety focused, in such films as The Lady from Shanghai, on male fears about the new social mobility enjoyed by women as a consequence of wartime demands (Chambers, 1986: 101). That popular culture can articulate such thoughts is not merely a matter of academic interest. It can have direct, political consequences. In nineteenth-century France the café singer Thérèsa was immensely popular, but her popularity was seen as subversive and threatening. ‘People believed’, writes T. J. Clark (1984: 227), ‘that Thérèsa posed some sort of threat to the propertied order, and certainly the empire appeared to agree with them. It policed her every line and phrase, and its officers made no secret of the fact that they considered the café-concert a public nuisance.’

Popular culture’s ability to produce and articulate feelings can become the basis of an identity, and that identity can be the source of political thought and action. We know who we are through the feelings and responses we have, and who we are shapes our expectations and our preferences. This sort of argument is advanced by Frith and Horne (1987: 16), who begin by claiming that identity is a founding aspect of politics: ‘People’s sense of themselves has always come from the use of images and symbols (signs of nation, class and sexuality, for example). How else do politics and religion, and art itself work?’ And they go on to argue that identity is itself a product of our encounters with popular culture: ‘We become who we are – in terms of taste and style and political interest and sexual preference – through a whole series of responses to people and images, identifying with some, distinguishing ourselves from others, and through the interplay of these decisions with our material circumstances (as blacks or whites, males or females, workers or non-workers)’ (Frith and Horne, 1987: 16). Behind this argument is the thought that, if politics is the site within which competing claims are voiced and competing interests are managed, there is an important question to be addressed: why do people make such claims or see themselves as having those interests? The answer is that they are the consequence of us seeing ourselves as being certain sorts of people, as having an identity, which in turn establishes our claim upon the political order. These identities emerge in relation to the ways in which nations are defined in their rituals and pageants, in their sporting contests, in their daily newspapers. The press in particular is a crucial actor: in the divisions that get drawn between ‘us’ and ‘them’, whether within countries or between countries. There is an endless attempt to locate people in order to tell stories about them and to provide explanations for their behaviour.

The constant stream of representations in popular culture only paints part of the picture. It matters what people do with the barrage of images and identities. This is revealed in people’s passionate investment in popular culture (representations matter little if no one cares about them). The sports fan is perhaps the most obvious example. Consider this description of Ital...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Part I The Political and the Popular

- Part II Governing Global Culture

- Part III Political Theory/Cultural Theory

- Bibliography

- Index