![]()

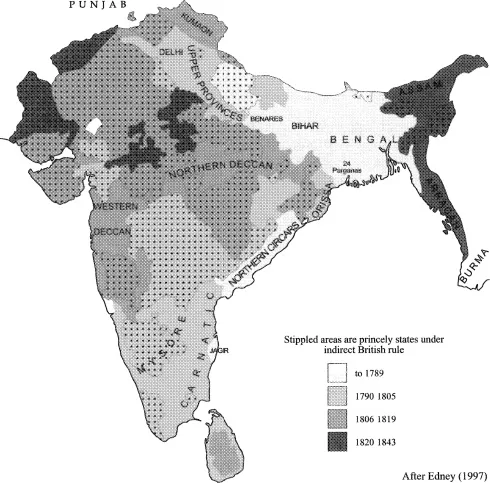

Map 1: Territorial growth of the East India Company, to 1843

Source: Adapted from Edney (1997), p. 20

![]()

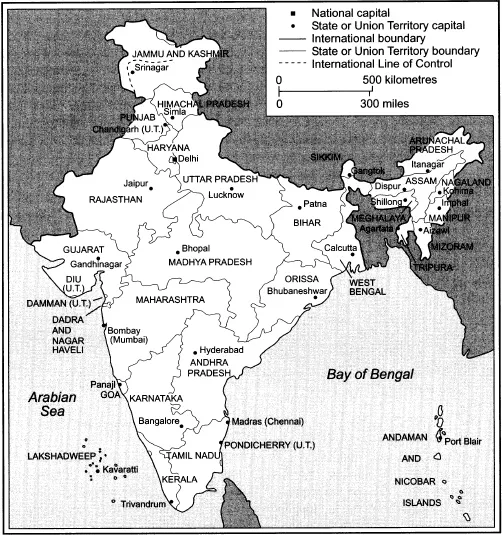

Map 2: Contemporary India

![]()

Preface

‘The Bombs Exploded Underground But The Shockwaves Are Global’… ‘Jubilant India Shrugs Off World Disapproval’… ‘Explosion of Self-Esteem …’: these were some of the headlines in British newspapers after India’s triple nuclear test on 11 May 1998 at Pokhran in Rajasthan. This first test was followed two days later by a further pair of explosions. The world was outraged. Indians, mostly, were delighted. ‘There is a tremendous feeling of pride’, said one of the country’s leading industrialists. ‘With a simmering feeling that they have been pushed around too long, Indians are hopeful that the tests will grant them the recognition that they have long craved’, wrote the local correspondents of London’s Financial Times. Later in the year, in its Annual Country Report on India, the same distinguished newspaper declared that:

By default and design in equal part, India’s economic, political and strategic place in the world suddenly looks vastly different… Who, for example, would have forecast that India’s likely growth rate this year of 5 per cent of GDP would make the country one of Asia’s best performers?… No-one, likewise, correctly forecast that the Bharatiya Janata Party, installed six months ago as the head of a fractious coalition government, would so suddenly and dramatically alter India’s global strategic relations, as it did by detonating five nuclear test blasts and claiming status as a ‘nuclear weapons power’.1

The fact that no one forecast India’s nuclear tests in May 1998 is both a measure of the suddenness of the tests, as the correspondent of the Financial Times surmised, and a reflection of the prevailing ignorance about the country in the 1990s. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is widely known to be associated with Hindu nationalism, or ‘Hindu fundamentalism’ as it is sometimes described, and to have been closely involved with – if not actually responsible for – another critical event in India’s recent history: the destruction by Hindu militants of an old mosque at Ayodhya, in the north Indian State of Uttar Pradesh, in December 1992. But a little more knowledge would have told that the ideological father of modern Hindu nationalism, Veer Savarkar, long ago raised the rallying cry that Indians should ‘Hinduise all politics and militarise all Hindudom’ (cited by McKean 1996: 71). Later, in an address, he exhorted high-school students to bring the ‘secret and science of the atom bomb to India and to make it a mighty nation’ (p. 89). India’s nuclear tests were long foretold,2 and the BJP, in spite of its electoral dissimulations, had never really made any secret of its militant intentions. Pokhran showed just how far the project of ‘militarising Hindudom’ has been taken, just as Ayodhya showed that Savarkar’s call to ‘Hinduise all politics’ has not been ignored.

The story that we tell in this book is not just an account of ‘the rise of the BJP’, however, or of Hindu nationalism, though these both have an important place in our narrative. Our purpose is to tell the story of India’s contemporary history so as to explain how and why it is that the country has changed so much. For we believe that the changes which the Financial Times referred to are not just of passing significance. While the world has hardly noticed, its attention usually focused elsewhere – on the dramas of the collapse of the Soviet system, and the conflicts which followed it; on the spectacles of economic growth and sometimes of spectacular collapse in East Asia and Latin America; or on the recurrent wars of Africa and of southwest Asia – Indian society and the Indian polity were changing. These changes, which have indeed been ones both of ‘default’ and sometimes of ‘design’, account for the different place that India is coming to hold in the world. But this is not a book about international relations or defence or foreign policy. Our concern is with the relations of state and society in India and with Indians’ understandings of them, and of themselves, in a country whose importance can no longer be set aside. That this should be so is one sign, perhaps, of the success of the BJP. Certainly it is a marker of change.

Though all countries, all states and nations, are in a sense being imagined and re-imagined all the time,3 India was the subject of a particular, very deliberate act of invention. In December 1946 a group of dominantly upper-caste Indians, many of whom had been educated in English, most of them men, met in the capital city of colonial India, New Delhi, to begin debating what sort of a country theirs was to be in the future. This was the Constituent Assembly, which drew up the Constitution of India that was promulgated in November 1949, over two years after the country had finally won its freedom from colonial rule. We begin, therefore, with an account both of the context in which this assembly met – the India that had been changed if not transformed by two centuries of British rule – and of the ideas and imaginings which influenced its work. The Constitution envisaged that India would have a modern, and therefore secular and democratic state, endowed with the task of bringing about ‘development’ in what was thought to be a poor and backward society. As we argue, the whole enterprise of ‘development’ as it took off in the post-war world owed a great deal to the arguments within the Indian nationalist movement and in the Constituent Assembly. Development was the raison d’être of the modern state and the source of its legitimacy. Much of the rhetoric was splendid, and to read the speeches of some of the brilliant and noble men who were members of the Assembly – the ‘tall and inspiring men’ of the nationalist elite, as Rajni Kothari describes them – is still a source of pleasure and of inspiration. But what we think of as the founding mythologies of ‘modern India’ – a version of ‘socialism’, secularism, federalism and democracy – reflected many compromises and gave rise to much confusion. The modernizing, developmental mission of the new state, too, was in an important sense one that was imposed by an elite which was not notably democratic in its own attitudes or actions, and which had a history of negating expressions of a popular will.

In the second part of the book we give an interpretive account of the shifting politics of India, and of the factors which have shaped these politics at different levels and sites in Indian society, as we narrate the history of India’s developmental state. The story we tell culminates in vigorous attempts to re-imagine the country, its economy and society, in the 1990s. The reinvention which is taking place in contemporary India – which we analyse in greater detail in the third part of the book – is different from that which took place in the Constituent Assembly. It is not a considered process as the earlier invention was, but rather one of struggle and negotiation. Indeed it has come about partly by default, as a result of the failings of the modernizing mission of the Nehruvian state. These have created spaces for the reforming ambitions of certain economists and politicians, inspired by economic neoliberalism, and for the politics of Hindu nationalism. But there is ‘design’ there too. The arguments for economic reform had been nurtured for a long time by economists such as Jagdish Bhagwati and T. N. Srinivasan, who stood outside the centre-left mainstream of Indian economics, before a particular conjuncture in 1991 provided an opportunity for the implementation of their ideas. The ‘design’ of Hindu cultural nationalism – the establishment of a ‘Hindu state’ – has an even longer history, going back to certain of the reform movements of the nineteenth century. The Hindu nationalists played an important part in the struggle for freedom from colonial rule, but their place and their influence was denied during the ascendancy of the modernizing nationalist elite. Their erasure from the official history was reflected not only in their absence from a popular representation like Richard Attenborough’s famous film Gandhi, but also in their neglect – until the last few years – by most academic social scientists. Their kind of politics did not fit well into the models and the theorizing of mainstream social science. But all the while the persistent activity of what should probably be described as the most effective ‘grass-roots’ organization to which India has given rise, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, nurtured both the ideas and the organizational base for Hindu nationalism. The ideological gap which was left by the earlier nationalist elite’s failure – or unwillingness – to engage with the mass of the people, except in a paternalistic or modernizing mode, was partly filled in the 1990s by the ideology of Hindutva, while the failures of India’s bourgeois politicians left a vacuum into which Hindu nationalism has expanded. Now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Bharatiya Janata Party, as the political wing of the Hindu nationalist ‘family’ of organizations (the Sangh parivar), holds pole position in India politics.

We describe both economic liberalization, and Hindu nationalism, with their sometimes contradictory but often surprisingly complementary agendas for the reinvention of India, as ‘elite revolts’. Both reflect and are vehicles for the interests and aspirations especially of the middle class and higher-caste Indians. But we emphasize the plurality of these ‘revolts’, for though the problems of collective action amongst the elites may be less severe than those which affect the politics of subordinated classes, India’s elites are heterogeneous, and there are important conflicts of interest and aspiration amongst them. And the reinvention of India by Hindu nationalism will finally be constrained, we believe, because its organic conception of the Hindu nation fails to convince the many in Indian society who have long been the objects of caste, class and gender oppression, and who have sometimes benefited from state-sponsored processes of secularization or economic development. The designs of the Hindu nationalists and of the economic reformers are opposed by a diversity of social and political movements which are part of another long history, that of resistance to the established order by those who have been the objects of oppression. Already in the 1870s in Maharashtra, a Non-Brahman leader, Jotirao Phule, had founded an organization, the Satyashodhak Samaj, which in 1889 published a paper proclaiming: ‘We do not want the National Congress because it does not represent the interests of the people’ (cited by O’Hanlon 1985: 284). Movements from below like Phule’s were successfully silenced by the nationalist movement. But they did not go away, and they have been emboldened by the spaces for democratic politics which have opened up, slowly and unevenly, since the introduction of universal suffrage. In India now, in addition to the authoritarian, homogenizing aspirations of Hindutva, there are popular mobilizations with emancipatory objectives, and some others – notably those of the ‘Backward Castes’ – with designs on the state. The reinvention of India that is going on is a struggle, not a planned process, and we conclude by tracing out the lines of struggle and their relationship to the design for India mapped out in the Constituent Assembly.

This is not a ‘theoretical’ book, though we believe that it is sensibly informed by theory and part of our purpose has been to trace and understand ideas about Indian society and the state. We have no ‘model’, but we do follow Partha Chatterjee and Sudipta Kaviraj – the inspiration of whose words and writings we want particularly to acknowledge – in finding Gramsci’s idea of the ‘passive revolution’ provocative in regard to India’s modern history. India experienced the establishment of parliamentary democracy under a universal franchise without having first gone through an industrial revolution; and the Indian bourgeoisie, though more strongly established than were the bourgeoisies of other former colonies, was far from exercising hegemony at the time of independence. There had been no bourgeois revolution. The bourgeoisie had to compromise politically, therefore, with rich peasants and with other members of India’s ‘intermediate classes’4 – self-employed producers, traders and others employed in services (including some ‘government servants’, who are ‘self-employed’ de facto, as they procure bureaucratic rents) – and it was forced to rely on the bureaucracy for carrying forward India’s development. In this way an expensive and technocratic ‘passive revolution’ was substituted for social transformation, and, partly in consequence, the Indian polity has come increasingly to be dominated by richer farmers and their associates within the growing rural-urban ‘middle class’. The elite revolts of the 1990s and the reinvention of India which they entail – including the increasing importance of regionalism in Indian politics – have been prompted by India’s changing engagements with the global political economy, and by external events, including – notably – the threats perceived in the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. But they are the outcomes, in large part, of struggles around the assertiveness of hitherto subordinated classes, and of struggles amongst these classes, often fought out on lines of caste and community, which have come about as a consequence of the progressive ‘ruralization’ of Indian politics.

Our analysis is unashamedly unfashionable. Though it is necessarily concerned with the politics of identity, it is founded nonetheless on a concern with class formation and the dynamics of accumulation; and in a context in which the economic ideology of neo-liberalism remains influential, and in which ‘post-structuralist’ and ‘post-colonial’ ideas are pervasive, our analysis may be unfashionable, too, in reaching the conclusion that the history of independent India continues to be written around the state and the ‘state idea’.

![]()

PART I

The Invention of Modern India

![]()

1

The Light of Asia? India in 1947

In the mass of Asia, in Asia ravaged by war, we have here the one country that has been seeking to apply the principles of democracy. I have always felt myself that political India might be the light of Asia.

Clement Attlee, 19461

Clement Attlee’s remark about political India serving as the ‘light of Asia’ was probably well intentioned, and in some respects it marked a new beginning in the history of relations between imperial Britain and colonial India. By 1946 it was clear to most observers that India’s independence was not far off, and not many months later a future President of the Republic of India, Dr Radhakrishnan, was quoting Attlee’s remark in favourable terms in the Constituent Assembly. Post-colonial India would be a beacon of democracy and liberty in a world emerging from fascism, war, and Empire. Even so, the irony of Attlee’s declaration would not have been lost on those members of the Constituent Assembly charged with inventing a new India in the years 1946–9. Most Congressmen took the view that Britain, by 1946–7, was bent on destroying the fabled unity in diversity of India, and had succumbed to and fostered the two nations theory put forward by Jinnah and the Muslim League. They were soon proved right. In addition, British rule in India could hardly be described as an experiment in democracy, either in representative or in participatory terms. The British ruled India with the help of local notables, but with little regard for the claims of political citizenship that grew to fullness in Great Britain between 1832 and 1928. India was pivotal to the Empire from which Britain benefited, yet few coherent efforts were made to improve the living conditions or education levels of the majority of India’s households. For most such men and women the light of Asia shone very darkly, if it shone at all.

In chapter 2 we examine the Constituent Assembly’s attempts to invent a post-colonial India which, rhetorically at least, would be everything that British India was not: a democratic, federal Republic of India committed to an ideology of development. Before embarking on this examination, however, it is important that we say something about the state of India in 1947, and that we briefly consider the political and economic legacies of British rule in India. We will also make some preliminary observations on the programmes of the nationalist elites who delivered India from Britain on 15 August 1947.

1.1 The Political Legacies of Empire

When the British left India they left behind them two countries – India and Pakistan – that had been shaped by more than 250 years of economic, political and cultural contact with the English East India Company and the Raj. This is not to say that Indian history during this period was made only by the British, or by Indians reacting to and resisting British definitions of modernity and community. The writings of nationalist, ‘Cambridge school’2 and subaltern historians alike have discredited this sort of imperial history. Nevertheless, the very geography of India in late 1947 pointed up the contradictory and contested legacies of European rule in South Asia. When Nehru was sworn in as the first Prime Minister of India he took charge of a country that was still being carved up by Cyril John Radcliffe, the mapmaker of Partition, and where ambitions for a unitary territory were disrupted by the remnants of French and Portuguese conquests in South Asia (as in Pondicherry and Goa) and the need to integrate 565 Princely States into the new Republic.3 Meanwhile, in divided Bengal, the government had to face up to the tragic legacies of the famine of 1943–4 – a famine caused in no small part by the state’s failure to provide an adequate system of relief to compensate for the lost entitlements of agricultural labourers and artisans.4 To uncover these legacies in more detail, it is useful to review some key moments in the political construction of power in British India, from Company rule to the end-games of Empire by way of the age of high imperialism that peaked around 1914.

Company rule

The British were not the first European power to acquire a base in South Asia, but the English ...