- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The purpose and location of frontiers affect all human societies in the contemporary world - this book offers an introduction to them and the issues they raise.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Frontiers by Malcolm Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

International Relations1

The International Frontier in Historical and Theoretical Perspective

This chapter sets out elements of the intellectual context in which contemporary assumptions about frontiers have developed, with some references to the political processes through which the current international frontier has emerged. Frontier- or boundary-making has been a constantly repeated activity in the course of human history, but the characteristics of frontiers have varied considerably over time. Frontiers between states in post-Reformation Europe more and more resembled one another and became rooted, as institutions, in a common fund of ideas. Ideas of sovereignty, exclusive control over contiguous territory,1 the nation-state and the juridical equality of states in an international society regulated by a voluntary acceptance of international law resulted in the spread of a common understanding of the frontiers of states.

Certain periods have, in retrospect,2 made significant contributions to the ideas on which modern state frontiers are based – the Roman empire for notions of territoriality, the ‘universalist’ doctrines of the Middle Ages which offered an alternative project to the hardened frontiers of the states which emerged in Europe from the fifteenth century onwards, the development of the frontiers of France which prefigured those of the other European ‘nation-states’, the global spread of European notions of the frontier after the colonizing of lands in other continents, and the challenges to the frontier of the sovereign state in the post-Second World War international system. These landmarks in the history of frontiers mark an evolution in terms of stability of frontiers and the complexity of frontier functions.

The Legacy of Rome

Most ancient cultures and civilizations have left little mark on the territorial organization of the contemporary world. Their cosmologies, in which their sense of territory was rooted, are utterly alien to modern secular thought. But the modern international frontier and the related concept of sovereignty owe much to Roman ideas of territoriality, of dominium and imperium, transmitted through the Catholic Church, rediscovered by political theorists of the Renaissance and regarded as useful tools by jurists serving the interests of princes in the early modern period of European history. There are many problems associated with the reception of the Roman private law notion of property (dominium) and public law notion of undivided authority (imperium) in early modern Europe but only the main lines and understandings are relevant here.3

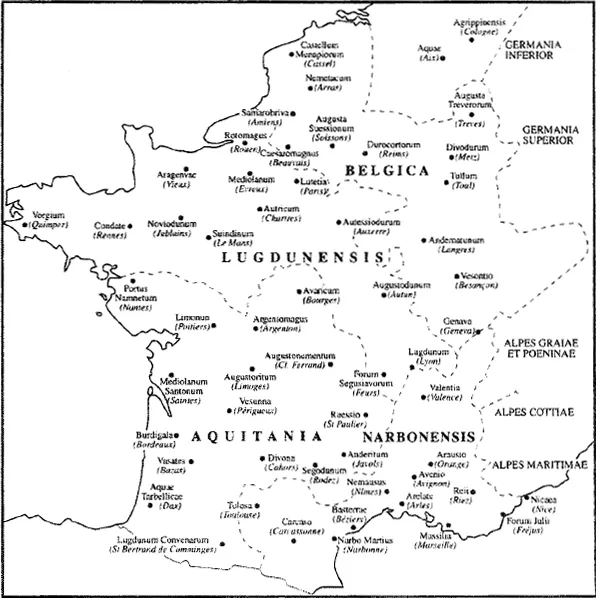

The influential features of Roman law and administration were developed from the first century BC. The relative density of population in Italy, from the period of the Roman Republic (509–27 BC), resulted in settlements being adjacent to one another, without the swamps, forests or uninhabited zones, which characteristically separated many pre-modern societies. As a consequence, clearly demarcated boundaries between settlements in ancient Italy were established (as they were in classical Greece, for the same reasons). When the Romans extended their empire into Gaul, they took this practice of demarcating boundaries with them. Often the old territorial divisions of indigenous peoples were confirmed by stone frontier-markers. The Romans also established a hierarchy of territorial divisions, commencing with the pagus at the base, then the civitatis and, at the apex, the provincia or regio.

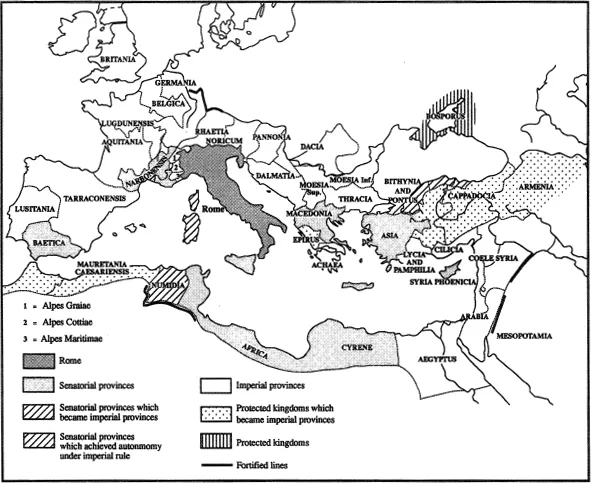

The external frontiers of the Roman empire have seemed to the superficial observer, such as Rudyard Kipling,4 to have been the archetype of the linear defensive frontier, dividing civilization from barbarism. The fossatum of North Africa, the limes of Syria, the Rhine and the Danube, the walls of Hadrian and Antonius (effectively occupied for only twenty years)5 in Britain seem to have this purpose, if the archaeological evidence is viewed through the prism of the nineteenth-century experience of boundary-making. Even a sophisticated historian, Edward Luttwak, asserts that the Romans, like the British in India, sought fixed ‘scientific frontiers’ behind which the legions could defend the empire from external attack.6 However, it seems more likely that they were means of policing the territory through which these great fortifications ran; Roman power and authority were felt by peoples far beyond them.7 The relations between Imperial Rome and neighbouring peoples varied greatly during the centuries and between the different frontiers of the empire.8 But Roman territorial organization – the outer limits of the march of the legions, as well as the internal Roman territorial divisions – continued to mark the social and political landscape long after the empire’s disintegration.

The larger divisions of the empire, such as Hispania, Italia and Gallia, eventually became the territorial basis of the modern state system.9 Some external Roman frontiers left an almost indelible impression. As Fernand Braudel writes: ‘The frontier between the Rhine and the Danube was … a cultural frontier par excellence: on the one side Christian Europe, on the other the Christian periphery, conquered at a later date. When the Reformation occurred, it was along virtually the same frontier that the split in Christianity became established: Protestants on one side and Catholics on the other. And it is, of course, visibly the ancient limes or outer limit of the Roman empire. Many examples would tell the same story.’10 However, the great paradox in modern European political development, analysed by Stein Rokkan, is that the stable and strong states were established at the periphery of the territory of the Roman empire and the old core in Italy dissolved into loosely associated, competing and often warring, civitates.11

Within the territory they governed directly, the Romans were practical administrators who sought clear and comprehensive systems of rules – uncontrolled or unassigned territory was anathema to them. They also attempted to establish clear administrative hierarchies, and this included the hierarchical arrangement of territorial units. The final authority, the imperium, was at the apex of the hierarchy and the modern notion of sovereignty was derived from it. This association of final authority, of hierarchy and of territorial organization was taken over by the Catholic Church in the late Roman empire; the hierarchical system of archdioceses, dioceses and parishes with the bishop of Rome as the source of authority was well established by the fourth and fifth centuries.

The Middle Ages and Universalism

The uniformity of church territorial organization was disrupted by the collapse of the Roman Empire; from the sixth to the eleventh centuries there was a process described as the feudalization of the church.12 However, clarity of territorial organization of the church remained an aspiration. As early as the ninth century all Christians were assigned to a specific parish and subsequently rules forbade them to listen to sermons in other parishes. The great councils of the Lateran, Lyon, Clermont and Dalmatia endorsed canons which made the church more bureaucratic and more hierarchical. They revived the Roman principles of territorial organization for the regular clergy. In this, the church was in advance, in principle if not always in practice, of the feudal secular order.13

Map 1 Roman administrative areas in Gaul

Map 2 The Roman empire at its greatest extent, showing main fortified lines

By contrast with the church, land holding and allegiance in lay society were often highly fragmented. The land of the feudal nobility in the late Middle Ages was often not contiguous; a village could depend on more than one lord; lords could owe allegiance to more than one ruler; manorial courts, royal courts and ecclesiastical courts dispensed customary, statutory and church law to the same populations. Powerful rulers attempted to simplify the complexity of territorial organization in order to strengthen their authority. They initiated accurate record-keeping about land-holding, commencing with the Domesday Book in the late eleventh century in England, followed over a century later by a similar exercise in France.14 This record-keeping was the basis of a new conception of territory in western Europe, which gradually spread to central and eastern Europe.

Several developments were associated with the new conception of territory, such as the institutionalization of secular administration and justice, rudimentary forms of representative assembly to approve taxes and legislation and conceptions of the political order based on more durable and impersonal loyalties than feudal relationships. Genealogy and genealogical myth remained as a basis of claims to authority, but they were first supplemented by others and then replaced – more quickly in western than in central and eastern Europe. Also, the myth of the universal empire, partly protecting and partly subordinate to a universal church, was slowly undermined. With hindsight, there is a sense of historical inevitability about the shift to state sovereignty; but absolute control of territory by rulers recognizing no superior authority was for a long time challenged by various forms of universalism. The core belief of universalism was that some high authority ought to hold sway over the whole of mankind or at least the civilized part of it. This belief came to be regarded as archaic or utopian in post-Reformation, post-Renaissance Europe. But it never entirely disappeared and eventually it took secular form.

Universalism was the philosophical and theological basis of the empire of Charlemagne (800–14) and remained that of the Holy Roman Empire, with diminishing plausibility, for a millennium. Even Charlemagne accepted that there were territorial limits to his empire; his authority neither extended to, nor clashed with, a competing universalism, that of Byzantium and the eastern church.15 Systematic boundary-making within the empire commenced on Charlemagne’s death when the patrimony was divided between his three grandsons at the treaty of Verdun in 843.16 A third universalism emerged after the collapse of Byzantium, the tsar of all the Russias in conjunction with the Russian Orthodox Church. This partnership of throne and altar had more limited success and was eventually identified with an ethno-cultural exclusivity – pan-Slavism.17

These empires had an aspiration to suzerainty over the whole of Christendom but they never came near to achieving it and, despite this pretension, they always treated competing Christian rulers differently from non-Christian rulers. The practice of greater consideration, in diplomatic practices, by Christian rulers for each other survived as a polite gesture towards the belief in the unity and universality of Christendom during the growing secularization of politics of the eighteenth century into the age of European imperial domination of other continents in the nineteenth century. There were, of course, non-European, non-Christian empires, which also aspired to universal authority, emerging in the Muslim world and in China,18 recurring during the successive dynasties which ruled the Chinese empire. These have not had the same influence as the Roman empire over the contemporary state system or over the attempts to overcome the defects of that system through international organization.

The Emergence of the Modern State System

In western Europe during the Middle Ages, the uneasy, sometimes conflicting, relationship between Pope and Holy Roman Emperor allowed the development of polities independent of both – the modern European states. The state system was anchored in the doctrine of the exclusive authority of the state within its own territory, subordinated only to the higher authority of God; states did not recognize the hegemony of any terrestrial ruler or universal church except, in the case of Catholic states, that of the Papacy in narrowly conceived spiritual matters. After the Reformation, according to the principle of cuius regio, eius religio, rulers imposed, where they could, the religion of their subjects.

Universalist thinking inspired by Christian doctrine survived in the new political order in various schemes for universal peace, such as those of the abbé Saint-Pierre and Immanuel Kant in the eighteenth century, and in ultramontane Catholicism which sought to revive the Papacy’s influence over temporal matters by strengthening the Pope’s spiritual authority. Even the late eighteenth-century Anglican conservative Edmund Burke was influenced by universalist thinking when he described Europe as ‘virtually one great State having the same basis of general law’ and that ‘no citizen of Europe could be altogether an exile in any part of it’.19 Universalism took a decidedly secular form during the French Revolution in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 1789 and, more explicitly, in Marxism and in some other forms of nineteenth-century socialist thought. In political practice, those who upheld universalism were of marginal significance, except briefly after the French and the Russian revolutions, faced by the power and willingness of states to repress, and persecute, those who actively sought to put into effect universalist doctrines.

The contemporary international frontier developed as a result of a curious amalgam of universalism and particularist thinking. It is inextricably linked with the emergence of the concept of sovereignty in the theory and practice of European politics from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries.20 Sovereignty was not associated with a particular form of government – as Hobbes expressed it, the sovereign could be ‘the one or the many’ – but it was the basis of all properly established states.

The important implication of this doctrine for frontiers was that they were necessarily exclusive. The absolute nature of the authority exercised by the sovereign over territory and over individuals explicitly denied the possibility of the interpenetration of jurisdictions of the medieval polity in which kings, lords and clergy had autonomous judicial authority in the same territory. A single, supreme and independent sovereign was the hallmark of the state system of modern Europe, although competing authorities were common until the French Revolution of 1789. As far as crossing frontiers was concerned, the right of unimpeded exit for those individuals who had broken no law was admitted, but there was no equivalent right of entry. This right was in the gift of the sovereign, who could impose any conditions on foreigners who sought it; an important exception was made through the development of diplomatic immunity to the representatives of other sovereign powers.

The French Example

Establishing the identity of state-nation-territory, the underlying aspiration of the modern state, has been subject to many interpretations. But the linear frontier was the first requirement to establish this identity. This frontier was a rarity in the Middle Ages because of the virtual absence of continuous lines of fortification.21 But in the late medieval and early modern periods, the kingdoms of western Christendom were virtually compelled to centralize in order to survive. Any weakness of central authority was ruthlessly exploited by internal and external enemies. An alternative model of political development, the city-state, which Braudel has called Europe’s first fatherland,22 showed remarkable vitality in northern Italy and in the Hanseatic towns of northern Europe, but it eventually could not resist the concentration of power in the kingdom-states. As Anthony Giddens has written, the nation-state replaced ‘the city as the “power-container” shaping the development of capitalist societies’.23 France was the great example of a kingdom compelled either to concentrate power or to fragment into a myriad local jurisdictions.

The historical problem, posed clearly by Lucien Febvre at the beginning of the twentieth century, concerns the aftermath of the Middle Ages: ‘… how and why these heterogeneous regions which no divine decree designated for unity … finally came together; this unity, first mentioned by Caesar in describing Gaul as having certain “natural limits”, which was an approximate forerunner of France … How and why despite so many “offers” … despite so many failed initiatives to create Anglo-French, Franco-Iberian, Franco-Lombard or Franco-Rhenish nations, once seen as possibilities...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The International Frontier in Historical and Theoretical Perspective

- 2 Self-Determination, Secession and Autonomy: European Cases of Boundary-Drawing

- 3 Themes in African and Asian Frontier Disputes

- 4 Boundaries within States: Size, Democracy and Service Provision

- 5 Frontiers and Migration

- 6 Uninhabited Zones and International Cooperation

- Conclusion: The European Union and the Future of Frontiers

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index