eBook - ePub

Climate Governance in the Developing World

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Climate Governance in the Developing World

About this book

Since 2009, a diverse group of developing states that includes China, Brazil, Ethiopia and Costa Rica has been advancing unprecedented pledges to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, offering new, unexpected signs of climate leadership. Some scholars have gone so far as to argue that these targets are now even more ambitious than those put forward by their wealthier counterparts. But what really lies behind these new pledges? What actions are being taken to meet them? And what stumbling blocks lie in the way of their realization?

In this book, an international group of scholars seeks to address these questions by analyzing the experiences of twelve states from across Asia, the Americas and Africa. The authors map the evolution of climate policies in each country and examine the complex array of actors, interests, institutions and ideas that has shaped their approaches. Offering the most comprehensive analysis thus far of the unique challenges that developing countries face in the domain of climate change, Climate Governance in the Developing World reveals the political, economic and environmental realities that underpin the pledges made by developing states, and which together determine the chances of success and failure.

In this book, an international group of scholars seeks to address these questions by analyzing the experiences of twelve states from across Asia, the Americas and Africa. The authors map the evolution of climate policies in each country and examine the complex array of actors, interests, institutions and ideas that has shaped their approaches. Offering the most comprehensive analysis thus far of the unique challenges that developing countries face in the domain of climate change, Climate Governance in the Developing World reveals the political, economic and environmental realities that underpin the pledges made by developing states, and which together determine the chances of success and failure.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Environment & Energy Policy1

Editors’ Introduction: Climate Governance in the Developing World

David Held, Charles Roger and Eva-Maria Nag

FOR most of the period since the early 1990s, the locus of action on climate change has largely been in the industrialized world. The 1997 Kyoto Protocol is, for example, the most ambitious international effort to establish quantitative limits on countries’ greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. During the first commitment period, it obliged a group of thirty-seven countries to reduce their emissions collectively to 5 per cent below 1990 levels by 2008–12. Yet this only applied to industrialized states, known as ‘Annex I’ countries in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Developing countries, known as ‘non-Annex I states’,1 were effectively excluded from any binding obligations. Within the industrialized world, the European Union in particular has been at the forefront of efforts to govern climate change. The European Emissions Trading System, the world’s first multinational emissions trading scheme, was launched in 2005, and a range of other Europe-wide climate policies have been enacted since then. Many European states, like the United Kingdom, Denmark and Germany, have also established policies to promote the adoption of renewable sources of energy, created policies to encourage energy efficiency, or implemented national carbon taxes designed to put a price on carbon and abate emissions.

Action in the industrialized world is, of course, not confined to the European continent and the British Isles. Outside of Europe, Japan has created a range of climate mitigation policies, New Zealand operates a mandatory emissions trading system, and Australia now plans to establish one as well. National policies in North America are much less developed and coherent, but individual states, provinces and municipalities in the United States and Canada have taken the lead and created their own climate change policies despite the dearth of action at the national level. California, for instance, has set a goal of reducing its emissions to 1990 levels by 2020 and has established a statewide cap-and-trade system to meet it; Quebec and British Columbia (in Canada) have implemented carbon taxes, while Alberta operates a baseline-and-credit emissions trading scheme; and a number of cities in both the United States and Canada have established climate action plans. Finally, many sub-national governments in North America have also worked together through regional carbon trading schemes such as the Western Climate Initiative and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

Even though the above developments in the industrialized world have been insufficient to meet the challenge of global warming, they have traditionally constituted the ‘frontline’ in the global battle against climate change. By contrast, developing countries since the early 1990s have consistently maintained that they have little obligation to take immediate action. In the international climate change negotiations, they have proven deeply reluctant to adopt binding mitigation targets similar to those adopted by industrialized states under Kyoto. Doing so, they have argued, would reduce the space for economic growth and development, which are viewed as overriding priorities. Further, since currently developed states did not have to curb emissions during their own industrialization experience, it would be patently unfair for developing countries to have to do so, even if this were for the ‘global good’. They should be allowed to emit more in order to meet their legitimate socio-economic and developmental needs. Thus, the domestic climate change policies of most developing countries have traditionally been thought to be much less proactive than those in the industrialized world. While they occasionally took actions that had the side-effect of abating emissions (by reducing energy subsidies, for example; see Reid & Goldemberg 1998), one early review of climate change policies in low income countries by an analyst from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) summed up its findings by explaining that ‘most developing countries are neither prepared to address nor interested in climate change’ (Gómez-Echeverri 2000). Climate considerations have, for the most part, hardly figured in plans for economic development, policymaking has been limited, and those actions that have been taken have often been driven by multilateral and transnational actors from wealthier countries, with little domestic ownership (Olsen 2006).

To be sure, most developing states, especially least developed states, are still unprepared for, if not uninterested in, climate change. Yet, over the past several years, one of the most remarkable developments in the arena of climate change has been the growing number of non-Annex I states that have made unilateral commitments to mitigate emissions within their borders. China has recently pledged in its 12th Five-Year Plan to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by 40–5 per cent from 2005 levels by 2020. Brazil, likewise, now aims to reduce national emissions by 36–9 per cent below its baseline emissions scenario by 2020. Mexico has announced that it intends to reduce emissions by up to 20 per cent from business-as-usual (BAU) by 2020, and plans to reduce emissions by 50 per cent by 2050. South Africa has set a goal of reducing emissions by 34 per cent below BAU by 2020 and by 42 per cent by 2025. Even Ethiopia, after playing a leading role representing Africa in the climate negotiations, has established a target of becoming ‘carbon free’ by 2022. Beyond the elaboration of such targets, however, many developing states have also been creating a welter of more specific plans, programmes and policies for meeting them. These include, for instance, policies for encouraging the use of renewable sources of energy, improving energy efficiency, reducing rates of deforestation and land use change, and raising emissions standards in manufacturing, buildings and vehicles, to name just a few. Some, such as China and South Korea, have even announced plans to establish emissions trading schemes of their own.

Despite these growing commitments, most developing states have not yet adopted more conciliatory negotiating positions at the international level. Many continue to argue that they should not be obliged to adopt binding targets and timetables. Nonetheless, the commitments that developing countries have been making can be seen in the many declarations of Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) that were submitted to the UNFCCC Secretariat after the signing of the Copenhagen Accord in 2009. By the end of 2012, a total of forty-four developing states had submitted NAMAs, in addition to commitments by forty-two industrialized countries.2 NAMAs are, essentially, a set of targets or policies or actions that a country intends to undertake voluntarily in order to reduce their emissions. They do not establish binding international obligations and there are no legal requirements for states to follow through on their promises. Further, NAMAs vary considerably in their level of detail and ambition. Some set out precise quantitative emissions targets, such as those mentioned above, while others simply list actions without specifying their proposed scope and expected impact. Having said this, NAMAs do broadly offer a rough indicator of the growing scale of the commitments developing states have been making. Together, the commitments made by developed and developing countries cover more than 80 per cent of global emissions, and, if delivered, could reduce emissions from BAU by 6.7–7.7 billion tonnes (Stern & Taylor 2010). But, most interestingly, there now appears to be ‘broad agreement’ that the actions that have been proposed by developing countries may do more to reduce future global emissions than those pledged by industrialized states (Kartha & Erickson 2011).

Of course, not all plans are likely to be successful. Developing countries continue to face a number of challenges that make implementation especially difficult. In some countries, targets are also far less ambitious, meaningful and credible than elsewhere. Estimates of the stringency of seemingly ambitious plans have been questioned as well. Some, such as Fatih Birol, chief economist of the International Energy Agency, have optimistically estimated that China’s recent commitment may reduce projected emissions by as much as one gigatonne or 25 per cent of the total world reduction needed to stabilize average global temperature rise at 2 °C (see AFP 2009). Critics of China’s target argue, on the other hand, that its pledge represents nothing of the sort and, in fact, is little more than the continuation of current policies and measures. This is certainly an important matter for empirical investigation and debate. What is undeniable, however, is that there appears to be a new level of interest in climate change in certain parts of the developing world, a host of new unilateral commitments, and, in some places, seemingly ambitious domestic policies and programmes for achieving them. The locus of climate change policymaking appears to be shifting.

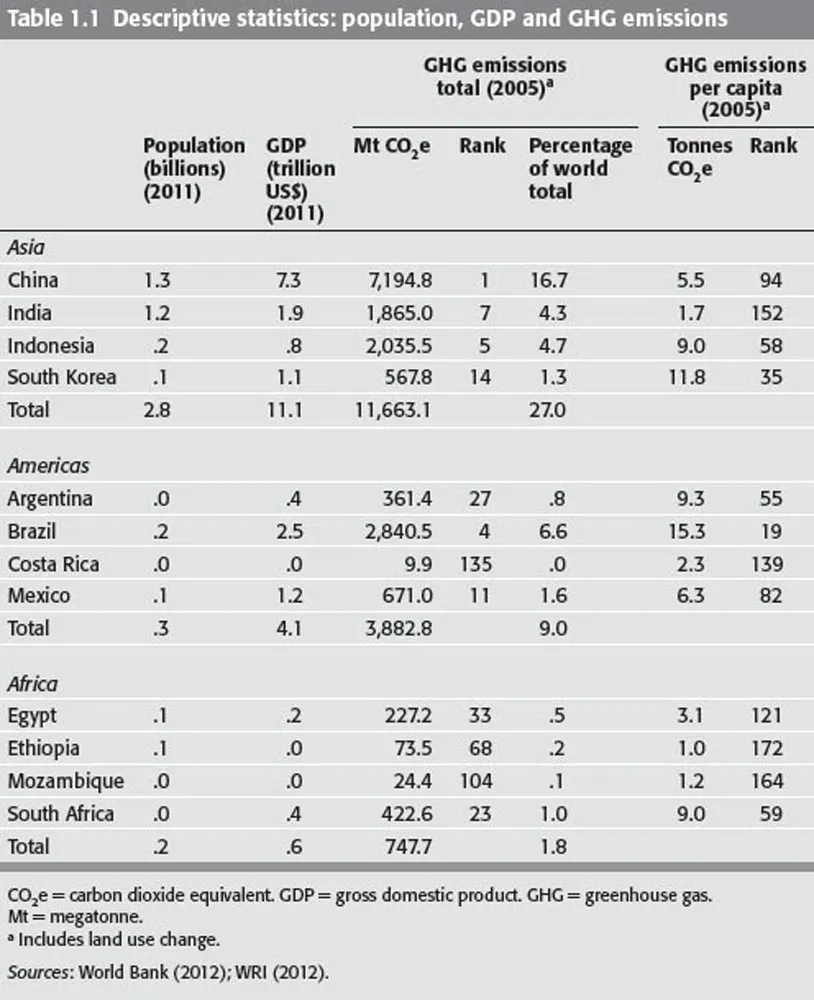

While the contexts within which developing and emerging economies are making their plans and commitments are different, as are their intentions and abilities to achieve them, we argue that there seems to be a new political dynamic underlying this remarkable set of developments that deserves careful scrutiny by both scholars and policymakers. Once considered perennial laggards, some developing countries are now widely regarded as climate policy leaders. Some commentators have even argued that a number of these countries are taking actions that are comparable to – or even more ambitious than – almost anything being done in the industrialized world. Our aim in this book is to explore such claims by closely examining the experiences of twelve important countries across three different regions: Asia, the Americas and Africa. In Asia we look at China, India, Indonesia and South Korea; in the Americas, Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica and Mexico; and in Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Mozambique and South Africa. Together, these countries account for around 50 per cent of the world’s population, about 25 per cent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and almost 40 per cent of the world’s annual emissions of GHGs at present (when land use change is taken into account) (see table 1.1).

Four of the countries analysed in this book – Brazil, China, India and Indonesia – are ‘major’ emitters, accounting for almost 85 per cent of all the emissions produced by the countries we consider. They are all among the top ten annual emitters of GHGs globally, and account for over 50 per cent of the developing world’s total emissions. These states are therefore intrinsically important from a normative or policy perspective, and have attracted a great deal of interest in scholarly and policymaking communities. Five of the countries – Argentina, Egypt, Mexico, South Africa and South Korea – are ‘middle range’ producers of GHGs. Their annual emissions are often comparable to those of many European states in absolute and, in some cases, per capita terms (South Korea, for instance). Although they are not individually decisive, the participation of a large number of such states in global mitigation efforts is essential, as they account for a significant share of emissions as a group. Together, the annual emissions produced by these five are similar to India’s or Brazil’s. Finally, we also consider several smaller ‘minor’ emitters – Costa Rica, Ethiopia and Mozambique – which are interesting precisely because they are not decisive, and yet (at least in the cases of Costa Rica and Ethiopia) have announced commitments to becoming ‘carbon neutral’ or ‘carbon free’ in the near future.

The cases we have chosen are not of course representative of the total ‘universe’ of developing countries. Indeed, several lacunae should be immediately apparent. We do not analyse countries from West and Central Asia, some of which may fall into the category of ‘middle range’ emitters, nor do we consider small island developing states, some of which have made commitments to carbon neutrality (the Maldives and Tuvalu, for example). Exploring the dynamics of climate governance in such states offers an opportunity for future research and comparative analysis, but they are not dealt with in this study. Our cases were chosen primarily because they have submitted NAMAs or made unilateral commitments of various kinds to taking action on climate change. Overall, only 30 per cent of all non-Annex I countries have submitted NAMAs to the UNFCCC secretariat. Of the twelve analysed in this book, only Mozambique and Egypt have not developed NAMAs, though their experiences are interesting in other highly suggestive ways, discussed further below. These cases therefore constitute a unique group, but one which is intended to be broadly representative of the subset of developing countries that claim to be taking a more ambitious approach to the climate. The aim of each chapter is to examine the international and domestic contexts within which these commitments have been made, the interests at stake, the actors involved and the strategies and policies that have been developed.

In the rest of this introductory chapter, we first discuss why it is increasingly essential to understand the way climate governance is evolving in the developing world. We argue that it is important, above all, because developing countries are having a much greater effect on the climate than in previous decades. However, there are major theoretical issues at stake as well, as current theories of climate politics are not optimistic about the potential for effective climate governance in developing states. Thus, the finding that developing countries are taking action on the issue seems fundamentally to overturn some widely held assumptions about climate and environmental politics in the developing world. Having explored these issues, we then provide a brief overview of the individual cases, highlighting some of the most salient or interesting features and findings that they bring to light. Finally, we conclude by discussing some broad themes that appear across a number of the cases, and which bear upon the theoretical and policy-oriented questions that motivate this book.

What is at Stake?

Understanding how and why some developing countries have become more ambitious with respect to climate change is important, first of all, from a policy or normative perspective. Some developing countries are now major contributors to climate change on a number of measures. Indeed, the annual contributions of some developing states to total annual greenhouse gas emissions are comparable to or even greater than those of states in the developed world. China’s share of total annual CO2 emissions rose from 11 per cent in 1990 to nearly 24 per cent by 2006, and it is now the world’s single largest emitter of GHGs. Individually, Brazil, India and Indonesia each now produce more GHGs each year than Japan or Germany, Asia’s second largest and Europe’s largest economy. South Korea produces more GHGs than France or Italy. Iran produces more GHG in absolute terms than all of Australia. Although many smaller developing countries are not yet major producers of GHGs, if we look at another measure – per capita emissions – it is clear that many are relatively large contributors on a per person basis. The list of top per capita emitters includes a great number of non-Annex I states, such as Belize, Guyana, Qatar and Malaysia. Among industrialized states, only Australia (the ninth largest per capita emitter in the world) makes the top ten.

Figure 1.1 Projected global emissions, 2010–50

Source: Based on data from the figure ‘GHG emissions: baseline, 2010–2050’ from OECD Environmental Outlook Baseline; output from IMAGE/ENV-Linkages.

CO2e = carbon dioxide equivalent.

In total, non-Annex I states currently account for just over half of all GHG emissions in absolute terms, with a few states like China, Brazil and India making up about half of that number in turn. Yet, as economies in the developing world grow, their contributions are only likely to get much larger if major changes do not take place today. As figure 1.1 shows, annual emissions from Annex I states are expected to be relatively stable between now and 2050. Emissions in the United States and Canada are rising and will continue to do so, while emissions in the European Union are expected to fall, though not nearly fast enough for the total level for all Annex I countries to decline. Annual emissions from non-Annex I states, on the other hand, are expected to grow by around 45 per cent. Emissions from Asia are likely to rise by about 53 per cent while those from Latin America and Africa will rise by about 26 per cent each, albeit from very different bases. Thus, developing states will naturally comprise a much larger share of total annual GHG emissions in a relatively short period of time, and their participation in mitigation efforts will be absolutely necessary if global levels of GHGs are to be stabilized at safe levels. In fact, emissions in the developing world are expected to grow so fast according to most ‘business-as-usual’ scenarios that, even if the industrialized world managed to reduce its emissions to zero by 2040, total global emissions will still be higher than they are today if no changes are made. At the very least, therefore, developing states will have to shift downward the trajectory of their emissions pathways, though many will need to make absolute reductions as well (for further discussion of required non-Annex I commitments see Elzen & Höhne 2008).

One of the best known and most often heard claims about climate change is that it is the historical emissions of industrialized countries that are largely responsible for triggering climate change. For this reason, the UNFCCC states that it is the now-developed world that ‘should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof’ (UN 1992, p. 4). H...

Table of contents

- Cover

- HalfTitle

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- 1. Editors’ Introduction: Climate Governance in the Developing World

- Part I Asia

- 2. A Green Revolution: China’s Governance of Energy and Climate Change

- 3. The Evolution of Climate Policy in India: Poverty and Global Ambition in Tension

- 4. The Dynamics of Climate Change Governance in Indonesia

- 5. Low Carbon Green Growth and Climate Change Governance in South Korea

- Part II Americas

- 6. Discounting the Future: The Politics of Climate Change in Argentina

- 7. Controlling the Amazon: Brazil’s Evolving Response to Climate Change

- 8. Making ‘Peace with Nature’: Costa Rica’s Campaign for Climate Neutrality

- 9. A Climate Leader? The Politics and Practice of Climate Governance in Mexico

- Part III Africa

- 10. Resources and Revenues: The Political Economy of Climate Initiatives in Egypt

- 11. Ethiopia’s Path to a Climate-Resilient Green Economy

- 12. Reducing Climate Change Vulnerability in Mozambique: From Policy to Practice

- 13. Reaching the Crossroads: The Development of Climate Governance in South Africa

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Climate Governance in the Developing World by David Held,Charles Roger,Eva-Maria Nag,David Held in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.