- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This new textbook opens up the policy-making process for students, uncovering how government decisions around health are really made. Starting from more traditional insights into how ministers and civil servants develop policy with limited knowledge and money, the book goes on to challenge the conception of policy as a rational process, revealing it to be something quite different.

Knee-jerk reactions to disasters, keeping voters satisfied, the powerful leverage of interest groups, and the skewing of debate through ideology and the media are each considered in turn. These processes render policy far from rational or at least require a much broader approach for considering policy 'logic', one that is open to different rationalities of values, norms and pragmatism. The book draws on historical and contemporary examples to highlight that though challenges to policy-makers may seem in some ways novel, in many senses key processes endure and indeed are rooted in historical contexts. Although the examples are drawn from UK health and social care, the book's theory-driven approach is applicable across national contexts Ð especially for countries where uncertainty, risk and resource pressures create significant dilemmas for policy-makers.

The book's multi-perspective, thematic approach will be especially relevant to students, as will the broad range of case study examples used. Making Health Policy will be essential reading for students of health policy, social policy, social work, and the sociology of medicine, health and illness.

Knee-jerk reactions to disasters, keeping voters satisfied, the powerful leverage of interest groups, and the skewing of debate through ideology and the media are each considered in turn. These processes render policy far from rational or at least require a much broader approach for considering policy 'logic', one that is open to different rationalities of values, norms and pragmatism. The book draws on historical and contemporary examples to highlight that though challenges to policy-makers may seem in some ways novel, in many senses key processes endure and indeed are rooted in historical contexts. Although the examples are drawn from UK health and social care, the book's theory-driven approach is applicable across national contexts Ð especially for countries where uncertainty, risk and resource pressures create significant dilemmas for policy-makers.

The book's multi-perspective, thematic approach will be especially relevant to students, as will the broad range of case study examples used. Making Health Policy will be essential reading for students of health policy, social policy, social work, and the sociology of medicine, health and illness.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making Health Policy by Andy Alaszewski,Patrick Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Rationality in Policy Making

2

Managing knowledge and expertise: attempting to create rational health policy

AIMS

To examine the importance of knowledge in rational policy making and to consider ways of dealing with the challenges for governments in accessing and using appropriate knowledge, and how they have responded to such challenges.

OBJECTIVES

• To consider the importance of the effective use of scientific knowledge and expertise in rational health policy making

• To identify the challenges in the UK, especially the knowledge gap that results from appointment of key policy makers – ministers – who do not have expertise in the domain of health

• To consider the ways in which policy issues are logically grouped together and the relative stability of those grouped around health

• To examine the impact which the search for better knowledge and expertise has had on the machinery of health policy making in the UK.

In chapter 1 we noted the ways in which contemporary governments seek to justify their actions and policies in terms of the rationality of their policies and the benefits which these policies create for citizens. In this chapter we develop this analysis by examining the importance of scientific knowledge in rational policy making and the knowledge deficit that results from the appointment in the UK of ministers who have political expertise but not necessarily any specialist knowledge of the policy area they are responsible for. We consider the ways this problem is overcome through the use of advisers, and the on-going search for improvements in access to expertise and knowledge.

2.1 Rationality in policy making: using appropriate knowledge

In the Enlightenment programme the rationality of government action is defined in terms of instrumentality, i.e. as the best means of achieving specified ends. Such instrumental rationality is grounded in scientific knowledge of the best ends or outcome and the most effective way of achieving the desired outcome. The American sociologist Talcott Parsons argued that policy is rational: ‘in so far as it pursues ends possible within the conditions of the situation, and by the means which, among those available to [the policy maker], are intrinsically best adapted to the ends for reasons understandable and verifiable by positive empirical science’ (Parsons 1949: 58).

Simon identified the processes underlying rational policy making in the following way:

the work that steers the course of society and its economic and governmental organisations – is largely work of making decisions and solving problems. It is work of choosing issues that require attention, setting goals, finding or designing suitable courses of action, and evaluating and choosing among alternative actions. The first three of these activities – fixing agendas, setting goals, and designing actions – are usually called problem solving; the last, evaluating and choosing, is usually called decision making. Nothing is more important for the well-being of society than that this work be performed effectively, that we address successfully the many problems requiring attention at the national level (the budget and trade deficits, AIDS, national security, the mitigation of earthquake damage). (Simon 1986: 1, italics added)

Simon argued that it is possible to consider the best way of approaching such problems and to identify systems that will maximise benefit, i.e. specify ‘the conditions of perfect utility-maximizing rationality in a world of certainty’ (1986: 1). His caveat that policy making can only be rational in a world of certainty acknowledges that in reality there is uncertainty, i.e. an absence of full knowledge, and that policy makers need to improve policy making by improving their access to knowledge.

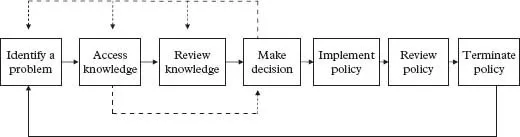

Simon argued that rationality involves a sequence of activity starting with the identification of a policy problem, and moving through the identification and evaluation of alternative ways of dealing with the problem to decision making and policy implementation. Jenkins (1978) represented rational policy making as a series of activities linked by feedback loops. The main loop leads from the termination of one policy to the start of the next as shown in figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 A diagrammatic representation of a rational policy-making system Adapted from Jenkins 1978:17

While both Simon and Jenkins indicate that rational policy making starts with either choosing issues or identifying a problem, there is actually little discussion of how such issues or problems are identified. The implication in rational planning is that ends are defined in the same way as the evaluation of means, i.e. through the accumulation of knowledge. However, as we will show in chapter 6 when we focus more closely on the ways in which issues, problems or the desired ends of policy making are determined, it becomes clear that knowledge is neither sufficient nor necessary.

In the Enlightenment programme, policy is only rational if there is full or at least adequate knowledge about the nature of social problems, the possible responses to such problems and the probable outcomes of these responses. Policy makers need to draw on the knowledge created by scientific investigation, but where this is inadequate they need to create additional knowledge, for example by funding the scientific investigation of practical problems. As we will discuss in chapters 5 and 9, policy makers are under pressure to respond quickly to new problems and often do not consider they have the time to commission and respond to new knowledge (Toynbee 2010). Creating new knowledge means resisting the Enlightenment imperative to take action. For example, in the case of HIV/AIDS in the early 1980s and vCJD in the early 1990s policy makers were criticised for inaction, even though they had commissioned scientific research that identified the nature of the new diseases (see box 2.1 for HIV/AIDS, and, for vCJD, box 5.1).

This emphasis on acquiring and using appropriate knowledge and expertise reflects a concern to use available resources in the most effective and rational manner and also to minimise irrational and arbitrary influences. The Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has advocated an evidence-based policy-making system that counteracts ‘short-term political pressures’ through the use of evidence.

Box 2.1 HIV/AIDS: using scientific knowledge to establish the nature of the problem

Historical context In the early 1980s a new disease was identified, initially on the West Coast of the USA and subsequently in major cities in Europe. It appeared to be associated mainly with men who have sex with other men and there was considerable media coverage with a strong moralising dimension.

Process The Conservative Government provided additional monies for the Medical Research Council to fund scientific investigation into the nature and causes of the new disease.

Outcome By 1985 the disease was identified as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and the consensus of scientific opinion was that it was caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) which spread through bodily fluids especially blood, via sexual activity, sharing of intravenous injection equipment and contaminated Factor VIII clotting agent. Such knowledge underpinned the development of various preventative measures.

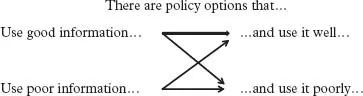

The key benefit of evidence-based policy making is better policy. The recent increase in interest in evidence-based policy making comes in response to a perception that Government needs to improve the quality of decision-making . . . Many critics argued in the past that policy decisions were too often driven by inertia or by short-term political pressures. There are many different definitions of the term ‘evidence based policy making’ but we use it here to refer to an approach to policy development and implementation which uses rigorous techniques to develop and maintain a robust evidence base from which to develop policy options. (DEFRA n.d.)

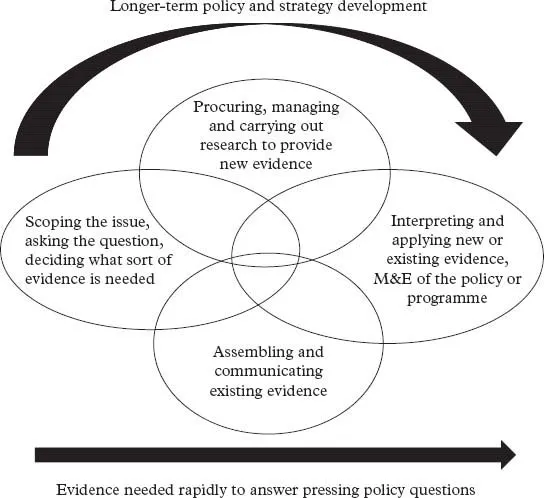

The main elements of this system are presented in figures 2.2 and 2.3.

In the rational model, policy makers should be objective experts who apply reason and knowledge to identify society’s problems and make decisions that create maximum social benefit. Thus, for advocates of rational policy making, the key to good policy making is appropriate knowledge that is effectively analysed. The Haldane Inquiry in 1918 into the operation of government emphasised the importance of ‘investigation and thought as a preliminary to action’ (Hennessy 1990: 297). However, as we will show in the next section, there is a major problem in policy making in the UK as the key group of policy makers, government ministers, are not appointed because of their expertise – or even interest – in a particular policy area.

Figure 2.2 DEFRA assessment of the use of information in policy Source: DEFRA

Figure 2.3 The use of evidence in policy making Source: DEFRA

2.2 A knowledge deficit: ministers and their policy expertise

Ministers are key policy makers and the public face of policy. They are responsible for publicly stating and explaining policy decisions. As we discuss in chapter 9, this involves explaining such policies to and through the media. Since the United Kingdom is a democracy, the public is represented by Members of Parliament, and therefore ministers have to present and explain their policies to Parliament. Hence the convention in the United Kingdom that ministers must be Members of the House of Commons or Lords: ‘The basic requirement of accountability is that ministers explain their actions and policies to Parliament, and inform Parliament of events or developments within their sphere of responsibility’ (Powell and Gay 2004: 7).

Since ministers are responsible for the formation and implementation of policies within specified areas, they should apologise for and rectify errors if these result from their policies. When the errors and their consequences are serious, they should resign. However, there is considerable dispute about what exactly constitutes an ‘error’, especially one so serious that it necessitates resignation. Indeed, despite the major health disasters which we examine in chapter 5, such as murders committed by Harold Shipman and Beverley Allitt, there have been lots of apologies but very few resignations. Of the 125 ministerial resignations in the twentieth century, only one was in the area of health: Edwina Currie (see Powell and Gay 2004: 35–7). In a radio programme in December 1988, Currie, a junior health minister in the Conservative Government, referred to widespread concerns about egg production, stating that most of this production was contaminated with salmonella, resulting in a slump in sales of eggs. She was forced to resign – probably to ensure government relations with egg producers could be restored (Powell and Gay 2004: 27).

The importance of ministers as the public face of policy creates a major paradox. Ministers, particularly in the UK government system, are usually successful politicians but they have little experience of policy making and limited knowledge of the substantive area for which they become responsible. As Dror noted: ‘The nature of political competition in democracies emphasises criteria that have little correlation with the qualities needed for some of the main tasks of rulers, especially policy-making’ (1987: 191). Prime Ministers, who appoint ministers in the UK, have a small pool of people to select from. In 2008 the Government was made up 118 ministers, of whom 25 were in the House of Lords and 93 in the House of Commons (Cabinet Office 2008). Most of the senior ministers (members of the Cabinet) were in the Commons (21 out of 23). Thus, when choosing senior ministers and most junior ministers, the Prime Minister is restricted to Members of Parliament who accept the government whip, i.e. between 325 and 425 Members of Parliament who belong to the party – or in the case of the 2010 election, coalition of parties – that won the preceding general election. However, the Prime Minister can extend his options by making appointments to the House of Lords. In 2007, when he became Prime Minister, Gordon Brown appointed non-party peers to his government of ‘all talents’ (Brown and Morris 2007), including Professor the Lord Darzi of Denham as a junior health minister, who is profiled in box 2.2.

The Prime Minister needs to ensure that his or her government team can effectively present and defend government policies and that it includes all key politicians within the party. Hence it is unlikely that many ministers, when appointed, will have particular knowledge of the policy area for which they are responsible. In many European countries, it is common practice for the minister responsible for health policy to have relevant expertise, i.e. be a doctor. In the United Kingdom none of the Secretaries of State since 1968 have been medically qualified. Virginia Bottomley, Secretary of State for Health from 1992 to 1995, however, did have professional training as a social worker and expertise in policy issues as a social scientist and former researcher for Child Poverty Action Group. There have been Ministers of State with medical qualifications, the most famous being Dr David Owen from 1974 to 1976.

The lack of both interest and expertise was evident in the case of Sir Norman Fowler. He came from a private-sector background and made it clear that he was interested in policy making relating to this sector. When the Conservatives were elected in 1979, the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, acknowledged this interest and gave him responsibility for Transport. In 1981 when she culled the ‘wets’ in her Cabinet she unexpectedly offered Fowler responsibility for health and social services. He publicly stated that he knew nothing about social policy but accepted the post. Despite his limited interest and expertise, he retained the post of Secretary of State for Social Services until after the 1987 election when he was offered the post of Secretary of State for Employment.

Health ministers generally have very limited specialist knowledge of health. In 2008 there were six health ministers in England (Department of Health 2008a). In box 2.2 we provide profiles for two of these ministers: Alan Johnson, with a typical political career and limited health background, and Lord Darzi who had an atypical background. Of the six ministers in 2008, only two of the junior ministers, Lord Darzi and Ann Keen, had experience of working in the NHS, but both these junior ministers were appointed for their commitment to the New Labour programme of health reforms.

The Coalition Government elected in 2010 showed some differences from the normal pattern of ministerial appointments. There were only five health ministers in England, and only one junio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 Rationality in Policy Making

- Part 2 The Limits of Rationality in Policy Making

- Part 3 Conclusion

- References

- Index