- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intelligence in an Insecure World

About this book

Over a decade on from the terrorist attacks of 9/11, intelligence continues to be of central importance to the contemporary world. Today there is a growing awareness of the importance of intelligence, and an increasing investment in it, as individuals, groups, organizations and states all seek timely and actionable information in order to increase their sense of security.

But what exactly is intelligence? Who seeks to develop it and how? What happens to intelligence once it is produced, and what dilemmas does this generate? How can liberal democracies seek to mitigate problems of intelligence, and what do we mean by "intelligence failure?"' In a fully revised and expanded new edition of their classic guide to the field, Peter Gill and Mark Phythian explore these and other questions. Together they set out a comprehensive framework for the study of intelligence, discussing how 'intelligence' can best be understood, how it is collected, analysed, disseminated and acted upon, how it raises ethical problems, and how and why it fails.

Drawing on a range of contemporary examples, Intelligence in an Insecure World is an authoritative and accessible guide to a rapidly expanding area of enquiry - one which everyone has an interest in understanding.

But what exactly is intelligence? Who seeks to develop it and how? What happens to intelligence once it is produced, and what dilemmas does this generate? How can liberal democracies seek to mitigate problems of intelligence, and what do we mean by "intelligence failure?"' In a fully revised and expanded new edition of their classic guide to the field, Peter Gill and Mark Phythian explore these and other questions. Together they set out a comprehensive framework for the study of intelligence, discussing how 'intelligence' can best be understood, how it is collected, analysed, disseminated and acted upon, how it raises ethical problems, and how and why it fails.

Drawing on a range of contemporary examples, Intelligence in an Insecure World is an authoritative and accessible guide to a rapidly expanding area of enquiry - one which everyone has an interest in understanding.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Edition

2Subtopic

International RelationsCHAPTER ONE

What Is Intelligence?

Introduction

This chapter poses a seemingly straightforward question: what is intelligence? However, once we attempt to define intelligence, it soon becomes apparent that, as a concept, it is as elusive as the daring fictional agents who have cemented it in the popular imagination – partly because any worthwhile definition needs to go beyond the idea that it is solely about ‘stealing secrets’1 to embrace the full range of activities in which intelligence agencies engage and the purposes underpinning these.

Our starting point should be to recognize that intelligence is a means to an end. This end is the security, including the prosperity, of the entity that provides for the collection and subsequent analysis of intelligence. In the contemporary international system, states are the principal customers of intelligence and the key organizers of collection and analysis agencies. However, a range of sub-state actors, political, commercial and criminal, also perceive a need to collect and analyse intelligence and guard against the theft of their own secrets. In the contemporary world, this need even extends to sports teams. For example, ahead of the November 2003 rugby union world cup final against hosts Australia, the England team swept their changing room and training base for electronic surveillance equipment, concerned that in 2001 espionage had allowed an Australian team to crack the codes employed by the British Lions, helping secure their dominance in line outs and go on to win the series.2 Allegations of spying or espionage have also been a feature of Formula 1 motor racing and yacht racing via allegations of attempts to steal yacht designs.3 In high-value team sports there is a clear incentive to uncover and understand the secrets that produce a competitive edge.

Indeed, once we define it in terms of security it becomes clear that intelligence is an inherently competitive pursuit. Security is relative, and therefore the purpose of intelligence is to bestow a relative security advantage. Moreover, as discussion of sports espionage suggests, security is a broad concept which goes beyond preventing military surprise or terrorist attack. In Britain, the Statement of Purpose and Values of the Security Service (MI5) talks of protecting ‘national security and economic well-being’.4 The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) defines one of its priority areas as countering activities by foreign governments that ‘may be detrimental to Canada’s scientific and technological developments; that may harm our country’s critical economic and information infrastructures or that may affect our military, commercial interests, and classified government information’.5 In other words, a key dimension of security is preserving relative economic advantage and, from there, advancing it through the collection of financial and commercial intelligence on competitors – whether foreign states or sub-state actors such as competitor companies.

Ideally, intelligence will enhance security by bestowing on the wise collector, perceptive analyst and skilled customer a predictive power on which basis policy can be formulated. However, intelligence is often fragmentary. As a process it has been compared to the construction of a jigsaw puzzle. It begins with few pieces in place and although more may be collected over time, allowing for a progressively fuller picture to be constructed gradually, the analyst can never be sure whether all of the necessary pieces have been collected or some come from an entirely different puzzle. Unlike a conventional jigsaw, intelligence has no box to provide a picture of what the complete puzzle should look like. This is a matter for analysts’ (and customers’) judgement.6 As a consequence, customers need to be aware of the limits of intelligence if it is to be most effective as a basis of policy. This was the clear message contained in gently admonitory passages in the UK Butler Report, which arose out of the apparent intelligence failure over the question of Iraq’s WMD, discussed more fully in chapter 7. The Butler Report warned that:

These limitations are best offset by ensuring that the ultimate users of intelligence, the decision-makers at all levels, properly understand its strengths and limitations and have the opportunity to acquire experience in handling it. It is not easy to do this while preserving the security of sensitive sources and methods. But unless intelligence is properly handled at this final stage, all preceding effort and expenditure is wasted.7

Similarly, the 2004 Flood Report into Australia’s intelligence agencies warned that while its customers would like intelligence to possess the characteristics of a science, and despite the benefit of decades of technological innovation, it stubbornly remains more of an art:

In so far as it seeks to forecast the future, assessment based on intelligence will seldom be precise or definitive. This is particularly so when it seeks to understand complex developments and trends in future years. Greater precision is sometimes possible in relation to intelligence’s warning function – highlighting the possibility of a specific event in the near term future … But even in this field, precision will be hard to achieve. Intelligence will rarely provide comprehensive coverage of a topic. More often it is fragmentary and incomplete.8

The Concept of the Intelligence Cycle: Help or Hindrance?

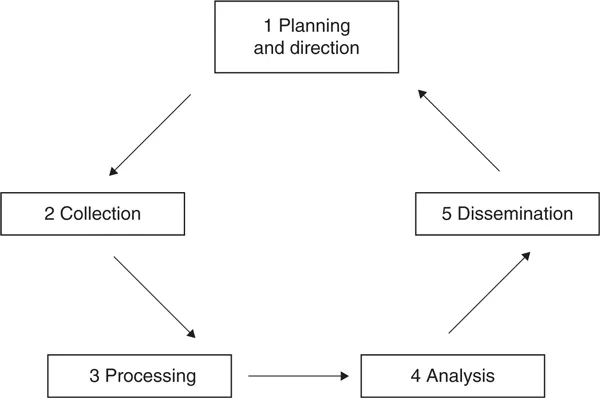

In defining ‘intelligence’, we need to recognize that it is an umbrella term – a fact that renders precise definition problematic – covering a chain or cycle of linked activities from the targeting and collection of data (only half-jokingly defined by former US Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan as ‘the plural of anecdote’9), through analysis to dissemination and the actions, some covert, which can result.10 The intelligence process has traditionally been explained by reference to the concept of the intelligence cycle, typically held to comprise five stages:

• planning and direction,

• collection,

• processing,

• all-source analysis and production, and

• dissemination.

For example, figure 1.1 shows how the CIA explains the intelligence process.

Intelligence collection – the subject of chapter 4 – involves accumulating the raw information that will be fed into the analytical process, either via open sources such as newspapers, books and official (government) publications or via secret human sources and whatever technical sources the intelligence agency has at its disposal. It is worth bearing in mind that these can vary widely from state to state and at sub-state levels. Not all intelligence agencies possess the technological capabilities or reach of western, Russian or Chinese state intelligence agencies. Processing can include technical issues such as transcribing and translating intercepted telephone conversations and verifying the reliability of information. Analysis is the process of determining what the information ‘means’. This is the crucial stage in the production

Source: http://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/facttell/intelligence_cycle.html

Figure 1.1 The intelligence cycle

of intelligence, for it is the analytical process (examined in more detail in chapter 5) that transforms the information, however acquired, into usable intelligence.

The CIA defines this stage of the intelligence process as involving:

the conversion of basic information into finished intelligence. It includes integrating, evaluating, and analyzing all available data – which is often fragmented and even contradictory – and preparing intelligence products. Analysts, who are subject-matter specialists, consider the information’s reliability, validity, and relevance. They integrate data into a coherent whole, put the evaluated information in context, and produce finished intelligence that includes assessments of events and judgments about the implications of the information.11

The language employed in the finished product is crucial. In a field which deals with estimates and probabilities, it is essential to convey accurately to the policymaker the degree of certainty underpinning judgements. It needs to be calibrated according to a commonly understood scale. Unfortunately, no such scale exists, a fact exposed by inquiries into intelligence on Iraq’s WMD. As Sherman Kent wrote, the language used should ‘set forth the community’s findings in such a way as to make clear to the reader what is certain knowledge and what is reasoned judgment, and within this large realm of judgment what varying degrees of certitude lie behind each key statement’.12

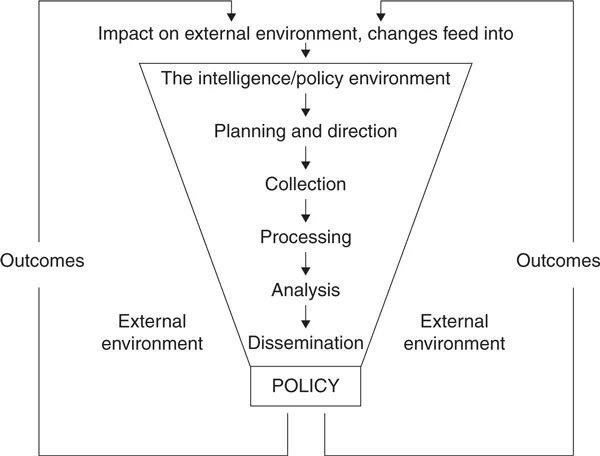

In recent years the utility of the concept of the intelligence cycle has been called into question. Like all models, it is a simplification of a more complex reality. While useful as a means of introducing the different stages of the intelligence process, the notion of a cycle fails to capture fully the fact that the end product of intelligence is an assessment designed for the customer that the customer then uses in formulating policy or operations. It feeds into and has the capacity to alter the very environment in which information was collected and analysis undertaken. The concept of a cycle cannot, in other words, capture the dynamic nature of intelligence’s impact on the external environment. An alternative way of viewing the intelligence process in order to capture this dynamic fully is to adopt the concept of a system that includes feedback, as in the ‘funnel of causality’ (figure 1.2).13 Moreover, the funnel shape indicates the point that not all information is necessarily translated via analysis into policy; much is filtered out.

Another problem with the concept of the intelligence cycle is that it invariably begins with direction from policymakers. The largest collectors of intelligence permanently cast their nets wide, sweeping up all information within their reach. The breadth of this sweep has implications for what we understand ‘targeting’ to mean. Notwithstanding this, targeted collection responds to international developments, but this response – the determination of the information to be targeted – is usually the business of intelligence managers, because it is they who are aware of the gaps in existing knowledge. As Arthur Hulnick has argued: ‘Filling the gaps is what drives the intelligence collection process, not guidance from policy makers.’14 Understanding intelligence in

Figure 1.2 The intelligence process

terms of uncertainty and risk calls this aspect of the intelligence cycle into question for similar reasons.15

The precise arrangements by which priorities are established for agencies vary; for example, in the UK the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC; see further in chapter 3) establishes the ‘requirements’ for MI6 and Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), but MI5 retains autonomy in determining its own priorities. After 9/11 it formally allocated some institutional resources to looking ahead for ‘emerging threats’ (see table 3.1 below), but this does not seem to have survived renewed emphasis on counterterrorism after 7/7, and Eliza Manningham-Buller, Director-General from 2002 to 2007, later admitted that the Service had not been very successful in this task.16

The idea that intelligence agencies await and then respond to policymaker direction is one that is most relevant to liberal democratic contexts, and is an extension of the principles governing civil–military relations in established democracies. Outside of this context, intelligence agencies may enjoy greater degrees of autonomy in determining targets and direction. For example, in the former GDR, the Stasi clearly enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy in determining targets, to the extent that it has been discussed in terms of representing a ‘state within a state’.17 In its early years a foreign intelligence agency – the KGB – played a key role in setting its agenda. Even in formal democracies, intelligence agencies can operate with a significant degree of autonomy – for example, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) in contemporary Pakistan, and the Servicio de Inteligencia Nacional (SIN) in Peru under spy chief Vladimiro Montesinos.18

Beyond issues around targeting and collection, the concept of the intelligence cycle suggests that the collection and analytical functions are sequential, that the latter can only begin once the former is complete. This is not the case, and in practice collection and analysis occur broadly concurrently. The cycle concept also rests on the implicit assumption that policymakers await objective analysis before deciding on a course of action. This assumption has been criticized by several commentators in the wake of the Iraqi WMD case. For example, Stephen Marrin has argued for an alternative understanding of the relationship between intelligence analysis and decision-making where, ‘rather than start with the intelligence analyst, it starts with the concepts and values being pursued by the decision-maker which determine the meaning and the relevance of the intelligence analysis that is provided to them’.19

Hence, it is wrong to think, as the intelligence cycle seems to imply, that policymakers wait for the analytical product before embarking on an action. They may well seek intelligence analysis that matches and supports an existing policy or policy preference. If they don’t get it they may ask for further analysis – or even question analysts personally, as Vice President Dick Cheney did in rel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- Preface to the Second Edition

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Development of Intelligence Studies

- 1 What Is Intelligence?

- 2 How Do We Understand Intelligence?

- 3 Who Does Intelligence?

- 4 How Do They Gather Information?

- 5 How Is Information Turned into Intelligence?

- 6 What Do They Do with Intelligence?

- 7 Why Does Intelligence Fail?

- 8 Can Intelligence Be Democratic?

- 9 Intelligence for a More Secure World?

- Notes

- Selected Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Intelligence in an Insecure World by Peter Gill,Mark Phythian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.