Social movements are key forces of social change in the modern world. Although not all social change emanates from them – technological innovation, climate change, natural disasters, and wars also are causes – social movements are unique because they are guided purposively and strategically by the people who join them. Another key characteristic is that they mobilize and do their business mostly outside established political and institutional channels. This makes questions of their origin and growth especially compelling for the social scientist. Some social movements represent efforts by citizens to collectively create a more just and equitable world. Other movements are motivated by compelling grievances that push their adherents out of their ordinary daily routines. Social movements are typically resisted by forces that favor the status quo, which imparts a fundamental contentiousness to movement actions. But the defining characteristic of all movements, big and small, is that they move history along, sometimes in significant ways. Knowing what they are and how social scientists study them are important tasks if we are to understand contemporary society and where it is headed.

In 2011, Time magazine selected “the protester” as its person of the year. This was partly because movements in opposition to repressive regimes exploded that year in North Africa and the Middle East. In both Egypt and Tunisia, the Mubarak and the Ben-Ali regimes were brought down by unexpected mass movements of political opposition. In Syria, a similar opposition movement took a different course. It spiraled into a civil war with casualties over 100,000 and a flow of refugees approaching 1.5 million. Many social movements voice wide-ranging demands for political change – in these cases, demands for the overthrow of the old regime and the ushering in of a new, more democratic system.

Also that year, another wave of protests occurred in several Western countries in the form of the Occupy movement in the US, the 15-M (for May 15) movement in Spain, and large anti-austerity protests in the UK, Ireland, and Greece. These protests shared common themes that grew out of the global economic collapse, the complicity of political elites, and their failures regarding economic policy. These movements were less successful in achieving their immediate goals, but they did create networks of activists, linked by the new social media, which serve as the basis for continued social-change activism. They also elaborated new tactics of site occupations of central squares and plazas and radical participatory democracy that will have strategic effects in other future movements.

In addition, a huge but less bounded cultural shift is occurring in North America and Europe, again precipitated by a social movement. I have in mind the gay rights movement, a network of organizations and groups that are less in the headlines than the above two examples, but which have worked for decades to fight discrimination, promote equality, and change attitudes about homosexuality and marriage. In the US just twenty years earlier, the Defense of Marriage Act, which banned gay marriage at the federal level, was passed by the Clinton administration with little congressional opposition. Today, a majority of US citizens are not opposed to gay marriage. Ex-President Clinton (and his wife – perhaps a future president) both publicly affirm that the Defense of Marriage Act was a mistake. While gay marriage still remains a contentious issue, it is fair to say that this shift in public opinion would not have occurred without the various campaigns of the gay rights movement.

These are different kinds of movements. Those that occurred as part of the Arab Spring were obviously political, and protesters risked a great deal taking action against repressive states. In democratic polities such as Spain and the United States, social movements are quite common, and at any given time the analyst finds numerous movements mobilizing on a wide variety of issues and claims. They are an important part of the political landscape whereby diverse groups and organizations promote their interests, make demands, and articulate their visions of change. The gay rights movement has political dimensions as it fights for marriage equality, which means that it must fight against legislation such as the Defense of Marriage Act and against the anti-gay marriage Proposition 8 in my home state of California. But it also has a cultural dimension in changing ideas about marriage, sexuality, and gendered performances that may be less apparent but no less important in the scope of social change. Numerous groups and organizations in the GLBT (for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender) movement have contributed to this effort over the years in different ways.

It is a large undertaking to navigate the complexity of these political, cultural, and organizational elements in a research project, and the analyst must make decisions about where to begin, which groups to include and which not to, what to focus on and what to place aside. Moreover, every social researcher knows how essential it is to define one's terms precisely. A good starting place for this book is to clarify those decisions about how we come to know about a social movement – its boundaries regarding which groups, ideas, and actions are included and which ones are not.

The Study of Social Movements

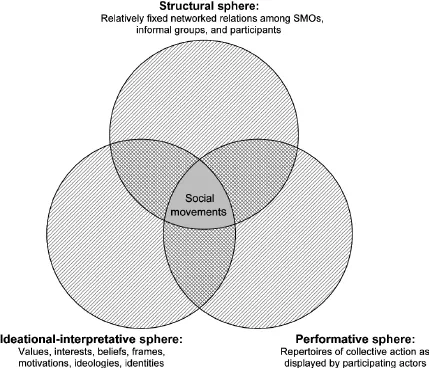

I approach the study of social movements guided by Charles Tilly's observation (1978: 8–9) that the field's basic analytical dimensions are: (1) the groups and organizations that make up a collective action; (2) the events that are part of the action repertoire; and (3) the ideas that unify the groups and guide their protests. He stressed that, when we study social movements, we tend to focus on just one of this trinity, which, in turn, pulls us into related areas of the other two spheres. For example, if we are interested in studying a protest event – say, a huge antiwar protest in a large city – we are invariably drawn to the groups that organized it and then their ideas, which motivated their actions. Much has changed in the field of social movement research since Tilly offered these ideas, and they can be fine-tuned to better reflect how the field has advanced, while still maintaining the insight that a focus on one draws the analyst to the relevance of the others.

First, a large body of research has emerged to show that movement groups and organizations do not stand alone but rather are linked in network structures through overlapping memberships, interrelations among members, and contacts among leaders (Diani 1992; Diani and McAdam 2003; della Porta and Diani 2006). Taking into account the network structure of a movement that ties together various organizations of different size and formality, it is more accurate to refer to the broader structural sphere of a movement. It is a label that captures the relatively fixed networked relations among groups, organizations and individual participants that characterize social movements large and small. The structural sphere is a crucial focus because it is through interlinkages among organizations that resources are brought to bear for mobilization – getting people into the streets and applying pressure on politicians. These ties are also the skeletal structure of a movement's unity and continuity. Groups can dissolve and organizations can be torn by schisms, but the general movement is characterized by temporal persistence beyond the fate of just one group.

Second, the ideas that fuel a movement, guide it, and give it cohesion include the time-tested and widely studied notions of ideologies, goals, values, and interests. In recent years, however, researchers have probed the concept of collective identity as a key ideational element that binds together the individuals and groups within a movement. Also, an important theoretical insight that has been widely applied in movement research is the concept of collective action frames. These are cognitive schemata that guide interpretation of events for movement participants, bystander publics, and political elites, and are distinct from a systematic ideology or vaguely defined cultural values and norms. Research has emphasized that both collective identity and interpretative frames are ongoing collective elaborations anchored in situations of interaction. This is a finding that moves research on these ideational dimensions from books, ideological tracts, and manifestos where movement goals and demands are expressed, to spoken interactions among participants. Thus I will use the term ideational–interpretative sphere of a social movement to capture how the analytical scope of a movement's ideas have been broadened in recent years.

Third, I extend Tilly's focus on the events to include all the elements in a movement's repertoire, how they are performed, and how they are reacted to. Tilly had been instrumental in developing a performative approach to social movements based on his concept of the modern social movement repertoire (1995, 2005, 2008). An emphasis on the performances of a movement rather than its protest events also follows cultural sociology's basic insight of social action as theatre. I emphasize the performance metaphor because, just as in other forms of social behavior, typical movement performances – street protests, demonstrations, strikes, marches, and so on – are strongly symbolic in the sense that they are making statements beyond just the content of their songs, chants, placards, and speeches. Also, they are performances because they always have an audience: those who witness the performances, interpret what they see, act upon their interpretations, and whose presence influences how the performance unfolds. Viewing a social movement protest as a performance puts it in its full context of the actors and the various audiences, and broadens the way we study social movements by situating them in dynamic relationships.

Figure 1.1 graphically represents a general model of how social scientists approach the study of social movements. The circles represent the three analytical spheres broadly: social structure, cultural ideations/interpretations, and the social performances of daily life. The core of the figure depicts the convergence of those elements characteristic of social movements. Putting it simply, the core concentrates (1) those interlinked groups and organizations that (2) carry and expound ideational–interpretative elements, such as identities, ideologies, and frames, that are (3) reflected and manifested in collective performances that we recognize as part of the modern social movement repertoire. The core region is where the analyst of social movements concentrates attention. Although one's interest originally may be focused on just one of the three spheres – a particular group's ideology, for example – the researcher is invariably drawn to other groups (via network ties) which share similar ideas, and how they translate their ideas to action. Implied is that there is an iterative and reinforcing relationship among the three. The figure also portrays three crosshatched areas that bud out from its core where only two spheres intersect. These areas capture how related groups, ideas, and actions that are not strictly part of the movement still may be interesting to the researcher because they occupy a middle ground that is less removed from ordinary, instutionalized social relations but at the same time supportive of social change. For example, a variety of groups – NGOs (nongovernmental organizations), advocacy organizations, and interest groups, all of which I will discuss shortly – would fall into this category and be located in the upper left of the three secondary areas.

Each of the larger spheres represents a fundamental dimension of social life with a wide distribution of different forms and foci, but the social movement analyst is interested in those that congeal towards center by virtue of how they challenge the status quo through extraordinary, noninstitutional actions. Let us take a closer look at the elements that concentrate at the core and how they give definition to what a social movement is.

The Structure of Social Movements

In the study of social movements, there are two basic ways of thinking about the structural sphere – that is, the relatively fixed and enduring relations among the social actors. First, social movements are composed of groups and organizations, large and small, contentious and tamed, that integrate individual members in varying degrees of participation and mobilize them to action. It is fair to say that these are basic units of movement structure, but – as I mentioned – there are also related groups that are relevant: advocacy groups, interest groups, and NGOs, and we need to differentiate among them as foci of study. Second, social movements are network structures. Given the ideological, tactical, and organizational complexity of social movements, a network organization interconnects this complexity, binding the components together, and imparting an overall cohesion. Just as some movement participants have multiple memberships, some organizations draw more members and have more central positions in the interconnected movement network.

Social movement organizations

A common error among beginning students is to mistake the organizations of a movement for the movement itself. In the case of the environmental movement, Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, or the Earth Liberation Front are social movement organizations, or simply SMOs. These are groups varying in their size, complexity, and formal structure that are organized by citizens to pursue their claims when politicians are unresponsive or when certain issues seem especially compelling. Sometimes SMOs are highly formalized and grow quite large, commanding vast resources, like Greenpeace or Nature Conservancy. But studying just the large SMOs would miss the breadth and complexity of the environmental movement. In addition to the large and significant SMO players, social movements also include small groups, some quite informal, that may be dedicated to somewhat different goals, but are, overall, guided by an environmentalist ethos. For example, groups of friends and acquaintances might create gardens in urban spaces, or encourage the use of bicycles instead of gas-guzzling cars and trucks. Social movements, in general, are complicated aggregations of diverse groups and individuals. The structural and organizational bases of social movements, taken as a whole, are usually diverse and complex, and always interrelated in a network of connections among different SMOs, informal groups, bystanders not yet fully committed to the movement, and individuals who may be favorably disposed to the movement but have not yet acted.

The centrality of SMOs in the study of social movements was first emphasized by John McCarthy and Mayer Zald (1973, 1977). They observed that a trend in modern movements was that SMOs were becoming larger, more formalized, and professionalized. They used the term professional social movement organization to refer to the increasing complexity of SMOs, often meaning full-time, salaried staffs. It should not be surprising, then, that some of the major figures in the field of study are also specialists in the analysis of complex organizations. The trend to professionalization contrasts with grassroots organizations that may arise more spontaneously and informally from an aggrieved population. Large change-oriented organizations may increase efficiency in planning and fundraising, thereby bringing in greater resources to be put at the disposal of movement goals, but they also have a downside in limiting member input and democratic decision making. Also, Piven and Cloward's classic study (1977) showed that large organizations were less likely to wage disruptive campaigns, which are the most effective tactics for resource-poor groups. Although professional SMOs tend to tame a movement's tactical repertoire, the overall trend is that they wield more and more influence in social movements, which means they are in positions to draw even more resources and influence, and grow and professionalize even more. This is a process that tends to marginalize smaller groups that comprise the movement.

Among the largest SMOs, marketing has become a big part of the professionalization trend. I regularly get glossy direct-mail solicitations from the Sierra Club, Amnesty International, Nature Conservancy, and other mega-SMOs. These mailings are costly to produce and require the purchase of mailing lists from other organizations, which is how I got on their lists – thanks to my wife who joined the Sierra Club a few years ago. Fundraising creates its own internal dynamic because of the high costs of direct mail and canvassing campaigns. They require a staff to design and direct them, which is a diversion of staff from the change-oriented goals of the movement. These large SMOs are more bureaucratically organized in that staff members have clear areas of authority and responsibility, of which direct-mail marketing is one.

Another trend is that the largest ones are becoming transnational in scope. These are sometimes huge organizations, such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth International. Transnational SMOs (TSMOs) will vary in their degree of centralization and coordination. Friends of the Earth is a decentralized organization, but other professionalized SMOs are more bureaucratic and hierarchical, such as Greenpeace, Worldwide Fund for Wildlife, Oxfam, or Amnesty International. These SMOs have main offices in Washington DC or London, and branches in other cities of the world. The paid staffs are professionals who must be educated, socially and linguistically skilled, and technically conversant in their areas of activism. Lahusen (2005) has traced the “cocktail circuit” of staff members of transnational environmental and human rights groups in Brussels and Geneva as they seek to influence the policymakers there.

The line separating large SMOs from interest groups that pursue more institutional approaches to political influence is often blurred. Interest groups are key sources of political influence in contemporary Western democracies. They are close cousins to SMOs because they apply pressure to politicians and exist on the fringes of established party politics, but are not so far removed from established activities that they would be called extrainstitutional in the same way that SMOs are. Interest groups are everywhere in modern democracies (Knoke 1986; Clemens 1997). Labor unions, ethnic-cultural groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Mexican-American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and industry groups like the National Association of Manufacturers, US Chamber of Commerce, and National Mining Association are just a few examples of large, formal, and complex organizations that represent the interests of economic and social groups. In the never-ending debate about guns and assault weapons in the US, the National Rifle Association is a...