- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

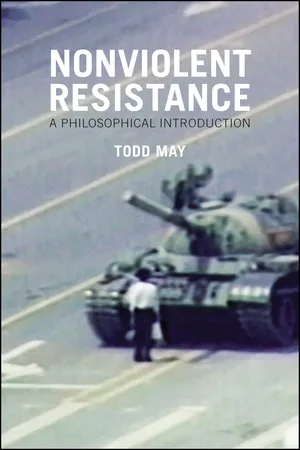

We see nonviolent resistance all over today's world, from Egypt's Tahrir Square to New York Occupy. Although we think of the last century as one marked by wars and violent conflict, in fact it was just as much a century of nonviolence as the achievements of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. and peaceful protests like the one that removed Ferdinand Marcos from the Philippines clearly demonstrate. But what is nonviolence? What makes a campaign a nonviolent one, and how does it work? What values does it incorporate?

In this unique study, Todd May, a philosopher who has himself participated in campaigns of nonviolent resistance, offers the first extended philosophical reflection on the particular and compelling political phenomenon of nonviolence. Drawing on both historical and contemporary examples, he examines the concept and objectives of nonviolence, and considers the different dynamics of nonviolence, from moral jiu-jitsu to nonviolent coercion. May goes on to explore the values that infuse nonviolent activity, especially the respect for dignity and the presupposition of equality, before taking a close-up look at the role of nonviolence in today's world.

Students of politics, peace studies, and philosophy, political activists, and those interested in the shape of current politics will find this book an invaluable source for understanding one of the most prevalent, but least reflected upon, political approaches of our world.

In this unique study, Todd May, a philosopher who has himself participated in campaigns of nonviolent resistance, offers the first extended philosophical reflection on the particular and compelling political phenomenon of nonviolence. Drawing on both historical and contemporary examples, he examines the concept and objectives of nonviolence, and considers the different dynamics of nonviolence, from moral jiu-jitsu to nonviolent coercion. May goes on to explore the values that infuse nonviolent activity, especially the respect for dignity and the presupposition of equality, before taking a close-up look at the role of nonviolence in today's world.

Students of politics, peace studies, and philosophy, political activists, and those interested in the shape of current politics will find this book an invaluable source for understanding one of the most prevalent, but least reflected upon, political approaches of our world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nonviolent Resistance by Todd May in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Vignettes of Nonviolence

In the capital, Tallinn, of the small country of Estonia, there is a large band shell. It can accommodate tens of thousands of people. The band shell can be seen from the top of the castle in Tallinn's Old Town, a complex that was spared the ravages of much of the destruction of World War II. Nestled in the hills outside the center of Tallinn, it is important for Estonians, since singing is part of their culture. Even during the Soviet occupation from 1945 to 1991, Estonians gathered every five years for a festival of song that drew large parts of the country's million-plus population. In fact, the band shell itself was constructed in 1960, during the height of the Soviet occupation. However, on the night of June 11, 1988, the role of song in Estonian life became much more than an expression of Estonian culture. It emerged instead as one of the primary weapons against the Soviet occupation itself.1

Earlier that evening, a concert had taken place in the Town Hall Square as part of Tallin's annual “Old Town Days” festival. Since daylight lasts late into the night during the short Estonian summer, those who attended the concert were not ready to call it quits after the music ended. Instead, thousands of them walked the several miles to the grounds of the band shell and began to sing. This in itself would be unremarkable. However, the next night the crowds grew to nearly 100,000 – almost ten per cent of Estonia's population. Moreover, several people – punk rock musicians – displayed the blue, black, and white Estonian national flag, which was banned under the Soviets. And, as one author describes it, “a man on a motorcycle, rock drummer Paap Kõlar, whipped around the perimeter of the amphitheater, moving like an apparition, as the Estonian colors that he carried fluttered above him. The crowd roared. For some young people, this was the first time they had seen their old national flag in public.”2

For six successive night Estonians gathered at the band shell to sing. Hundreds of thousands of them showed up every night to what was later to be called the “Singing Revolution.” Among the most important of their songs was one, based on a nineteenth-century poem and put to music by the composer Gustav Ernesaks, whose English translation is “Land of My Fathers, Land that I Love.” It was first performed at the song festival of 1947, its nationalist lyrics somehow escaping the Soviet censors. This is a bit puzzling, since the song laments, “Envy makes strangers slander you / You are still alive in my heart.” Over the years, it became the unofficial national anthem of Estonia. Although the Soviets tolerated it, they sought to change the lyrics to be more in accordance with the official “proletarian” orientation of the occupation. However, its lyrics and its significance remained for the Estonian people. Once, in 1969, during the centennial anniversary of the first singing festival in the university town of Tartu, the Soviet authorities decided to ban the song. However, after demanding that it be played, the concert attendees sang it themselves, over and over. Played at every song festival, “Land of My Fathers, Land that I Love” became the centerpiece of Estonian national expression.

The protests in the summer of 1988 did not wane with the dimming of the “White Nights” of summer. On September 10, organized by the resistance group the Popular Front, a singing protest drew 300,000 people, nearly a third of the country's entire population. By this time, the protest movement was in full sway. Speakers at the event railed against the Soviet occupation and asserted the national history of Estonia. At a time when Mikhail Gorbachev was allowing for glasnost – openness – the Estonian people were recovering their history and their country through their voices.

In the summer of 1989, one of the most remarkable protests in the history of the Soviet occupation occurred. On August 23, across the three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, a human chain of two million hand-holders gathered across 450 miles to protest against their collective occupation. The chain was timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the secret agreement between Hitler and Stalin that divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, giving the Baltic States and Finland to the Soviet Union. (The Pact itself was, of course, violated by Hitler when he invaded the Soviet Union.)

In Estonia, resistance to Soviet rule continued. Early in 1990, an alternative Estonian government was created, one that reflected a variety of different parties that had been organizing against the occupation. This alternative government began working on issues of statehood and citizenship in an envisioned independent Estonian polity, in competition with the daily administration emanating from Moscow.

However, as this unfolded, there was resistance not only from the Soviets but from within Estonia itself. Over the course of the occupation, the Soviet Union had adopted a policy of moving ethnic Russians into Estonia, and by the late 1980s they constituted a large percent of the Estonian population, and perhaps half of the population of the capital city of Tallinn. These Russians, far from looking forward to Estonian independence, saw it as a threat. The reason for this – and it is a source of continuing tension in Estonia – is that the Estonian movement did not so much want to declare independence as to restore it. This means that legal citizenship would only be available to legal descendants of the Estonians who were citizens before the Soviet occupation, effectively excluding the ethnic Russians who were currently living there.

In their turn, then, ethnic Russians began to create their own organizations to counter those developed by ethnic Estonians. In May 1990 the Supreme Council of the alternative Estonian government, in a move that inverted that of the Soviets, declared the hammer-and-sickle flag illegal. This move was publicly criticized by Gorbachev, which in turn prompted the Russian organization, Interfront, to protest in front of the Estonian parliament. The demonstration turned aggressive, with the protestors storming the gates of the building and re-planting the hammer-and-sickle. In response, the head of the parliament, Edgar Savisaar, got on the radio and announced the siege to the wider Estonian population. Thousands of Estonians soon turned up at the site, surrounding the Russians, who were unable to enter the parliament building and were now trapped in the courtyard of the complex.

At this point, it seemed impossible that violence could be avoided. The Interfront protestors had sought to overthrow the Estonian alternative government and replace it with the hated symbols – and reality – of Soviet rule. And they were now caught without any avenue of escape in the courtyard of the building they had sought, in an echo of Soviet rule, to occupy. However, at this moment a remarkable thing happened. Rather than attacking Interfront, the Estonians cleared a path to let them exit peacefully. As they moved through the human corridor that had been cleared for them, although the Estonian crowd shouted at them, none of the Interfront members were touched.

This, of course, was not the end of Soviet rule. The crowning moment came in August, 1991. At that moment in Russia, Soviet hard-liners had temporarily taken control of the government and removed Gorbachev as head of state. On August 20, the Estonian parliament declared independence. This declaration was rejected by the Soviets, who then moved tanks toward Tallinn. In particular, it sought to take over the television tower in order to coordinate its re-occupation and deliver instructions to the population. Realizing this, hundreds of Estonians rushed to surround the tower. Inside were two Estonian police officers. As the Soviet troops threatened to break into the tower, one of the policemen, Jüri Joost, threatened to release Freon from the fire extinguisher system. This would have killed everyone inside the tower, not only the troops but the policemen as well. Remarkably, while the Soviet troops were deciding how to respond to the threat, the coup in Moscow collapsed and the Soviet troops withdrew. Soon after, the new – or, more accurately, renewed – Estonian state was admitted to the United Nations.

The independence movement that finally liberated Estonia from Soviet rule was achieved without violence, even though there were moments that could have tipped the scales toward violent resistance. There were many reasons for this, having to do with the historical character of the Estonian people – for example, the importance of song in their repertoire of protest – to the specific dynamics of the situation as it unfolded in Estonia and the Soviet Union generally. It was also due to the patient organizing of several organizations that were developed in the 1987–8 period. Among those organizations were the Popular Front and the Estonian National Independence Party (which led one of the first open protests against the Soviet occupation in 1987), but also, and as important, the Estonian Heritage Society. Among the most important tasks for the Estonian people was a recognition of their own history, one that had been silenced throughout the Soviet occupation. This was particularly important for Estonia, since its history is one of occupation by foreign countries. Before the Russians there were the Germans, and before them the Swedes. In fact, until 1991 Estonia was an independent country only between the two World Wars. As significant as political resistance was to its liberation was the task of forming a sense of Estonia as a polity in its own right. The Heritage Society thus became a central player in the Estonian independence movement.

These organizations were often at work behind the scenes in the Singing Revolution and in interaction with the spontaneous events that were unfolding. It would be a mistake to assume too romantically that it was simply the singing that gained Estonian independence. In fact, an Estonian friend of mine, looking back on the events of that period, commented that, “it was just people singing, but suddenly, it was no longer just singing, if you see what I mean.”3

In addition to the organizations and mass protests that were formed during the period leading to independence, there were events of resistance preceding those of the 1987–91 period. We have already seen that, throughout the history of the Soviet occupation, the song “Land of My Fathers, Land that I Love” was a touchstone of resistance, and that the refusal of the Soviet censors to allow it to be sung in 1969 elicited mass resistance among those attending that year's festival. In late 1986 and early 1987, Estonian scientists and students demonstrated against phosphate mining off the shores of Estonia in what became known as the “phosphate war.” During the history of the occupation, the Soviets had engaged in exploiting Estonia's resources in environmentally degrading ways. Phosphate mining is a particularly egregious form of such degradation, allowing phosphates to seep into the ground water. It also served to bring in thousands of ethnic Russians as mine workers. The resistance to such mining, before the outbreak of the central events of independence, was successful in forcing the Soviets to cut back on plans to increase the mining of phosphates.

In fact, resistance to the occupation can be traced back to the beginning of the occupation itself. Guerilla fighters, who became known as the Forest Brothers because they would camp in Estonia's many forests, fought against the Soviet invasion of Estonia as they had fought against the Germans in World War II. Eventually, they were decimated, although one of them, August Sabe, survived until 1978 when he was betrayed by a Soviet agent. When he was discovered, he leapt into a river and killed himself.

The more recent history of Estonian resistance, however, those series of events that led to independence, were not the product of violent resistance. Grounded in patient organizing and song, they appealed to the national traditions of Estonia in order to garner the sustained support of the Estonian people – at one moment nearly a third of them – in order to keep alive the history and desires that the Soviets sought to suppress. Further, the use of those traditions was successful not only in re-creating the Estonian nation but also in preventing the kind of violence that would have offered excuses at particular junctures for further Soviet incursion. Finally, and most importantly, by staying within the boundaries of nonviolent activity, the Estonian people crafted a project of national liberation that expressed a dignity that can stand as a benchmark for its further development as a nation.

*

The beginning of the end of the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos can be given a specific date: August 21, 1983.4 On that day, opposition leader Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino stepped off the plane in which he had returned to Manila after three years in exile and was promptly shot dead.

Aquino, the most prominent figure in Filipino resistance to Marcos, espoused nonviolent resistance to the Marcos regime. He had not always done so. After Marcos' declaration of martial law in September 1972, Aquino was arrested...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1: Vignettes of Nonviolence

- 2: What is Nonviolence?

- 3: Dynamics of Nonviolence

- 4: The Values of Nonviolence: Dignity

- 5: The Values of Nonviolence: Equality

- 6: Nonviolence in Today's World

- Index

- End User License Agreement