- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The contemporary debate on economic policy is dominated by the issue of 'which model of capitalism works best'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Models of Capitalism by David Coates in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Capitalist Models and Economic Growth

Amid the optimism of a new century, the legacies of the past still lie like a nightmare on the brain of the living. Communism may have fallen (in Europe at least) but in the policy-making circles of the advanced capitalist world three quite enormous issues of economic policy remain to be resolved. In a capitalist economy, is the achievement of economic growth best left to the market, or should its orchestration be a central task of government? Do old ways of governing capitalist economies need now to be replaced by new ones? And should we be in pursuit of the one ‘right way’ of ordering economic and social life in the pursuit of economic growth, or do we still face a range of viable capitalist models?

These questions have all been around for a very long time, but they have gathered new urgency and force of late, as the pattern of economic performance among advanced capitalist economies has altered sharply. In the 1980s, in both the US and the UK, the policy debate was dominated by questions of economic decline, power was held by advocates of market-based capitalism, and the majority of their critics were pressing strongly for a managed economy of the seemingly more successful German or Japanese variety. By the late 1990s, in contrast, it was the German and Japanese economies that were widely perceived to be in difficulties, governmental power in both Washington and London had been captured by centre-left parties, and it was the advocates of unregulated capitalism who now offered sceptical opposition to the new ‘third way’ in politics. Suddenly, in the context of increasing globalization, old certainties have been replaced by new doubts; and the search is on again for solutions to problems of economic growth which, only a decade ago, appeared to have clear, definite, but varied solutions. In the face of such uncertainties, students of contemporary politics need rapidly to familiarize themselves with things hitherto of concern only to academic specialists: the causes of the various postwar economic ‘miracles’, the meaning and significance of globalization, the virtues and vices of flexible labour markets, the difference between first, second and third ‘ways’ in economic management, the nature of different capitalist models, and so on. The purpose of this volume is to facilitate that process of rapid learning.

The pattern of postwar economic growth

Economic growth is not the easiest thing to measure. On the contrary, the empirical and conceptual complexities of economic measurement are so contentious (and the implications of different modes of measurement for the results generated so vast) that ‘measuring the wealth of nations’ is now the subject of a vast technical literature (see in particular Maddison, 1995a; Shaikh and Tonak, 1994; Coates, 1995a). But that literature notwithstanding, it is clear that, even among advanced capitalist economies, patterns of economic performance have varied significantly over the postwar period as a whole, and that they have varied no matter how that performance is measured. Whether we use discrete indicators (such as output growth, the productivity of capital or labour, trade share, investment, or living standards) or simply competitive league tables, the picture remains broadly the same. It is a picture of initial postwar US economic supremacy (a supremacy shared in the late 1940s by the UK as the capitalist bloc’s second major economic power); it is a picture of subsequent convergence and catch-up by a select group of northern European and Asian economies; and it is a picture of recent unexpected economic turbulence.

If we take the figures in table 1.1 as our starting point, they confirm that per capita income in the US in 1950 was significantly higher than elsewhere in the world system, and that in 1950 at least, living standards in the UK were only rarely exceeded in Western Europe, and then only just. They also show that forty years later average per capita income in the US was still higher than elsewhere (although the margin of difference was much less), that living standards in Japan were by then close to North American standards, and that those in the UK had slipped well behind average levels in most of northern Europe. The figures also show that what links the two dates are spectacularly different overall growth performances: an increase of per capita income in the US and UK of 230 per cent compared with a change in GDP per head of more than 900 per cent in Japan and Taiwan and of around 500 per cent in West Germany and Italy.

Statistics are, of course, highly malleable, and in consequence have to be approached with a developed sensitivity to the manner of their construction and to their framework of underpinning assumptions. In table 1.1 the choice of 1950 as the base year is critical: it was a time when the former Axis powers were still suffering extreme postwar dislocation and the Allies were enjoying a brief period of unchallenged world supremacy. The choice of end year (1994) is also significant, marking the moment when the Japanese economy had settled firmly into its first major postwar recession and the US and UK economies had begun their prolonged 1990s period of growth and job creation. The choice of base level is equally important: spectacular growth rates are much easier to achieve if the starting point is low (as it was with Japan in 1950), if economies are at different points in their own growth histories (as was visibly the case with South Korea), and if economies lie ahead with superior technologies that can be copied and with markets that can be raided (as did the US and the UK). There is a dimension – actually a very large dimension – of simple ‘catch up and convergence’ tucked away in the figures of table 1.1 (whose importance and significance we shall discuss fully in chapter 6); but there are real changes tucked away there too, changes that cannot be simply explained – and explained away – in such a fashion. Three sets of such changes deserve our particular attention.

Table 1.1 Real GDP per person, 1950–1994 (international dollars at 1990 values)

Source: Crafts, 1997a: 15

1 The first is the significant weakening in the relative positions of both the US and the UK economies over the period as a whole, the gap between levels of performance in the US economy and those in other leading capitalist economies diminishing over time, and the UK economy slipping down a variety of league tables on such things as output, productivity, investment and living standards, particularly before 1979.

2 The second is the remarkable surge of growth in a number of northern European economies (including the German, Benelux and Scandinavian economies) in the 1950s and 1960s, the more prolonged growth of the Japanese economy and the recent growth surge of the Asian Tiger economies – a surge that has effectively added a new regional grouping of major capitalist industrial economies to the regional groupings in north America and northern Europe laid down before 1945.

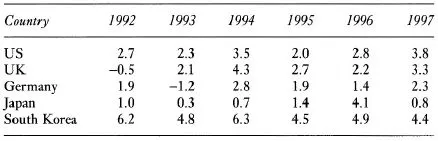

3 The third (hinted at in table 1.1, but clearly evident in table 1.2) is the revival of the post-1979 UK economy relative initially to the German and recently even to the Japanese economies, and the revival too of the US economy’s capacity to generate growth and employment. In fact, by as early as 1994 the US had replaced Japan as the world’s ‘most competitive nation’ in the league tables produced by the Geneva-based World Economic Forum, Japan having occupied the top position for the previous seven years (Financial Times, 6 September 1995). All this before the more provisional statistical data covering the second half of the 1990s began to document the scale of the post-1992 Japanese recession, the post-1997 East Asian economic ‘crisis’ and the slowing down of productivity, growth and employment rates in most (although by no means all) of the northern European economies. These were all developments that restored some degree of international competitiveness to some economies (the UK’s perhaps, the US more certainly), which had been widely seen before 1980 as weakening (and even as potentially terminally flawed).

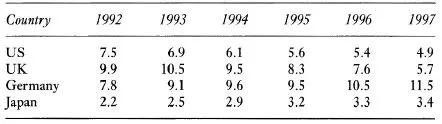

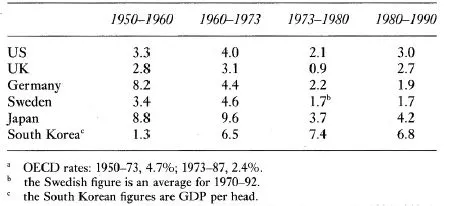

Indeed each of the major capitalist economies has a slightly different postwar growth story to tell, as table 1.4 attempts to indicate. The best decades for the West German economy, in terms of economic growth, were definitely those before 1973. After the first oil crisis, West German growth rates settled back to nearer the average for the OECD as a whole. The Swedish economy also had its best decades before 1973; but it then settled into a growth rate that was lower than the OECD average. The Japanese economy, by contrast, sustained its high-growth performance relative to that average right up to 1992, although in its case also the years of truly spectacular rates of growth were over by 1973. The ‘Asian growth miracle’ after 1973 occurred elsewhere, in places such as South Korea. By contrast, the growth performance of both the US and the UK economies was more sluggish throughout, and was particularly dire in the years between the first oil crisis and the second (1973–1979). In comparative terms, the best growth decade for those economies was the 1990s. Certainly the UK economy then managed to pull itself out of the long recession into which it had settled between 1989 and 1992, to perform its own small ‘catch up’ operation on its main European rivals; both it and the US economy spent most of the 1990s lowering their officially recorded levels of unemployment as unemployment rose both in the newly united Germany and in Japan.

Table 1.2 Annual percentage change in GDP, 1992–1997

Source: National Institute Economic Review, 3/98: 121

Table 1.3 Rates of unemployment, 1992–1997 (seasonally adjusted per cent of total labour force, by national definition)

Source: National Institute Economic Review, 3/98: 121

Table 1.4 Real GDP growth, 1950–1990 (average annual percentage change)a

Sources: Giersch et al., 1992: 4; Pilat, 1994: 8; Henrekson et al., 1996: 243–4; Henderson, 1990: 276, 279

The question of capitalist models

It is with the origins and determinants of these key features of the postwar economic growth story that the text which follows is primarily concerned; and it is so for at least three distinguishable sets of reasons. The first is that the causes of that growth pattern are academically contentious, and that those academic disputes trigger very different bodies of advice for politicians and civil servants committed to the pursuit of growth. Which explanation is correct, therefore, is of immense political (and not just academic) interest. The second is that behind these academic debates and policy recommendations lie real disagreements about the viability of particular models of capitalist organization and their associated political projects, and hence real issues about desirable and attainable futures. The rights of workers in particular rise and fall with the viability of these underlying models. And the third is that economic growth touches so many aspects of social life, and does so regardless of the political projects within which it occurs, that its achievement is a prerequisite for the protection of so much that is of importance to us all, workers or not.

At the core of the contemporary debate on why growth rates differ stands a neo-liberal economic orthodoxy. In that dominant paradigm, economic growth is explained as a consequence of the freeing of market forces and the associated development of appropriate factors of production; and differences in growth performance are explained as by-products of the degree of market freedom achieved and of the resulting differences in factor quantity and quality. As is explained in more detail in the Appendix, neo-liberalism has both an ‘old’ and a ‘new’ face, but in both these forms neo-liberal explanations of economic performance have never been entirely without challenge. To their right has long stood a conservative strand of argument uneasy with the social consequences of untrammelled markets, an unease normally articulated without the support of a complete and distinctive theory of how capitalist economies grow, and one prone to emphasize the pivotal role of non-market factors (of trust and culture) in explaining different patterns of economic growth. To their left have long stood both centre-left and Marxist explanations of how capitalist economies perform: explanations of different growth rates that either emphasize discrete non-market-based factors as key shapers of the way markets operate or point to the manner in which market-based interactions are qualitatively transformed by their insertion into different capitalist-based class systems and the resulting social structures of accumulation. There was a time (throughout the 1960s, and in certain circles well into the 1970s) when centre-left arguments were the dominant ones, pushing liberal views of markets off centre-stage; but since the ‘crisis of Keynesianism’ in the 1970s liberalism has returned apace – and economic policy now is shaped by a much narrower and more right-wing range of views than was conventional two decades ago.

As we shall see in more detail as the argument unfolds, there is a close affinity between the policy packages adopted in the pursuit of economic growth and wider bodies of economic theory. Advocates of market-based capitalism tend to draw on the arguments of neo-classical economics in defence of their case. Advocates of ‘third way’ packages tend to empathize with ‘new growth theory’ (as was once famously admitted by Gordon Brown, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the UK’s New Labour Government after 1997). Certain conservative-inspired popularizers of more trust-based forms of capitalism (Fukuyama in particular) tend to treat neo-classical economics as essentially correct but limited, and to talk of ‘a missing twenty per cent of human behaviour about which neo-classical economics can give only a poor account’ (Fukuyama, 1995: 13). And more centre-left advocates of German and Japanese modes of capitalist organization tend, as we shall see, to mobilize Schumpeterian or post-Keynesian understandings of the growth process to sustain their preference for cartelized forms of corporate organization and proactive government spending. These particular economic theories are therefore yet another ‘academic specialism’ with which the general student of politics now needs to be familiar. (They are surveyed briefly in the Appendix, to assist those readers whose knowledge of economic theory is currently limited.)

For it is hard to overstate the contemporary political importance of the current academic debate on why growth rates differ, or to overestimate the centrality of the ‘labour question’ to that debate. As we shall see later, both ‘old’ and ‘new’ versions of neo-liberal growth theory ultimately subscribe to the view that growth depends on competitiveness, and that competitiveness depends in large part on the control of labour costs. ‘Old growth theory’ points the finger of responsibility for labour costs at ‘inflexibilities’ created by trade union organization and power. ‘New growth theory’ tends to shift the focus of responsibility away from trade unionism towards issues of labour skills and training, and even on occasions dabbles sympathetically with the more conventional centre-left argument that the key to labour-market flexibility is a set of trust-based industrial relationships guaranteed by extensive worker rights and trade union powers. Yet within that entire policy spectrum – from those who would achieve economic growth by cutting trade union powers to those who would achieve economic growth by increasing them – the relationship of labour power to international competitiveness is still seen as central. More radical voices still problematize other social actors and processes, as we shall see. The nature of capital, the force of culture, the capacities of the state – these too have a presence in the contemporary debate on why growth rates differ. But the central preoccupation of most academic commentators and contemporary policy-makers is with questions of labour power. In most policy-making circles these days, labour power and international competitiveness are invariably seen as incompatible, and policy is inexorably directed at reducing the first in order to enhance the second.

This is why one of the main research questions underpinning this study is whether ‘flexible’ labour markets are a necessary condition for successful capital accumulation: whether they were in the immediate past, and whether the new conditions of intensified global competition now make the erosion of trade union rights and levels of labour remuneration even more vital to the achievement and retention of international competitiveness. We need to know whether it was always necessary in the past, and is always necessary now, to cut wages, intensify work routines and reduce workers’ and trade union rights, if the economic growth of a particular economy is to be sustained in the face of competition from companies based abroad. As we shall see in more detail in chapter 4, that was certainly the thrust of the neo-liberal project developed in the UK by Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s; and even now, when UK politics is dominated by the ‘third way’ thinking of New Labour, it remains conventional to argue both that UK labour markets have to remain flexible if competitiveness is to be sustained and that European labour markets have to become more flexible if unemployment is to be reduced. The Thatcherite solution to the diminished competitiveness of European welfare capitalism was to dismantle welfare rights. The Blairites talk only of reforming those rights: but in practice the direction of policy is similar. Because it is, particularly the European-based debate about how to encourage economic growth in the new millennium is in essence a debate about the viability of a particular capitalist model. It is a debate about the future of welfare capitalism, as that has been understood and lived by northern European labour movements since 1945.

Ultimately this should not surprise us, for in fact each of the major positions in the contemporary debate on why growth rates differ among advanced capitalist economies has historically been associated with a distinct set of attitudes to the viability or otherwise of discrete models of capitalism. Indeed the varying fortunes of economies thought to exemplify those models have shaped (and continue to shape) the popular (and to a degree even the academic) discussion of contemporary growth strategies in important ways, the confidence of their advocates ebbing and flowing as their particular exemplars prosper and decline. So enthusiasts for market-led capitalisms lost ground to their opponents as the United States’ competitive advantage was eroded – first by Western-European-based companies and then by Japanese-based ones – in the 1970s and 1980s; and in the same manner critics of market-led models had their confidence shaken by the growing sclerosis of Western European economies in the 1990s and by the ‘crisis of the Asian model’ which broke in the summer of 1997. For there can be no doubting the close fit that exists between different theories of economic growth and the institutional arrangements characteristic of different capitalist models. Broadly speaking, neo-liberal scholarship tends to favour Anglo-American practices, in which neither the state nor the unions have a significant economic role or voice. Conservative scholarship tends to favour developmental models of the East Asian kind, or occasionally the French kind, in which political institutions work closely with private capital in the pursuit of growth (Barnett, 1986; Albert, 1993; Fukuyama, 1995). Centre-left scholarship invariably has a penchant for consensual models of a Scandinavian or German hue, in which trade unions figure as a junior governing partner, and extensive welfare rights underpin private economic relationships, while Marxist scholarship, which in the West has long eschewed centrally planned economic models of Soviet derivation, tends predictably to see deep and irresolvable contradictions in capitalism however organized, and therefore calls down a plague on all these houses.

In the broadest sense the choice of model in that clash of political projects can be (and should be) reduced to one of three: to a choice between a market-led form of capitalism and two differing forms of capitalist organization which are often presented by their advocates as more trust-based than market-led, one in which state power is of central importance to local capital accumulation, and one built around an explicit compact between capital, labour and the state. It should be said, in passing, that the relevant academic literature is more profligate that that (for a full survey, see Coates, 1999b). It is replete with models differentiated either by geographical location (the ‘Scandinavian model’, the ‘Asian model’ and the like) or by institutional variation (bank-based systems versus credit-based, ‘individualistic’ versus ‘communitarian’ value systems, ‘coordinated’ versus ‘non coordinated’ forms of labour mar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Guide to Country Story Lines

- 1 Capitalist Models and Economic Growth

- Part I Capitalist Models: The Arguments

- Part II Capitalist Models: The Evidence

- Part III Conclusion

- Appendix: Theories of Growth

- References

- Index