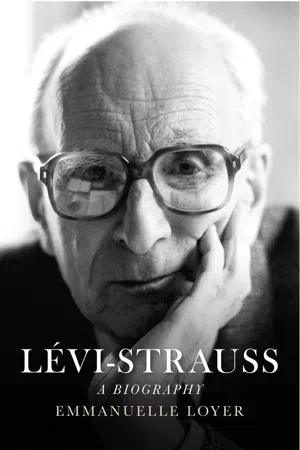

Lévi-Strauss

A Biography

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Lévi-Strauss

A Biography

About this book

Academic, writer, figure of melancholy, aesthete – Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) not only transformed his academic discipline, he also profoundly changed the way that we view ourselves and the world around us. In this award-winning biography, historian Emmanuelle Loyer recounts Lévi-Strauss's childhood in an assimilated Jewish household, his promising student years as well as his first forays into political and intellectual movements. As a young professor, Lévi-Strauss left Paris in 1935 for São Paulo to teach sociology. His rugged expeditions into the Brazilian hinterland, where he discovered the Amerindian Other, made him into an anthropologist. The racial laws of the Vichy regime would force him to leave France yet again, this time for the USA in 1941, where he became Professor Claude L. Strauss – to avoid confusion with the jeans manufacturer. Lévi-Strauss's return to France, after the war, ushered in the period during which he produced his greatest works: several decades of intense labour in which he reinvented anthropology, establishing it as a discipline that offered a new view on the world. In 1955, Tristes Tropiques offered indisputable proof of this the world over. During those years, Lévi-Strauss became something of a French national monument, as well as a celebrity intellectual of global renown. But he always claimed his perspective was a 'view from afar', enabling him to deliver incisive and subversive diagnoses of our waning modernity. Loyer's outstanding biography tells the story of a true intellectual adventurer whose unforgettable voice invites us to rethink questions of the human and the meaning of progress. She portrays Lévi-Strauss less as a modern than as our own great and disquieted contemporary.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Yesterday’s Worlds (…–1935)

1

The Name of the Father

But so long as a great name is not extinct it keeps in the full light of day those men and women who bear it; and there can be no doubt that, to a certain extent, the interest which the illustriousness of these families gave them in my eyes lay in the fact that one can, starting from to-day, follow their ascending course, step by step, to a point far beyond the fourteenth century, recover the diaries and correspondence of all the forebears of M. de Charlus, of the Prince d’Agrigente, of the Princesse de Parme, in a past in which an impenetrable night would cloak the origins of a middle-class family, and in which we make out, in the luminous backward projection of a name, the origin and persistence of certain nervous characteristics, certain vices, the disorders of one or another Guermantes.Marcel Proust1

A halo around the name

‘With a name like yours!’

‘Claude Lévi, aka Lévi-Strauss’

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Worlds of Claude Lévi-Strauss

- Part I: Yesterday’s Worlds ( –1935)

- Part II: New Worlds (1935–1947)

- Part III: The Old World (1947–1971)

- Part IV: The World (1971–2009)

- Works by Lévi-Strauss

- Archives Consulted

- Abbreviations of Works by Lévi-Strauss

- Index

- End User License Agreement