I waited forty-seven years before going to see the spot where my brother Ernesto Guevara was murdered. Everyone knows he was killed by a coward’s rifle on 9 October 1967 in a shabby classroom of the village school in La Higuera, an isolated hamlet in South Bolivia. He had been captured the day before at the bottom of the Quebrada del Yuro, a bare ravine where he had entrenched himself after realizing that his sparse band of guerrillas, weakened by hunger and thirst, was surrounded by the army. They say he died with dignity and that his last words were ‘Póngase sereno y apunte bien. Va a matar a un hombre’ (‘Calm down and take good aim. You’re going to kill a man’). Mario Terán Salazar, the unfortunate soldier appointed to do the dirty work, was shaking. True, Che had for eleven months been public enemy number 1 of the Bolivian army, perhaps even of the entire American continent, but he was a legendary opponent, a mythical figure covered in glory, known for his sense of justice and fairness and also for his immense bravery. What if this Che, gazing unblinkingly at him with his big deep eyes without seeming to judge him, really was the friend and defender of the humble rather than the blood-stained revolutionary portrayed by his superiors? What if his disciples, said to be loyal to a fault, would one day decide to track him down and avenge Che’s death?

Mario Terán Salazar had needed to get drunk before he could find the courage to pull the trigger. When he saw Che sitting calmly, waiting for the inevitable, he rushed out of the classroom, bathed in sweat. His superiors forced him to return.

My brother died standing. They wanted him to die sitting down, to humiliate him. He protested – and he won this last battle. Among his many qualities, or talents, he could be very persuasive.

I bought a new pair of sneakers to get down to Quebrada del Yuro. It’s a deep gorge, falling away abruptly behind La Higuera. It was very difficult, very painful for me to be here. Painful, but necessary. This pilgrimage was a project I’d been carrying around with me for years. It had been almost impossible to come here any earlier. In the first years following Che’s death, I was too young, not quite prepared psychologically. Then Argentina turned fascist and repressive and I languished for nearly nine years in the jails of the military junta that seized power in March 1976. I learned to lie low: in the political climate of my country, it was for many years dangerous to be associated with Che Guevara.

Only my brother Roberto came to the area in October 1967, sent from Buenos Aires by the family to try and identify Ernesto’s body once the news of his death had been announced. He returned deeply shocked and bewildered: by the time he arrived in Bolivia, the remains of our brother had vanished. The Bolivian soldiers led Roberto a merry chase, sending him from one city to another, changing their story every time.

My father and my sisters Celia and Ana Maria never had the strength to make the journey. My mother had succumbed to cancer two years earlier. If she had not already been in the grave, Ernesto’s assassination would have finished her off. She adored him.

I drove here from Buenos Aires with some friends. A journey of 2,600 kilometres. In 1967, we did not know where Ernesto was. He had left Cuba in the greatest secrecy. Only a few people, including Fidel Castro, knew that he was fighting for the liberation of the Bolivian people. My family was lost in conjectures, imagining him to be on the other side of the world, in Africa maybe. In reality, he was only thirty hours away from Buenos Aires, where we lived. We would learn years later1 that he had travelled via the Belgian Congo where, with a dozen or so black Cubans, he had gone to support the Simba rebels.

On the crest of the ravine, I’m approached by a guide. He doesn’t know who I am and I don’t want to reveal my identity. He demands that I give him some money to show me where Che was captured – the first sign that my brother’s death has been turned into a business venture. I am outraged. Che represents the complete opposite of sordid profit. The friend who has accompanied me here is furious; he can’t stop himself from telling the guide who I am. How dare this guide try to get money out of Che’s brother just when he is coming to pay homage for the first time at the site of his fatal defeat? The guide steps back with reverence and stares at me wide-eyed. It’s as if he has just seen an apparition. He apologizes profusely. I’m not listening. I’m used to it. Being the brother of Che has never been a trivial matter. When people learn who I am, they’re dumbstruck. Christ can’t have any brothers or sisters. And Che is a bit like Christ. In La Higuera and Vallegrande, where his body was taken on 9 October to be displayed to the public before disappearing, he became San Ernesto de la Higuera. The locals pray before his image. I generally respect religious beliefs, but this one really bothers me. In the family, since my paternal grandmother Ana Lynch-Ortiz, we haven’t believed in God. My mother never took us to church. Ernesto was a man. We need to pull him down off his pedestal, give life to this bronze statue so we can perpetuate his message. Che would have hated being turned into an idol.

I begin the descent down to the fateful place with a heavy heart. I am struck by the bareness of the ravine. I expected to find dense vegetation. In fact, except for a few dry, thick shrubs, nature is almost like a desert here. I now find it easier to see how Ernesto could have ended up caught like a rat in a trap. It was practically impossible to stay out of sight of the army, which had encircled the Quebrada the day before.

I reach the place where he was wounded by a gunshot in his left thigh and another in his right forearm. I start with amazement. In front of the puny tree against which he had leaned on 8 October, the dry ground is covered by a star, cast in concrete. It marks the exact place where he was sitting when he was discovered. A profound anguish takes hold of me. I’m overwhelmed by doubts. I feel his presence. I pity him. I wonder what he was doing there, alone. Why wasn’t I with him? Of course I should have been with him. I was always a militant, too. He was not only my brother, but my comrade in struggle, my model. I was only twenty-three, but that is no excuse: in the Sierra Maestra in Cuba – the mountain range where the armed struggle started during which

Fidel Castro appointed Che Comandante, and where he distinguished himself – some of the fighters were only fifteen! I didn’t know he was in Bolivia, but I should have known! I should have stayed with him in Cuba in February 1959, and ignored my father’s veto.

I sit down, or rather I slump down onto the place where he had sat. I can still see his handsome face, his hypnotic, inquisitive gaze, his mischievous smile. I can hear his infectious laughter, his voice, his indefinable inflection: with the years he spent in Mexico and then in Cuba, his Spanish had become a mixture of three accents. Did he feel alone, vanquished?

Some of the questions I ask myself have a practical side to them. Others are purely sentimental. Che was not alone, but supported by six fighters who were arrested with him. Could I have helped him escape? That day, five other companions, including Guido ‘Inti’ Peredo, did after all manage to escape the ambush.2 Why didn’t he? I reconstruct the chain of events that led to the death of my brother. Was Che betrayed? If so, by whom? There are several hypotheses, but as that’s all they are, I prefer not to dwell on them. Ernesto was fighting under the name Ramón Benítez. They say he chose the name Ramón in honour of the short story ‘Meeting’ by Julio Cortázar, which recounted the adventures of a group of revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra. His presence was shrouded in mystery. On the basis of information provided by the CIA – which had brazenly set up an HQ in the presidential palace of René Barrientos in La Paz – the Bolivian government suspected that Ernesto Guevara was commanding the Ñancahuazú army, without having any proof of this.

Until, that is, the Argentinian Ciro Bustos, arrested in the scrub after being authorized by Che to abandon the insurgency, provided them with an identikit portrait of Che, under the threat of spending the rest of his days in prison.

As I climb back up the ravine, I feel devastated, emptied. An unpleasant surprise is waiting for me in La Higuera. As I enter the hamlet to go and pay homage in the school where Ernesto was killed, a woman breaks away from a group of Japanese tourists and pounces on me. She has just learned from another Japanese woman, a journalist, that Che’s brother is here. She cries, and mumbles: ‘Che’s brother, Che’s brother’. She asks me most politely to pose for a photo with her. I have no choice but to agree and comfort her. This Japanese woman apparently considers me to be a reincarnation of Che. I am both disturbed and touched. Almost fifty years after his death, my brother is more than ever present in the collective memory. I’m certainly not Ernesto, but I can, and must, be a conduit for his ideas and his ideals. His five children barely knew him. My sister Celia and my brother Roberto categorically refuse to talk. My sister Ana Maria died of cancer, like my mother. I am seventy-two years old. I can’t waste any time.

The school where Ernesto spent his last night has undergone a few transformations. The wall that separated the two classrooms has been knocked down. The walls are covered with pictures and posters depicting Che’s last hours. The chair he occupied when Mario Terán Salazar came to kill him is still there. I imagine my brother sitting there, waiting for his death. It’s very difficult.

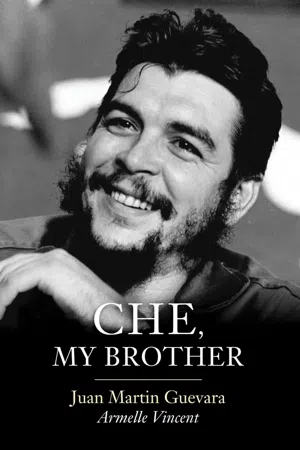

On the village square stands a large white bust sculpted by a Cuban artist, based on the famous photo by Alberto Korda, Guerrillero heroico. This bust, behind which a white cross looms, also has a turbulent history. It was put up in early 1987 and quickly removed by a commando from the Bolivian army, to be replaced by a plaque in memory of the soldiers who were victims of guerrilla warfare. It resumed its place twenty years later, accompanied by a four-metre-high sculpture standing at the entrance to the hamlet. For years, the people of La Higuera and Vallegrande were terrorized. No one dared speak of Che: so as to eradicate all traces of the passage of this ‘subversive’,3 the Bolivian government had banned all mention of his name. In response to the imposed silence, legends inevitably began to be forged. At the time of his capture, the peasants of the Aymara community who inhabit the area had no awareness of the importance of this prisoner. They never saw any strangers, and barely spoke any Spanish. After Che’s death, hordes of journalists descended on their village. Until 9 October 1967, no one had ever heard of La Higuera. On 10 October, thirty-six planes lined up on the improvised runway in Vallegrande, sixty kilometres away. The natives started to realize that a significant event had occurred, that this prisoner was not just any prisoner.

Ernesto’s body was taken to Vallegrande on a stretcher mounted onto the landing gear of a helicopter. The Bolivian military decided to display it in the laundry at the bottom of the garden of the small local hospital, for seventeen hours. They wanted to make an example of him; to show that the whole crew of ‘subversives’ like this Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara would be annihilated. Che was dead, dead, dead! This pathetic end was to serve as a lesson to the people. They should never stray into such a lamentable adventure, one that was inevitably doomed to failure.

His half-naked body was placed on a cement slab. He was barefoot, his eyes open – even though it was said that a priest had closed them in La Higuera . . . Some have compared the image of my tortured brother to the painting known as The Lamentation of Christ by the Italian Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna. The resemblance is uncanny, but it means nothing. Some witnesses said that Che’s eyes followed them while they wandered around his body. Others say that the doctor – a secret admirer – responsible for washing his body wanted to embalm it, but didn’t have enough time and so took his heart to keep it in a jar. The same doctor, it is claimed, took two death masks, the first in wax and the second in plaster. One nurse was surprised by the peaceful expression on Ernesto’s face, which contrasted strangely with the other guerrillas who were killed: their faces were marked by suffering and anguish. I don’t believe these idiotic stories. They all tend towards the same goal: to turn Che into a myth. It is this myth that I intend to fight, by giving back to my brother his human face.

After 9 October, fifteen soldiers remained stationed in La Higuera for a year. They told the farmers that they were there to protect them from Che’s accomplices who would inevitably come to kill them in vengeance for his death. For it was these same peasants, wasn’t it, who had betrayed Che.

In this way, a cult was born, amid whispers and fears.

The shameful trade that has developed around Che horrifies me. Er...