- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

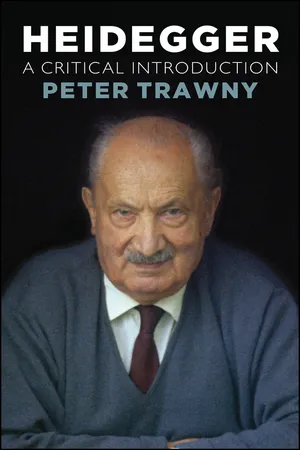

Martin Heidegger is one of the most influential figures of twentieth-century philosophy but his reputation was tainted by his associations with Nazism. The posthumous publication of the Black Notebooks, which reveal the shocking extent of Heidegger's anti-Semitism, has only cast further doubt on his work. Now more than ever, a new introduction to Heidegger is needed to reassess his work and legacy.

This book by the world-leading Heidegger scholar Peter Trawny is the first introduction to take into account the new material made available by the explosive publication of the Black Notebooks. Seeking neither to condemn nor excuse Heidegger's views, Trawny directly confronts and elucidates the most problematic aspects of his thought. At the same time, he provides a comprehensive survey of Heidegger's development, from his early writings on phenomenology and his magnum opus, Being and Time, to his later writings on poetry and technology. Trawny captures the extraordinary significance and breadth of fifty years of philosophical production, all against the backdrop of the tumultuous events of the twentieth century.

This concise introduction will be required reading for the many students and scholars in philosophy and critical theory who study Heidegger, and it will be of great interest to general readers who want to know more about one of the major figures of contemporary philosophy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The “Facticity of Life”

“There was hardly more than a name, but the name traveled all over Germany like the rumor of the hidden king.”1Hannah Arendt

Phenomenology and hermeneutics

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface to the English Edition

- Introduction

- 1: The “Facticity of Life”

- 2: The “Meaning of Being”

- 3: The “History of Being”

- 4: The “Essence of Technology”

- 5: Reverberations

- Biographical Facts in Historical Context

- Bibliography

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app