Mariana, 5 November 2015

In this mining town in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, the walls of two reservoirs containing the waste water from an iron mine burst, causing 60 million cubic metres of heavy-metal-containing mud – enough to fill 25,000 Olympic swimming pools – to flood the neighbouring community of Bento Rodrigues and enter the Rio Doce.3 Caused by a minor earthquake, according to the mine operator Samarco Mineração SA, the mud flowing out of the reservoir engulfed surrounding villages and some of their inhabitants. Three-quarters of the 853-kilometre-long ‘Sweet River’ became a toxic mix of iron, lead, mercury, zinc, arsenic and nickel residues, abruptly cutting off some 250,000 people from access to clean drinking water. After fourteen days, the tide of red mud reached the Atlantic coast and flowed out into the ocean, leaving behind a devastated ecosystem. At the Paris Climate Change Conference a few weeks later, the Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff described it as the worst environmental disaster in her country's history.

However striking the pictures may be of the mud-covered landscape and expired animals, of the dead river and its estuary, coloured a dirty red, the case of the Rio Doce is depressing not because of its uniqueness, but rather because of its perverse ordinariness. Rio Doce is everywhere. The causes of the ‘accident’, the way it was handled, its predictability and the reactions to it are typical of a state of affairs that exists worldwide. It is not only typical of an economic and ecological world order in which the opportunities and risks of social ‘development’ are systematically distributed in an uneven fashion. It amounts to a textbook example of the ideal type – the local, regional and global business-as-usual approach to the costs of the industrial-capitalist social model.

What happened at the Rio Doce was a perfectly normal catastrophe – and one that was waiting to happen. For many years, similar incidents have been occurring repeatedly, in Brazil and in other countries around the world with plentiful natural resources. Given the global division of labour, these countries are forced to exploit these resources as an economic strategy – and they do so in an intensive and sometimes reckless manner. The expression ‘they do so’, however, requires some qualification, because in many cases the business operations are contracted out to transnational corporations. In 2011, Brazil mined 400 million tons of iron ore, making it the third-largest producer after China and Australia. The formerly state-owned company Companhia Vale do Rio Doce was privatized in 1997 and renamed Vale SA. Alongside the British–Australian corporations Rio Tinto Group and BHP Billiton, it is one of the three largest mining companies in the world and the world's largest iron ore exporter, with a market share of 35 per cent.4 Together with BHP Billiton, it is the co-owner of the mine in Mariana through its subsidiary Samarco.

Samarco initially announced that the sludge from the burst reservoirs was not toxic and consisted mainly of water and silica. This announcement soon turned out to be false, as did the claim that the accident had been caused by earth tremors. More likely, the causes are to be found in familiar features of the administrations of ‘third-world countries’, namely corruption, clientelism and lack of controls. And, indeed, all these appear readily evident at first glance: there had been security concerns about the safety of the tailings dam for a long time, noted by the public prosecutor's office as early as 2013. In their criticism, the authorities also mentioned the immediate risk for the village of Bento Rodrigues, pointing out that no preventive measures of any kind had been taken to protect its inhabitants. The safety reviews ordered by Minas Gerais, the state with the largest ore-mining area in Brazil, were carried out not by independent experts but by members of the company itself. Almost at the same time as the dam burst, a commission within the senate, the upper house in the Brazilian parliament – where the mining lobby can always count on political support – voted for ‘more flexibility’ in the regulation of mining operators by the authorities.

So, is it all a question of underdeveloped governance, failing institutions, a ‘non–Western’ political culture? Perhaps. The other side of the chronicle of this ‘accident’ foretold is that, only a short time before it occurred, the physical stress placed on the dams had been significantly increased. In spite (or because) of the recent decline in world market prices, the two major corporations had increased the output of the Samarco mine to 30.5 million tons, a rise of almost 40 per cent compared with the previous year. In the case of Mariana, this market-flooding strategy had led to a large increase in waste from the mine and, as a result of this, the subsequent flooding of the surrounding area. Incidentally, the third and largest iron mine retention basin in Mariana is also showing dangerous cracks in its walls. And these are only three of 450 dams that hold back mining and industrial waste water in Minas Gerais alone. Around a dozen of these toxic reservoirs threaten the Rio Paraíba do Sul and hence, indirectly, the supply of drinking water to the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro and its 10 million inhabitants.

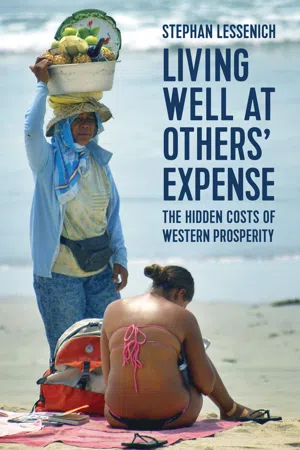

What happened at the Rio Doce is a disaster for nature – and for the people living in and off it – yet it was not a natural disaster. The background to it is anything but ‘natural’. Its causes are to be found in the structure of the world economic system: in the development models – which are influenced by this system – of countries rich in natural resources; in the global market strategies of transnational corporations; in the hunger for resources of rich industrial countries, and in the consumer habits and lifestyles of their inhabitants. What happened in Mariana, Minas Gerais, Brazil, and what is happening there every day, beyond the accidents and disasters reported by the media, is not caused by local conditions – at least not exclusively, and only peripherally, in the literal sense. What, from our perspective, happens at the ‘periphery’ of the world, at the outposts of global capitalism, is connected with the central hub – or, to be more precise, with the social conditions in those regions that believe themselves to be the centre of the world and that use their position of power in the global economic and political systems to dictate the rules that others must obey and whose consequences are felt elsewhere.

One of these rules – maybe even the most important one – says that, after ‘incidents’ such as the one that occurred in Mariana, life should return to normal as soon as possible. This does not apply only at the local level, where resistance to the mining industry is difficult to organize, for obvious reasons: whether they want to or not, the people of Minas Gerais depend on it. Four out of five households in Mariana rely on the mines for their existence. According to the mayor, Duarte Júnior, if they were to be closed, the entire village might as well be boarded up. In the wake of the ‘disaster’, people repeatedly took to the streets – not in protest against the mine's operators, but to demand that the mine start operating again as soon as possible. At the same time, there were, of course, ‘experts’, who sounded the all-clear or warned against unfounded environmental hysteria. Paulo Rosman, Professor of Coastal Engineering at the University of Rio de Janeiro and author of a hastily written report on behalf of the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment, declared that the Rio Doce was ‘temporarily dead’, bu...