1

Traces of Violence, Rhetoric of Consensus, and Subjective Dislocations

The first governmental administration of Chile’s Transition to democracy (led by Patricio Aylwin in 1990) constructed itself on a consensus-based model of a “democracy of agreements.” This model signaled a shift from politics as antagonism (the drama of the conflict was exacerbated by the polarizing confrontation between the dictatorship and its opponents) to politics as transition (the formation of agreements and the technicalities of negotiations conducted by new institutional authorities and the entrenched powers that remained hidden in the shadows, continuing to block the path toward democratic recovery).1 The “democracy of agreements” made consensus its normative guarantee, its operational code, its de-ideologizing ideology, its institutional rite, and its discursive victory.

What kind of excesses did this new rhetoric of consensus seek to control by attempting to force unanimity, through formally and technologically rationalized democratic agreements, onto the voices of those who fought against the dictatorship? Excessive vocabularies (the dangerous riot of words disseminating heterodox meanings in order to name the hidden/repressed that trespasses into the networks of official discourse); excessive bodies and experiences (the discordant modes in which social subjectivities break the identifying lines drawn by political scripts or advertising spots); excessive remembrances (the tumultuous reinterpretations of a past full of aspirations and defeats – of Unidad Popular [Popular Unity] and the military coup of 1973 – that keep the memory of this history open to an incessant struggle of readings and meanings).

Memory and disaffection

The recuperation and normalization of the democratic order in Chile was an attempt to exorcise the ghosts of the multiple ruptures and dislocations of life produced by the coup and the military dictatorship, employing the consensus method to neutralize the differentiating counterpoints, antagonistic postures, and polemical demarcations of conflicting meanings through a politico-institutional pluralism that assumes a noncontradictory diversity. This nonconflictive diversity is a passive sum of differences that are almost indifferently juxtaposed, and it avoids any confrontation between these differences so as to forestall any disruption of a neutral reconciliation of opposites. The terms pluralism and consensus were summoned by the architects of the democratic transition to represent a new society in which the official channels of expression only bothered to honor diversity when it was in line with the Transition’s carefully calculated agreements, thus avoiding any attempt to reckon with the ideological conflicts of the past.

Consensus, the paradigm of political legitimacy, was established in order to normalize the heterogeneous plurality of the social. This was a model that disciplined antagonisms and confrontations and established rules designed to protect macro-institutional agreements. The Transition’s official consensus excluded from its national protocol the memory of conflicts that took as their basis and passion the internal struggle around the meaning of the “transition to democracy,” apparently forgetting that all supposedly neutral social objectivity is a threatened objectivity. It “necessarily presupposes the repression of that which is excluded by its establishment.”2 The Transition’s official discourse disregarded the negative force of the excluded and prevented the polemical and controversial vitality of the repressed from disturbing the limits of normalized politics. To avoid impeding the regulation of the pre-established connections between memory, violence, and democracy, the Transition suppressed from its repertoire of accepted meanings the inconvenient memory of what preceded and exceeded the politico-institutional consensus.

Claiming that “consensus is the highest stage of forgetting,” Tomás Moulian alludes to the “whitewashing” that, during the Transition, began to sweep away sharp contradictions about the historical value of the past and to smooth over disagreements about the objectives of a transitional present in which “politics no longer exists as a struggle of alternatives, as historicity.” During the Transition, politics functioned instead as a “history of small variations, adjustments, changes in aspects that do not compromise the global dynamic.”3 These “small variations, adjustments, and changes” heralded a society with a predetermined future. This democratic realism was an attempt to move away from the risks of indeterminacy at the cost of further lowering the expectations of a social body that no longer felt attracted to the once radiant field of decisions and historical wagers.

The official administrators of consensus successfully downplayed the marks of violence that have always been attached to the name “post-dictatorship” in order to downplay the seriousness of the meaning conveyed in their staging of the “facts,” neutralizing it with the professional vocabulary of “transition.” The rhetoric of consensus decreed that nothing intolerable, nothing insufferable, should ruin the spirit of wanting to facilitate the reconciliation of society. During the Transition, the political meanings of memory were once again rendered inoffensive through the use of words stripped of both emotion and fear. Even if the Transition’s discourse occasionally alluded to memory as conflict, it was not able to express its agony. Moreover, immediate suspicion was generated by the symbolic density of any testimonial narrative whose figurative language could, in spite of this catastrophe, still generate an emotional outpouring of memory that altered the meticulously studied formulism of the exchange between politics and the media.

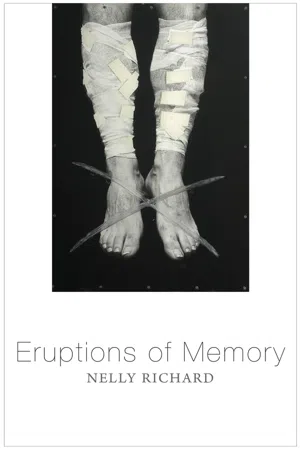

The Transition-era administrations followed a consensus-oriented script that turned memory into a solemn yet almost painless citation. Their evocation of memory failed to mention all the material injury of the past: its psychic density, its experiential volume, its affective trace, and its scarred backgrounds, the pain of which is diminished neither by the merely compulsory method of the judicial process nor by official memorial plaques. Public discourse during the Transition attempted to pay off its debts to the past formally without expressing too much regret, almost without reflecting at all on the repulsiveness, torture, hostility, and resentment that continue to rip apart living subjects. Like many words that are intended to circulate innocently – without weight or gravity – throughout the communicative pathways of media-saturated politics, the word “memory” seems to have erased from its public expression the intolerable, antisocial memory of the nightmare that tortured and persecuted subjects during the dictatorship.4 The word “memory,” thus recited by the mechanized speech of consensus, subjected the memory of the victims to yet another outrage, once again making them insignificant by allowing their names to be spoken in a language weakened through official routines that had previously guarded these identities from any investigations into the convulsions and fractures of history. Reduced to the meaningless language of objective certification, a few words testify only to the number of victims. The intolerable aspects of memory are not allowed to disrupt the expressive rules of the language used to refer to it. The consensus-oriented method of the “democracy of agreements” prohibited any eruption of voices that could reveal the paroxysms of rage and desperation felt by the victims’ families.

Biographical ruptures, narrative disarticulations

The experience of the post-dictatorship binds the social body’s individual and collective memories to figures of absence, loss, suppression, and disappearance. These figures are surrounded by the shadows of a suspended, unfinished, and tense mourning that leaves the subject and the object in a state of sorrow and uncertainty, ceaselessly wandering around that which is inaccessible in the body, as well as around the truth that both the subject and the object lack (it is absent) and need (they miss it).

In the most brutally sacrificial dimension of violence, the bodies of the missing are evoked by absence, loss, suppression, and disappearance. They also connote the symbolic death of a social historicity whose mobilizing force is no longer recoverable in its utopian form. This force of historicity survived during the dictatorship as a struggle over meanings, as a struggle to defend an imperative and urgent meaning in combat against the military regime. The conditions of existence had to be reinvented in order to survive the catastrophe of the dictatorship. Undoubtedly, the epic task of confronting everything as a matter of life and death, every act as dangerous, entailed increasing the rigor applied to practices and identities. Such overexertion ultimately resulted in exhaustion. Today, many are tired of the heroic discipline and combatant-centered maximalism that once demanded their fidelity, now preferring instead to content themselves with small, neo-individualist, personal, everyday satisfactions. Such partial tactics of isolation and distraction create the illusion of certain “relative autonomies in relation to the structures of the system” when it is no longer reasonable to believe in the imminent demise of this system.5

However, the democratic transition and its normalizing networks of order also deactivated the exceptional character of the quest for meaning as it was presented to us at the moment of struggle against horror and terror in zones of life and thought in a state of emergency. Extremism had been expressed previously through the defense of irreplaceable (absolute) truths. During the Transition, it became part of the regime of the flat substitutability of signs with which (in the name of evaluative relativism) neoliberal society de-emphasized the desire and passion for change.6 Whatever the painful motive for this renunciation may be, the post-dictatorial condition is expressed as the “loss of an object” in a situation marked by “mourning”:7 psychical blockages, libidinal withdrawals, affective paralyses, inhibitions of will and desire in the face of the sense of having lost something unrecoverable (body, truth, ideology, representation). Post-dictatorship thought, as Alberto Moreiras argues, is “more suffering than celebratory” because, “like the mourning that must fundamentally both assimilate and expel, thought attempts to assimilate the past, seeking to reconstitute itself, reform itself, following lines of identity with its own past; but it also tries to expel its dead body, to eliminate its tortured corruption.”8 This melancholic dilemma between “assimilation” (remembering) and “expulsion” (forgetting) marked the post-dictatorial horizon with narratives split between silence (the lack of speech connected to the stupor resulting from a series of unassimilable changes to the subject’s continuity of experience due to the velocity and magnitude of these changes) and overexcitation (compulsive gestures that use artificially exaggerated rhythms and signals to combat the tendency toward depression). At one extreme we find biographies imprisoned by the sadness of an unmovable memory in its morbid fixity, and, at the other extreme, light stories that emerge hysterically through the over-agitation of the quick and the fleeting in order to achieve trivial media recognition. From silence to over-excitation; from bewildered suffering to the spoken simulation of a supposedly recovered normality: these responses to tragic memory reveal, consciously or unconsciously, the problematic status of historical memory in the post-dictatorship era. It is a memory that must avoid both the nostalgic petrification of yesterday in the repetition of the s...