Lecture of 12 January 2000

- Doubts and reflexivity.

- Birth of the artistic field.

- A commentary on Mallarmé’s text on Manet.

- A critique of criticism.

- The Zola–Manet–Mallarmé paradigm.

- The inconsistencies of Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

- Mallarmé on Manet.

- The structural homology between the artistic and religious fields.

- Belief and the return to the sources.

Doubts and reflexivity

I shall start with a sort of confession or disclosure. Deep down, I find myself wondering how I ended up in the situation I find myself in now, having to lecture on something just as I have started radically doubting that I – or anyone else, for that matter – can speak on this subject. It may sound rather odd to hear me say this, but the more I know about both Manet’s work and what is usually called its ‘context’ – that is, its social history, the history of its artistic field, etc. – the more difficult it seems to me to make a novel and necessary contribution to the topic that I rather recklessly chose to focus on in these lectures.

This being said, now that I have started on this course, I am going to forge ahead. This prelude was no rhetorical gambit, however: it is what makes it possible for me to carry on at a time when I am riddled with doubts about the legitimacy of what I am about to say. I shall briefly remind you how I came to work on Manet. Last year, after a set of preliminary reflections on the possibility of a critical social history of art, I started to formulate some thoughts towards an approach to works of art based on their social reception, considered as a methodological tool for their analysis. I do not take the social reception of art works at face value: in other words, I do not take the critical texts themselves as the principle for my interpretation of the critics. Instead, I take the texts that the critics bequeathed us and submit them to a critical analysis, which then becomes the instrument for my interpretation of the works of art. This sort of preliminary reflexivity – I argued that critical discourses could only be used on this condition – may at the same time be self-destructive. It may be at the origin of the niggling doubts that I expressed at the start of this lecture.

Birth of the artistic field

In fact, I thought that by doing what I usually do – i.e., analysing the space of the different positions that a work has given rise to, relative to the space occupied by those who took these positions – I would be able to avoid being trapped in a circular logic and find a sort of stable point from which to work. I tried to describe the academic institution: I spoke of the way it operated, what its logic was, how the masters – I called them the ‘masters’ as opposed to the ‘artists’, who invented themselves by opposing them – were recruited and how they were trained and trained their students, how the studios operated, and what a studio culture was. I also told you of the many analogies of this culture with the culture of the classes préparatoires, and reminded you that these analogies needed to be examined. And I tried to show you that the true principle of the academic aesthetic lay in the logic governing the operation of the academic institution, which I called the ‘academic eye’.

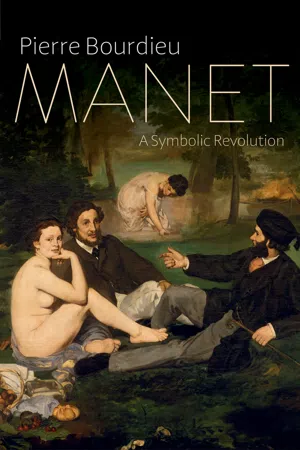

The academic eye has a certain coherence, there is a logic to it. And since the quest for coherence is the task of the anthropologist, I tried to find the coherence of this eye, of the gaze which is expressed in pompier painting. I found this coherence in the academic institution, while nevertheless bearing in mind that it was riven with contradictions and conflicts: the danger, with any attempt at interpretation, is to overemphasize coherence, whereas institutions are often riven with contradictions and internal conflicts. For example, Thomas Couture, Manet’s master, was himself not so much an anti-academic as an academic painter, even if he occupied a marginal position relative to the academic institution. Then, I briefly described the set of factors which, it seems to me, can explain the transformations of the academic institution, in particular the passage from the academic nomos to the anomie that followed the revolution operated by Manet and symbolized by Luncheon on the Grass [1].1 I shall return to this in due course.

To examine the passage from nomos to anomie is in fact a different way of describing the birth of an artistic field, that is, of a space where the very idea of art is under question. The definition of art no longer goes without saying, there is no central body which decides what qualifies as art (‘This is a painting’), the question of what is a painting and who has a right to say what a painting is has become a moot point. This challenges at once the status of the artist, the status of the critic and, more generally, the status of all the characters involved in the field of art (including art dealers, salesmen, and so on). The facts that I have established here are proven, and although perhaps not very novel, I think they explain why Manet aroused such historically unprecedented levels of fury. He radically questioned the universe into which he entered and performed a series of actions which changed everything, or which at the very least forced everyone to change everything. As I have already said, something similar happened in the domain of the theatre in the case of the inventor of the ‘théâtre Antoine’, André Antoine, whose innovative approaches to staging suddenly unleashed a series of questions which have not all found an answer yet.

This was roughly what I intended to say last year. I cannot remember what analytical approach I took: there is a whole set of factors – morphological factors, as Durkheim’s followers used to call them – such as an increase in the number of painters. There are some very fine works on the history of the Impressionist movement, which I did not quote in French, such as those of the Whites (he is a sociologist and she is an art historian):2 their study is based on very rigorous statistics. It is an exemplary work. I described the processes which transformed the social foundations of the artistic universe, and I gave you a fairly precise account of the system of explanatory factors, which, it seems to me, was capable of achieving this global change. One of these explanatory factors was of course Manet himself, who was so to speak the Heresiarch, the founder of the heretical sect, which managed to achieve this very profound transformation by taking advantage of all the opportunities presented by the historical and social changes that I told you about.

A commentary on Mallarmé’s text on Manet

This is more or less what I told you about in a nutshell, give or take a few oversimplifications. I shall stop here. I do not think that I can take this much further. Today, in order to ease you gently back into my argument, I shall resume my commentary of the very fine text that Mallarmé wrote on Manet in 1875, that is, around the time when Manet’s career had reached its midpoint. This text has a rather strange history. I shall try to describe the context in which we should situate it.3 All things considered, the story I am going to tell you today has three protagonists: there is Manet, who is the focus of Mallarmé’s analysis, there is Mallarmé himself, and then there is a third character, Zola – there is even a fourth, Baudelaire, but he is only mentioned in passing. It seems to me that we must take a global approach to this trio, because they mapped out fairly clearly the space of the questions that we may ask about Manet, or, to be more precise, the space of the questions that Manet’s life and works have given rise to.

I shall briefly remind you of some of the characteristics of our cast, as though this were a play. Manet was from the Parisian bourgeoisie, or even haute bourgeoisie: his father was a senior official in the ministry of justice and his mother came from a family of diplomats. He had been a student at the Collège Rollin, alongside Antonin Proust, who would later become one of his biographers and commentators. He attended the École navale and then went off to sea, before putting an end to what would have probably become a career in the navy – this was the career path that had been marked out for him. He then turned to art and headed for the studio run by Thomas Couture.

In his Self-Portrait with Palette (1879), Manet looks similar to the engravings we have of him: although he has a beard, which places him in the bohemian category, it is very finely trimmed and well kept. All those who met him in his studio at the time emphasized that there was something bourgeois, or even dandy, about his looks. What is paradoxical is that this dandy was a revolutionary. Indeed, very early on, his defenders started invoking his bourgeois character to counter the attacks of those who saw him as something of an ignorant and unschooled barbarian: the fact that he had gone to the best schools was exploited – as it were, a priori, through a sort of authoritative argument – to discredit any notion that he might have unwittingly blundered. This gives you a sense of his solidly bourgeois habitus.

Mallarmé was ten years younger than Manet. He was from the provinces but had moved to Paris at a very early stage in his life. His father was a civil servant, but was not as high-ranking as Manet’s father: he was a deputy head clerk and then a head clerk in the tax office (administration de l’Enregistrement), which was not as high flying as Manet’s family. Mallarmé had been a mediocre student, thus disappointing his family, as had Manet before him. He obtained a certificate which allowed him to teach English and became a teacher in various provincial lycées before moving back to Paris in 1871, where he taught until he was granted leave of absence, shortly before reaching retirement age.

These very basic but relatively significant properties meant that these two figures had much in common. In particular, they both came from the higher end of the social spectrum but their social standing was in relative decline, in so far as artistic and literary careers were not highly regarded by the bourgeoisie, especially when they were marginal. If only they had taken the royal highway opened up by an academic career, this might have afforded some consolation to their bourgeois families. Instead, they opted for marginal byways.

Manet painted a portrait of Mallarmé (in 1876) [19] and of Zola (in 1868) [21]. It is interesting to juxtapose these two portraits, and place them side by side. Manet had very different relationships with the two men. I think he liked Mallarmé more than he did Zola, which was an effect of the affinities between their habitus. The people we like are often people with a similar, or at least homologous, habitus to our own. They enjoyed each other’s company and often spent whole afternoons together. Mallarmé visited Manet in his studio virtually every day until the painter’s death. They lived in almost the same neighbourhood, and this was not by chance either, the Parisian space being a socially structured space: living on the right bank is significantly different from living on the left bank, and they both lived on the right bank.4 It is not by chance that Mallarmé passed Manet’s studio on his way to school and stopped there for a chat and enjoyed spending time there. Indeed, it seems likely that Manet painted his portrait of Mallarmé in his studio. Mallarmé is depicted striking a very informal pose; he is leaning back slightly, resting onto his right elbow; there is a cigar in his right hand, which indicates a relaxed, casual mood. He does not look straight at us, he does not challen...