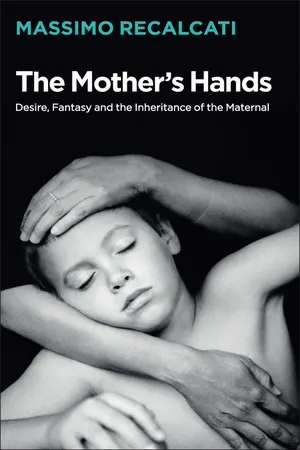

The Hands

I have a distant yet persistent memory. At times I ask myself why it is still with me after all these years, why it has not entered, as is the case with so many others, that limbo of memory without memory that is a part of our daily lives.

I was nine years old. My mother and I were in our old house at Cernusco sul Naviglio on the eastern outskirts of Milan, situated at the back of the flower shop belonging to my father and his brothers. We were in the little dining room watching a film, on our black-and-white television, which was based on a real-life story: for hours on end a mother holds in her own hands the hands of her child who, playing on the terrace on the top floor of a large block of flats, had found himself clinging to the balcony railings for dear life. This is the memory that has stayed with me all these years: a mother holds in her own hands the hands of her child who is suspended over the void.

Writing this book pushed me to watch that film again, not least to reassure myself as to the reliability of my memory. Had I imagined it? Had I kept within me a non-existent memory, or, as psychoanalysis describes it, a ‘screen memory’? Our research reassures me: the film really does exist in the mysterious archives of the RAI (the Italian National Broadcaster), and is in fact called La madre di Torino [The Mother of Turin]; the director is Gianni Bongioanni; the year of production, 1968.

Watching it again I cannot help but notice the repositioning carried out by my memory. The scene takes place in Turin on Corso Peschiera, on the corner of Corso Francia, in a building in a residential area (why, in my memory, was it a building in a run-down council estate?); the mother was a beautiful, elegant woman (why had I remembered her as so old?). The plot is essentially as I remembered it: a child of four or five years old, so pre-school (why do I remember him walking uncertainly, as if he were younger than two?) who, whilst playing at shooting an aeroplane in the sky, falls into the void from the top floor of the great palazzo, ending up dangling miraculously from the bars of the railing. The mother, who notices his absence, immediately helps him, gripping him firmly in her hands.

Her attempts to attract the attention of passers-by are in vain. The noise of the cars and daily street life carrying on, indifferent, masks the mother’s screams, whilst time passes and the woman’s hands, now weakened by the prolonged effort, seem to have to let go those of her child.

The pair appear isolated from the rest of the world; one attached to the other, without hope (why do I remember the real desperation of the child and the mother, even though the acting is so flat, void of any authenticity, to the point that, watching it again, it appears almost farcical?). Then a barman casually looks up, his gaze meeting the child’s body swinging in the void, and alerts the passers-by and firemen. I had also correctly remembered the happy ending: mother and child are saved by the brave gesture of a worker from a nearby garage, who anticipates the firemen’s arrival and renders futile the local people’s awkward attempts to help. This is the moment (which I also recalled perfectly) in which the mother slowly collapses to the floor holding those hands in her hands, now rigid from the strain. How much time had passed? An entire day? How long had that mother held her son’s life in her hands? (Why in my memory was it a period of time that was unending?)

The initial question is still valid: what justified the obstinate permanence of such a recollection in my memory, along with all of its distortions? Did the (relative) proximity of my age to that of the child, along with his frivolousness, favour a projective identification? Did I perhaps feel like a child suspended over the void who would have liked to be taken by his mother’s hands? Did the mother–child pairing in the film intensify that of me and my mother as we watched the film? More radically, today I can see how, in that scene, the mother is a presence capable of alleviating anxiety, to extricate that life from the state of absolute abandonment into which it is launched.

Why have I never forgotten the mother of Turin? I try to answer that question by first thinking of how I have often felt as though I was suspended over the void just like that child, and how many times I have called from the loneliness of that void for the hands of those I loved to support me. Is this not perhaps the most radical condition of human life? Does life not come to life through the continual reaching out, holding on to and entrusting ourselves to the hands of the Other? Is mother perhaps the name that defines the hands of this first Other, which each of us has invoked in the silence of our own void? Is being born not always being taken by the hands of the Other? Is this not what led Freud to identify in the first face of the mother the figure of the ‘extraneous help’1 or ‘saviour’?

The mother of Turin was a news item destined to be forgotten along with so many others. What were that mother and son called? I cannot remember, not even now after having recently watched the film, but I doubt they even had names. They were just a mother and a son. It was just a nameless son holding on to the hands of a nameless mother. This is also the case with the father and the son in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road: they are also deprived of their own names. They are just hands that hold on to other hands, hands held tight in other hands and all around is the void, the nothing, the non-sense, the body of a child that swings over the abyss, the body of a child who wants to be protected from the cold, dark night.

That’s it, I tell myself today, that which never passes, that which proved itself to be truly unforgettable for me, that which persists in these images: the hands of the mother of Turin clutching those of her son hanging over the abyss. It is a metaphor for the Other, who responds to the scream of life, refusing to let it fall into insignificance, instead offering the support without which it would plunge into the void. This is what the mother of Turin has impressed indelibly upon me and that I can see once more: the silent resistance, the offering of one’s own bare hands, the obstinate refusal to leave life alone and without hope, the gift of a presence that does not disappear. This is the ‘plant’ of the mother that captures, in Rilke’s words, the ‘dew’ and the coming of the day.

Are the hands not the first face of the mother? Have they not been the hands of my mother, which caressed my body, sowing letters, memories, signs, ploughing it as if it were earth? How important can a mother’s hands be to a child? This is another reason that image of motherhood has never left me, has proved indelible.

In the Freudian description of the maternal Other as the first ‘saviour’ at that traumatic onset of life we can find an initial definition of the mother as ‘the closest’ Other, who knows how to respond to the call of life that is screaming out. If, as Freud and Lacan believed, human life comes to life in a condition of ‘prematuration’, ‘lack of preparation’, ‘fragmentation’, ‘defencelessness’, ‘absolute abandon’, in a condition of inadequacy, vulnerability, of being exposed to the non-sense of the real, the hands of the Other (the presence of the Other) are required before all else to safeguard that life, protect it, remove it from any danger of falling.

The hands of the mother of Turin are not hands that punish, castigate or humiliate; they are not hands of anger or violence; they are not hands that hit and that we can recognize in our childhood scars. They are bare hands, hands that are offered to other hands, hands that sustain the life hanging over the bottomless abyss. Life, human life, needs to find these hands, the bare hands of the mother, the hands that save it from the precipice of non-sense. Was this not what my childish gaze, sitting next to my mother, wished to project onto the black-and-white television screen? For me, this remains the first face of motherhood, destined to withstand the ravages of time and all the transformations of the family that are currently taking place.

If motherhood no longer coincides with the ability to generate life or the emotional experience of gestation but, thanks to the powers of science, has been extended to other possible forms that do not require coitus or the real of sex, the hands belonging to the mother of Turin remind us of an essential function of motherhood that no historic change will ever cancel out: the mother is the name of the Other who does not let life fall into the void, who holds life in their own hands, stopping it from falling; it is the name of the first ‘saviour’.

This is a nodal point in this book: that which I refer to here as ‘mother’ does not necessarily correspond to the real mother understood as the biological female parent of the child. Freud already considered ‘mother’ the name of the first figure of the Other that takes care of a human life which it recognizes as its own creation. This means that ‘mother’, like ‘father’, is a figure that transcends sex, blood, ancestry and biology.2 ‘Mother’ is the name of the Other who holds out their bare hands to the life that comes into the world, to the life that, upon entering the world, begs for meaning.

The Wait

Motherhood is a great figure of waiting. Here is another lesson that we can take from the mother of Turin: waiting, not allowing yourself to be overwhelmed by time, resisting, not being consumed by impatience.

If you listen to mothers (as a psychoanalyst often does), waiting occupies a central place in their discourse, particularly during pregnancy. Is it not a special wait, that of waiting for the child to grow and be brought into the world? But a mother’s wait is unlike any other. She is not waiting for something: a train or an anniversary, a concert or a contract. Motherhood is a radical experience of waiting because the person waiting has no control over what she is waiting for. The unknown runs through every real wait: we never know what or who we are waiting for, we never know what it will be like at the end. The wait upsets what is already known, what has already been learned, what has already been seen, suspending our ideal of mastery. A quota of uncertainty always cuts through the wait for the Other even when we believe we know it well: will it be the Other I know, that I think I know, that I have learned to recognize?

The mother’s is not a simple wait for an event that might happen in the world, but for something that, though she is carrying it with her, inside her, in her own belly, in her own womb, appears as a principle of otherness that makes an other world possible. The wait is an incredibly profound element of motherhood because it reveals that the child comes into the world as a boundless transcendence, one that is impossible to anticipate and destined to change the face of the world.

It also happens in love, when we wait, when we continue to wait for someone we miss, someone we love, despite knowing their body and their name so very well. Always in love, the person we love preserves a level of otherness that is impossible to overcome, and...