In the beginning is doubt.

Before every sentence, every word, there is this threshold: Is that right? How do you know it’s true? It is fair? Besides being true, is it also truthful?

And those are just the doubts about what I might say.

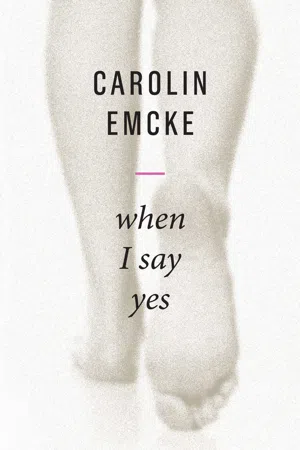

I write as if I were mumbling: softly, more to myself than aloud for others to hear. Thinking, rather, but with a keyboard. Writing makes thinking more precise. It’s intimate. Like whispering. Or like mumbling. Maybe that’s why I always write barefoot. As if, with my feet in shoes, I would only be able to think in conventions.

The moment I imagine an audience, everything dissolves, and immediately I am silenced. Objections step in front of my own ideas and upstage them. To say nothing of the antagonisms, the raging animosities. They scare me; they get under my skin, like poison; I can feel it spreading in my body, all over; feel it paralysing me – my voice, my will, my self.

In the beginning is always doubt.

Sometimes I wish I could turn it off. But, if I did, the I of my writing would not be me. It is in writing that I find myself, invent myself.

In my childhood, when there was no way to avoid mentioning the supposedly unmentionable, it was hinted at by a word in dialect. Mitschnacker was a word in Plattdeutsch, the Low German of the flat, northern country, and even children who didn’t know any Plattdeutsch sensed the word’s sinister connotation. ‘Don’t let any mitschnacker get you’: that’s what they said to us on our way out into the world – to school or to the sports field. It indicated the danger, but indirectly. As if the dialect could cushion what it was we had to be warned about. We were not to talk to anyone who tried any mitschnacken – that is, who tried to talk to us and gain our trust. But what would happen if a stranger did talk us into going with them – that was left unspoken.

And we left it unquestioned; we don’t question it even today.

What can happen, what did happen, time and again, what happened to generations of girls and women before us, what still happens to girls and women – not only, but mostly – all over the world, on the way to school, on the way to fetch water, on the way to the pasture, on the way home – what they can do to us: that is not stated. Our mothers and grandmothers before us were informed the same way: without the information. No one told us we could be manipulated, lied to, picked up, picked on, attacked, abducted, in a car, in the bushes, in the woods, in a shack, in a basement; no one said we might be raped, choked, injured and killed. And most certainly no one ever said the danger lay not only outside, among strangers, but also, and most often, close at hand, in our own homes, in our own families.

‘Don’t let any mitschnacker get you.’

That’s a farce. It sounds funny. As if it were merely about someone who talks too much. But what it means is not the talking; it’s the danger of violence after the talking.

It’s these rhetorical disguises that facilitate what they claim to prevent. Incredible: supposedly they’re warning you about something, but what it might be, they don’t say. It’s not just rose-tinting, because that would mean denying there was anything you had to be warned about. It’s leaving unspoken what someone might do to you. As if it were indecent to talk about it – suppressing all mention of it instead of suppressing the act itself.

Thus there is a taboo, not against the criminal act, but against naming it. Right from the start. Thus the convention undermines not the person who perpetrates violence but the people who want to tell us about it. The suppression of speech shifts the onus of justification. It’s the person who wants to speak out about something unmentionable who feels wrong or dirty. That is where the complicity lies.

In order to criticize something, you have to be able, and willing, to imagine it. In order to imagine something, you have to be able to name it. If violence is kept abstract, if there are no concrete words for it or descriptions of it, that keeps it unimaginable, implausible, untouchable.

The bathrobe.

I just can’t get over the bathrobe.

Everywhere in the #MeToo stories, this bathrobe keeps turning up …

Not at the beach on holiday. Not in the bedroom at home. But at a meeting in the office. At a meeting in a hotel. In what purports to be a professional context.

What is this obsession with the bathrobe?

I don’t get it. I really don’t understand it. I simply don’t understand the scene. What’s happening in it. What the point of it is. No one ever explains it. Not in the situation itself, and certainly not after the fact. You have to think it all through yourself. Young women, older women, co-workers, employees, hotel staff, interns; women these men have been working with for some time, or complete strangers; women who expect to see a man in a suit, in jeans, in whatever clothes, but in any case dressed – women are called in, and then:

ta-daaaaah,

the bathrobe scene.

I picture this in my mind’s eye all the time. The only bathrobes I can imagine are white terry cloth. I have no idea why. And yet guys like that probably wear silk … what do I know? I’ve been hearing these stories so long, it’s interfering with my relationship to my own bathrobe.

Answering the door in a bathrobe – what’s that about? Is it the prologue to an anticipated conquest? Is it an invitation to sex? Is it pride? Look what a fabulous dick I have? Do they honestly believe that? A woman goes to a meeting and, before she knows it, out of the blue, a dick walks up to her? That could be the opening of a joke. Like the psychiatrist jokes people used to tell: ‘So this patient comes in dragging a toothbrush on a string.’ Only this joke starts differently:

‘A dick walks into the office wearing a bathrobe …’

Is that supposed to afford pleasure? And, if so, to whom? What kind of pleasure does it give the dick’s owner? Pleasure in humiliation? He’s not exhibiting his naked body, he’s parading his ability to control: his ability to suspend all propriety (in a work context), his ability to dominate, to humiliate, at a whim, whenever he feels like it. If it’s not appropriate to the situation, so much the better; if it goes against all convention, against what’s customary in a meeting, against what ordinarily makes up desire: mutual pleasure and tenderness, passion and devotion to another.

The bathrobe is always out of place.

So far, there is not one story in which the bathrobe turns up in a way that is harmless or appropriate or seductive. No story in which a couple want to throw something on after a night of passion, no story in which a man wants to arouse a woman, one woman wants to arouse another, a woman wants to arouse a man by letting themselves be looked at, revealing themselves, surrendering themselves to the gaze of another, with a bathrobe on at first, then without. No story in which the bathrobe conceals something that is then revealed slowly, the wearer’s nakedness, the wearer’s vulnerable physicality.

The bathrobe is always out of place.

Clashes with the context. The situation. Is neither erotic nor practical nor pretty.

And yet we often hear: ‘Well, what did she expect? Goes to a meeting in a hotel room – how naive can you get?’

In a work context, a man asks a subordinate or dependent woman to meet him. It may be in an office or in some other place. In industries where work is mobile, where people have to travel to different cities to meet with co-workers and contractors, it very often may be a hotel room that has been booked for appointments and meetings. A man asks a woman to meet him there, a woman who knows she is less protected because she’s less senior, less known, less connected, less visible, less audible; because she’s a woman; perhaps unsure because she has never been alone with a revered or even just a famous professor, a priest, a producer, because as the housekeeper she’s responsible for the cleanliness of the hotel room or the offices, because as the nurse she’s responsible for the patient, because as a police officer or a soldier she’s subordinate to a superior,

because she’s wearing a headscarf,

because, because, because, …

because she doesn’t know what to expect.

After all, how is a person supposed to expect that?

Is it naive to expect not to be humiliated?

Is it wrong to expect not to be harassed, attacked, injured, choked? Is it naive not to expect to have your head beaten against the wall, not to expect to be dragged across the floor by your hair, pulled into the bathroom, penetrated by force; is it wrong not to expect to be pissed on and tormented? Is it really so naive to expect not to be raped?

What kind of logic is that? What kind of concept of humanity? What kind of concept of men? As a woman, must I accept that it’s unrealistic not to be seen and treated as an object, as a thing, as an available, usable body?

What kind of idea is that: that people should go through life anticipating every moment that they are going to be another person’s object? How should parents teach that to their children? How have generations of mothers (or fathers) taught it? What a responsibility: all parents would like their children to go through life without fear, to feel safe and free, but at the same time they don’t want their daughters (or sons) to grow up naive about what others see in them or what others want to do to them. Generations have grown up with this indistinct knowledge of their own vulnerability – and we carry that with us through life.

When I had been with my first employer for just a few weeks, I received a call on the office phone from the publisher. That was unusual. He was rarely seen in the editorial offices. But he did have a word to say from time to time, and occasionally he turned up in person. Timidly, I took the receiver, expecting to be criticized or corrected. Instead, there was a jolly gentleman on the line full of praise for a story I had written. After I rang off, I turned around, and half the department was standing in the doorway of my office, waiting to hear what he had wanted. Before I could explain, my editor said, ‘If he’s asked you to meet him at home, I’m going with you. You’re not going there alone.’

I hadn’t been asked to meet him at his home. But the stories of young staff writers who had been summoned to meet with the publisher, who then received them in his bathrobe, were notorious. How many women had had to go there alone before my time, I don’t know. Nor do I know what happened. That was passed over in silence. What the silence concealed, I can only guess. But I do know that my editor was certain ...