How Everything Can Collapse

A Manual for our Times

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

How Everything Can Collapse

A Manual for our Times

About this book

What if our civilization were to collapse? Not many centuries into the future, but in our own lifetimes? Most people recognize that we face huge challenges today, from climate change and its potentially catastrophic consequences to a plethora of socio-political problems, but we find it hard to face up to the very real possibility that these crises could produce a collapse of our entire civilization. Yet we now have a great deal of evidence to suggest that we are up against growing systemic instabilities that pose a serious threat to the capacity of human populations to maintain themselves in a sustainable environment. In this important book, Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens confront these issues head-on. They examine the scientific evidence and show how its findings, often presented in a detached and abstract way, are connected to people's ordinary experiences – joining the dots, as it were, between the Anthropocene and our everyday lives. In so doing they provide a valuable guide that will help everyone make sense of the new and potentially catastrophic situation in which we now find ourselves. Today, utopia has changed sides: it is the utopians who believe that everything can continue as before, while realists put their energy into making a transition and building local resilience. Collapse is the horizon of our generation. But collapse is not the end – it's the beginning of our future. We will reinvent new ways of living in the world and being attentive to ourselves, to other human beings and to all our fellow creatures.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

The Harbingers of Collapse

1

The Accelerating Vehicle

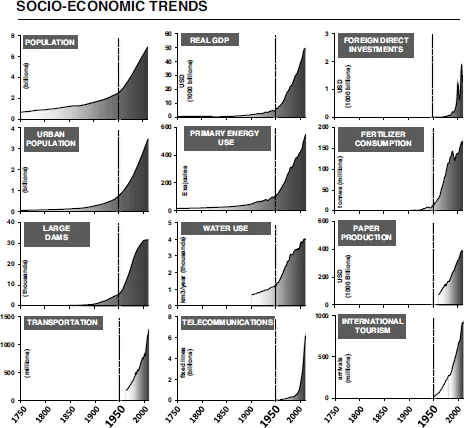

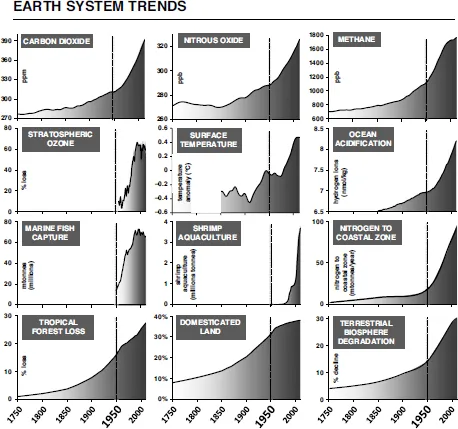

A world of exponentials

Total acceleration

A century has elapsed since the invention of the steam-engine, and we are only just beginning to feel the depths of the shock it gave us. But the revolution it has effected in industry has nevertheless upset human relations altogether. New ideas are arising, new feelings are on the way to flower. In thousands of years, when, seen from the distance, only the broad lines of the present age will still be visible, our wars and our revolutions will count for little, even supposing they are remembered at all; but the steam-engine, and the procession of inventions of every kind that accompanied it, will perhaps be spoken of as we speak of the bronze or of the chipped stone of prehistoric times: it will serve to define an age.8

Table of contents

- Cover

- Front Matter

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: We’ll Definitely Need to Tackle the Subject One of These Days . . .

- Part I The Harbingers of Collapse

- Part II So, When’s It Going to Happen:?

- Part III Collapsology

- Conclusion: Hunger is Only the Beginning

- ‘For the Children’

- Postscript

- Notes

- End User License Agreement