![]()

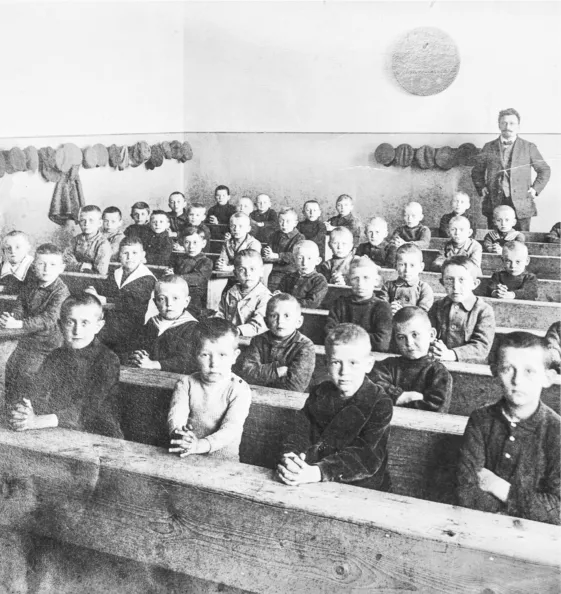

The third educational revolution introduced the factory model where massed ranks of students sat in front of a teacher/lecturer at the front of the room, all learning at the same pace and all trying to rote-learn the same answers in the same way.

Chapter One

The Four Revolutions in Education

The history of education is the history of humanity. Only three education revolutions can be said to have occurred during the last three to five million years.1 We are in the early morning of the fourth education revolution, with misty patches and hazy outlines, some tantalising glimpses of what may lie ahead, but without a clear path yet defined. This coming revolution is underpinned by the collection, analysis and visualisation of very large data sets, harnessing Artificial Intelligence (AI) and immersive technologies such as Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) to help us make sense of it all.

We have heard much since the World Economic Forum in January 2016 about the so-called ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’. We still need to wake up to the Fourth Education Revolution. Now is a good time.

Schools and universities today would be recognised by our forebears in the year 1600. Why do we say this? The teacher or lecturer today remains the dominant presence: they are an authority (i.e. a master of their subject) and in authority (i.e. they command the learning environment). They typically stand at the front of the learning space; students are organised into groups by age; class size typically varies between 20 and 50; the day is divided into the teaching of different ‘subjects’; students study in libraries stocked full of books and audiovisual resources; teachers and lecturers prepare students for, oversee and mark regular tests and periodic exams; and these result in students passing with various grades or categories, or failing a subject/course/degree.

Most of this will be swept away by the fourth education revolution. Barely a single facet of this education model will remain unchanged.

The First Education Revolution: Organised Learning; Necessary Education

The beginnings of ‘learning from others’, in family units, groups and tribes, constitute the first education revolution. This can also be said to constitute the origins of mankind. This development did not take place in one precise place on earth, nor at a precise time; it took place over hundreds of thousands of years and in diverse places. We can however highlight key moments. Dating back some 2.5 million years, some of the earliest stone tools to have been used have been discovered in Ethiopia, which suggests that learning was being handed down from generation to generation, with knowledge about how to use the tools to cut open animal flesh and grind bones passed down from parent to child. Hominids (i.e. great apes, including human antecedents) began transferring knowledge systematically about how to hunt, how to build seasonal camps, how to use fire, and how to migrate over long distances.

Daily life during the period of the first education revolution revolved around mere survival and bringing up the next generation; it left little time for leisure, the arts or for conjecture. Pleasure came from bodily experience. Life was harsh and itinerant, and changed little for a very long time. Homo erectus, a species of human antecedent, began to colonise areas in sub-Saharan Africa some 1.8 million years ago, migrating approximately 1 million years ago into North Africa and the Near East, reaching northern Europe 500,000 years later.

Homo sapiens (‘wise human being’) did not emerge in Africa until approximately 200,000 years ago. Their cerebrum had evolved to roughly its present size and their vocal apparatus gradually modified to enhance the development of language. Some 100,000 years ago, Homo sapiens started a migration northward out of Africa, reaching Australia 50,000 years ago, and the Americas some 35,000 years later. Homo sapiens co-existed for a time alongside Homo erectus in eastern Asia and with Neanderthals in West Asia and Europe. But the more sophisticated social understanding and adaptability of Homo sapiens allowed them to triumph and to spread more successfully than other early hominids: Homo erectus died out approximately 140,000 years ago, while Neanderthals remained until some 40,000 years before the present day. Both types left behind large numbers of stone tools, showing us that the knowledge of how to use them had been successfully transmitted down the generations.

By the end of this first phase of education, Homo sapiens might have triumphed. But life still consisted of bands of hunter-gatherers eking out life, with daily existence differing little from their predecessors at the very beginning of the first education revolution.

The Second Education Revolution: Institutionalised Education

This second phase, institutionalised education, was ushered in following the end of the last Ice Age in 10,000 BC. Now we see the origins of settled life, with developments in the stable production of food and urbanisation. Improvements to agriculture made possible a growth in human population between 8,000 and 4,000 BC, encouraging human beings to work together cooperatively. This new lifestyle allowed humans, for the first time in history, to live in settled places. Remarkably quickly, villages, followed by towns and cities, began to appear. Here is the start of civilisation.

Urbanisation began to occur in four diverse areas, roughly concurrently: in the valley of the Nile in Egypt; in the lower Tigris and Euphrates valley in Mesopotamia; along the Yellow River in China; and in the Indus valley in India. By 3,500 BC, cities had grown up in Mesopotamia, in Egypt by 3,200 BC, in India by 2,500 BC and in China some 500 years later. The emergence of writing was common to all four civilisations, along with political, commercial and legal systems to assist the administrative task of running more complex societies. Ruling classes emerged in all four, along with distinctive religious systems.

These new societies demanded a new range of specialisms, including learning about agriculture, trade, law, civic society, technology and religion. The sophistication of the emerging civilisation called for an altogether more systematic form of education than had been possible with the ad hoc transference of applied knowledge in the first education revolution phase.

Writing was essential to keep track of commerce, to record details of taxes and wages, and to record legal proceedings. It was widely required too in religion and in the recording of sacred texts, traditions and myths. It seems to have emerged first in Egypt and Mesopotamia towards the end of the fourth millennium BC. The Sumerians wrote their language, cuneiform, on clay tablets that were then dried and baked, whereas the Egyptians wrote on papyrus, made from overlaid and interwoven pith of the papyrus reed, which grew along the banks of the Nile. Each society evolved a representational form of language, including ‘phonetic’ forms of language. Sumerian, for example, was additive: each syllable had a meaning, and these could be combined to create new meanings. The symbols for ‘water’ and ‘head’ could thus be placed next to one another to represent ‘headwater’ or ‘origin’. The oldest known alphabet was developed in Egypt circa 2000 BC.2

Writing was a precise and sophisticated skill that required to be learnt. The need to teach it in a systematic and disciplined manner almost inevitably led to the development of institutional places of learning. The word ‘school’ has its origins in the Greek word skholē, meaning ‘leisure, philosophy, or lecture place’, and is the root of the word ‘scholastic’. The Greek for education, paideia, was synonymous with culture and civilisation. It suggested something that modern education systems have tended to forget: the development of the ‘whole’ person, physical as well as spiritual, and not just the mind or brain.

The first schools to teach writing had emerged by circa 2500 BC, known in Babylon in Mesopotamia as ‘tablet houses’. The strong association between state or religious organisations and school has been a common feature of education from the very earliest recorded schools in history. Many of the school tablets that have survived have been discovered in temples, and indicated important day-to-day business being transacted. Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum were both nominally places of worship, while religious schools were the only formal educational institutions in many areas.3

A tablet dating from circa 2000 BC provides an idea of life relating to Sumerian education. The student brought his lunch to school, where he would consume it under supervision. His teacher, known as the ‘school father’, would instruct the boy (no girls allowed) by rote repetition and by overseeing the copying out of ...