eBook - ePub

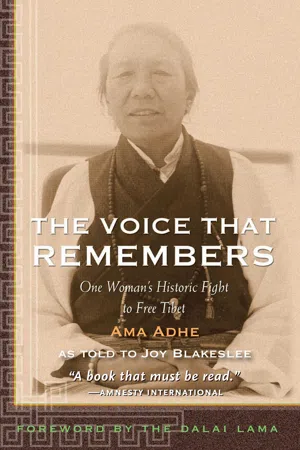

The Voice that Remembers

One Woman's Historic Fight to Free Tibet

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When Adhe Tapontsang--or Ama (Mother) Adhe, as she is affectionately known--left Tibet in 1987, she was allowed to do so on the condition that she remain silent about her twenty-seven years in Chinese prisons. Yet she made a promise to herself and to the many that did not survive: she would not let the truth about China's occupation go unheard or unchallenged. The Voice That Remembers is an engrossing firsthand account of Ama Adhe's mission and a record of a crucial time in modern Tibetan history. It will forever change how you think about Tibet, about China, and about our shared capacity for survival.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

BEFORE THE YEARS OF SORROW

Prologue

I have traveled a long distance from the land of my youth, from the dreams and innocence of childhood, and have come to see a world that many of my fellow Tibetans could never have dreamed of.

There was no choice but for me to make this journey. Somehow, I have survived, a witness to the voices of my dying compatriots, my family and friends. Those I once knew are gone, and I have given them my solemn promise that somehow their lives will not be wiped out, forgotten, and confused within a web of history that has been rewritten by those who find it useful to destroy the memory of many I have known and loved. Fulfilling this promise is the only purpose remaining in my life.

As a witness, I have prepared long and carefully. I do not understand the reason that this has come to be my part to play; but I understand very well the purpose of what must be said. Although the world is a bigger place than I had dreamed, it is not so large that all its inhabitants are not somehow connected. Sooner or later, actions make their way in a chain of effects from one person to another, from one country to another, until a circle is completed. I speak not only of the past that lives in me, but of the waves that spring from the rock thrown into the water, moving farther and farther until they reach the shore.

I am free now. There are no guards outside my door. There is enough to eat. Yet an exile can never forget the severed roots of beginnings, the precious fragments of the past carried always within the heart. My greatest desire is to return to the land of my birth. That will not be possible until Tibet is once again the land of her own people. At this time, I am considered an outlaw by the Chinese administration because I have chosen not to lower my head and try to forget the years of slavery that so many of my people have endured.

But I can remember back beyond the years of sorrow…looking outside the window of my present home in Dharamsala, I can see a mountain illumined by the evening moon. Though it is beautiful, it reminds me of another, greater mountain below which my early life unfolded.

I grew up in freedom and happiness. Now those memories seem to belong to another time, to a place far away. As I pass through the hours of each day, my heart remains with the memories of my family and friends whose bones have become part of a land now tread by strangers.

In 1987 the time came for me to leave my native land. In order to do this, it was necessary to convince the authorities that I would soon return and would speak to no one of my life’s experiences: of the destruction of so many lives through torture, starvation, and the degradation of slave-labor; of so many monasteries, the ancient treasures of which were desecrated and stolen for the value of the gold they contained; of the countless thousands of monks, nuns, and lamas who died in the labor camps; of my own family, most of whom perished as a direct result of the occupation of our land.

As I prepared for my journey they told me, “It is not good to die in a foreign land. One’s bones should rest in the land of one’s birth.” My heart agrees, and it saddens me to live with my people in a community of refugees. Yet, the heart of a culture lives in its people. Its preservation resides in their willingness and freedom to carry on its traditions. It is only in exile that I am free to speak of my life’s joys and sorrows. Until my land is free, it is in exile that I must remain.

Within my heart lies the memory of a land known as Kham, one of Tibet’s eastern regions. In voicing my experiences, I hope that the culture of my homeland as well as the horrendous suffering and destruction imposed on its people will not continue to be easily dismissed as a casualty of what has often been termed progress.

1

Childhood in the Land of Flowers

Even now as I close my eyes, I can recall my first memory—laughing, spinning, and falling in fields of flowers beneath an endless open sky. Playing among the flowers was our favorite summer pastime. My childhood friends and I would take off our boots and chase each other. Then we looked to see if a specific type of flower had gotten caught between our toes. To us this meant that we must run again through the part of the meadow where that flower grew. We loved to roll about on the hills, breathing deeply the fragrance of fresh earth and blossoms. We looked closely at the many different forms and colors of the flowers: so delicate, yet they had claimed this region as their own. In summer, such a vast variety of every color and shade inhabited the meadows that it was difficult for us to identify them all. In fact, our land was known as Metog Yul, or Land of Flowers.

The Tibetans in our region of Kham were nomads and seminomadic farmers. In summer, most farming families like mine took their herds to graze in the mountains. When this season arrived, the people of my village and various family members from outlying areas packed all our necessary belongings on yaks and mules, and journeyed to the nomadic mountain regions to graze our animals. There, we would stay from late June to October, camping in the grasslands and high alpine meadows of the Kawalori Massif.

Sometimes we children asked our parents to provide us with utensils, tea, and food, which we took to wherever we were playing and used to prepare our own refreshments. First we collected dry wood and built a fire, and then we made the tea. As it began boiling, we felt as if we had really accomplished something. I always remember the food we children shared together in the meadows as being more delicious than what we ate at home with our parents and elders.

My friends and I discussed things we had overheard from our parents’ conversations. We recalled pilgrimages our families had taken with us, describing to each other the various sights we’d seen on the way. Another favorite topic was the apparel and jewelry of our older sisters. All of us eagerly awaited the day when we could wear our own jewelry of silver, gold, and semiprecious stones. At mealtime our parents called us, but we pretended not to hear and continued playing, teasing each other, and sharing our dreams.

My father often sat with his friends discussing their various interests and enjoying chang, a popular barley ale. In the late afternoons, having grown tired of play, I loved to sit at his feet. He often gazed in the direction of the Kawalori peaks. Just the sight of those mountains often inspired him to raise his cup in a toast and sing:

Upon the snowy peaks the lion cub is born.

O mountain treat gently that which is your own.

May the white mountain be mantled always with eternal snow,

And may the mane of the snow lion grow long.

I would listen to my father and ask him to sing those words again and again. He explained to me that Kawalori, or “Eternal Snow,” is the name of a great Himalayan deity who resides within the mountains, and that the land on which we stood was his domain. Memories of my father have become intertwined with the recollection of that mountain’s snowy peaks. He taught me to love them as he did, illumined as they were with ever-changing sunlight, or silhouetted by the moon, surrounded by clean, ice-laden winter winds and the swirling mists of autumn and spring.

We had many friends among the region’s nomads, who were known to us as drogpa. They were a simple and very hardy people, suspicious of strangers, but true friends once their confidence was won. The nomads were very independent, preferring the open grasslands to the protection and confinement of towns. They were comfortable in even the harshest weather, residing their entire lives in large tents woven of yak hair. At seasonal intervals the nomads packed up their sturdy tents and moved their herds to new pastures. They relied almost solely on their herds for sustenance, for they did not farm and never saw the value of eating vegetables. They felt the growing of “such grass” for human consumption to be a foolish waste of time, and they found it humorous that people would give up the freedom of the open spaces to grow something that should rightly be eaten by yaks.

The only time the nomads came down from the mountains was when they wanted to trade, to pay yearly taxes in animal products, or for the purpose of pilgrimage. The tribes had their own hereditary chieftains and lived according to their own tribal laws. Though they spoke a dialect somewhat different than our own, we could understand each other.

During our summer stay in the nomads’ region, we camped in comfortable yak-hair tents like theirs. It was a very peaceful time. Aside from tending the herds, there were not many responsibilities, and we spent the season enjoying the company of family and friends. During the summer the whole mountain was full of animals—cattle, horses, sheep, and goats of the camping families. We also had 25 horses and a herd of about 150 cattle, an average size in Kham. We kept mostly dri, or female yaks, from which we obtained milk and the fine butter used both for cooking and as fuel for our lamps. Dri butter was so important to our culture that it was considered a proper offering in the temples and was used as an exchange in trade or even as payment in taxes.

Toward the end of October it was time to pack our tents and make our way down into the valley. My friends and I would sit one last time among the dry and fading wildflowers, looking around at the great open expanse. Some of us would not meet until the next summer, and so the parting was difficult, but we assured each other that when the snows melted, undoubtedly we would be together again.

During winter all the family members congregated in the kitchen, enjoying the light and warmth of the hearth’s fire and the security of each other’s company while gales swept and whistled around the house. In moments of silence after evening had fallen, the howling of wolves could be heard. In those months, we ate all our meals together. Before eating we prayed to Dolma, the protectoress and female Buddha also known as Tara.

During meals, we sat on low, carpet-covered beds, with a low table between us. Our parents were at the head of the table, and we children sat in order of our respective ages. Our servants ate with us, as did any travelers who happened to be passing by. Travelers were always welcomed in our village. In a land without newspapers, those passing through from other places were a valued source of information and entertainment. The head of the household went outside to meet the travelers, supply hay for their horses, and invite them into the house, where they were immediately offered chang or tea and asked about the nature and length of their journey. After the evening meal our family, servants, and guests sat and talked or listened to stories while drinking endless cups of butter tea, a requisite beverage in Tibet.

During these times, our elders also spoke of their youth, transmitting to us their remembrances of the situation in Tibet in those days. In that way, though we did not attend schools, we learned something about the history of our land and our religious heritage. Sometimes my parents and my older brothers discussed the hardships that they had endured during the Manchu and Guomindang incursions into Tibet. Sometimes there were recollections of old feuds that had led to sorrow in the days the family lived in the province of Nyarong.

We also heard stories about the Holy City of Lhasa in the province of U-Tsang, or central Tibet, where the Dalai Lama reigned. He resided in the Potala, “the high heavenly realm,” a palace of one thousand rooms and ten thousand altars situated on a hill rising above the city. They told us how the city, the most important center of pilgrimage in Tibet, held three of our greatest monasteries and the Jokhang shrine, where the sacred image of the ancient Buddha Shakyamuni was the site of many miracles. To visit Lhasa at least once was everyone’s heartfelt dream, and to hear it described in the evening firelight made us wonder when we would be able to make our life’s greatest pilgrimage.

My brothers loved to discuss their favorite subjects: trade, politics, and horses. Every Khampa, as we call the inhabitants of Kham, our region of eastern Tibet, learned to ride, and ride well, from a very young age. My father and brothers considered themselves experts in recognizing the necessary qualities of a fine animal. They sometimes mentioned a beautiful horse they had seen and how they wanted to buy it at any cost. Some women indignantly felt that men found their horses to be as dear as their wives.

The men sometimes recounted their rare travels to the trading centers of Amdo, the region of Tibet bordering Kham to the north, and their more frequent journeys to the important town of Dartsedo, close to the traditional Chinese frontier to the east. When they visited Dartsedo, my brothers saw lamas and traders from as far away as Lhasa walking through the streets. Great caravans of yaks carrying raw wool, precious musk, minerals, and medicinal items from Tibet ended their journeys in its caravanserais. In Dartsedo, the people of our region purchased tea, silk and brocades, needles, matches, and many other small articles. Sometimes even flashlights, pens, and other items were available from the United States, a modern country we knew little about, but about which we had great curiosity.

The activities of the Chinese in Dartsedo were a constant source of interest to my elders. Living as we did in the Tibetan borderlands close to China, the Khampa leaders were always watchful of our Chinese neighbors’ actions. Our province of Kham bordered China’s western province of Sichuan, and for two centuries there had been disputes regarding this easternmost territory of Tibet.

Dartsedo had once been the capital of the native Tibetan state of Chagla. In the late nineteenth century, the frontier state of Chagla had firmly allied itself to China. Chagla was converted to the seat of a Chinese magistrate, and in 1905 the king of Chagla became one of Tibet’s first rulers to be deposed. A few years later the Chinese authorities burned his palace and decapitated his brother. The king’s own relationship with the new rulers was never secure. Finally he died in sorrow.

After the disruption caused by the elimination of the former king, things had settled; the town returned to its foremost occupation, which was business. After the fall of the Manchu Dynasty, the region fell to the embattlements of ruthless warlords and eventually came under the increasing control of the warlord Liu Wenhui. The warlords, not receiving any salary from the provincial government, monopolized trade in items such as tea, gold, and opium in order to support their soldiers.

Sometimes our elders used the Chinese to frighten us when we children misbehaved. They said, “If you don’t behave yourselves, soon the soldiers of Liu Wenhui will come and take you.” Every child I knew was terrified of this image, and so when the evening conversation of the adults came round to the Chinese, I felt both a fascination and a desire for it to quickly shift to something more familiar.

One early spring day when I was around twelve years old, my abstract imaginings suddenly became a reality. My mother and I were sitting in front of our house cleaning vegetables. Standing up to stretch, I looked around and was surprised...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

- Preface by Joy Blakeslee

- Part I. Before the Years of Sorrow

- Part II. Invasion and Imprisonment

- Part III. Lotus in the Lake

- Part IV. An Unstilled Voice

- Epilogue: The Wheel of Time

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Voice that Remembers by Adhe Tapontsang,Joy Blakeslee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.