- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

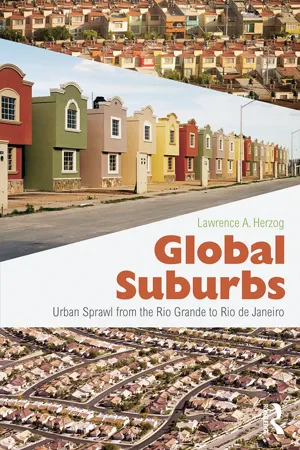

Global Suburbs: Urban Sprawl from the Rio Grande to Rio de Janeiro offers a critical new perspective on the emerging phenomenon of the global suburb in the western hemisphere. American suburban sprawl has created a giant human habitat stretching from Las Vegas to San Diego, and from Mexico to Brazil, presented here in a clear and comprehensive style with in depth descriptions and images. Challenging the ecological problems that stem from these flawed suburban developments, Herzog targets an often overlooked and potentially disastrous global shift in urban development. This book will give depth to courses on suburbs, development, urban studies, and the environment.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE GLOBALIZATION OF URBAN SPRAWL

Urban sprawl has been the defining quality of American urbanism for more than a half century. And now sprawl is spreading across the planet. In 1950, about one-quarter of all Americans in cities resided in the suburbs; a decade later that proportion had increased to one-third. By 1990, half of all metropolitan-based Americans were living a suburban life.1 Today, despite the crescendo of publicity about climate change, sustainable communities, and smart growth, the fact is that, for now and for the foreseeable future, most Americans still live in the suburbs, and still commute to work by car.

Roughly one hundred forty million people, or nearly two-thirds of all U.S. citizens who reside in metropolitan areas, live on the outskirts of cities. This represents almost half of the total population of the U.S.2 After World War II, waves of urban dwellers moved from inner cities to the older first suburban ring. Others migrated to the newer outer tiers during the last quarter century. One report predicted that, of the one hundred million people in U.S. cities who will move by 2050, 25 percent will relocate into existing homes, while the other seventy million will install themselves into sprawling suburban developments. This will require some two hundred million miles of new roads, and add one hundred million more vehicles speeding along our highways.3

Much has already been written about the flawed ecology of American suburbs and urban sprawl. Yet, a new challenge is posed by the globalization of urban sprawl. Since the end of the last century, there has been a global diffusion of the American suburban model, or the idea of an American type suburb (rather than its actual physical form) along with its ecological challenges, across the border to other nations of the Americas.4 These global suburbs repeat many of the errors of U.S. suburbs. They are creating isolated communities increasingly dependent on the automobile. This means that they too are developing the environmental problems that have been well documented in North America. Global suburbs south of the border are also falling under the influence of “fast urbanism,” a dependency on electronics, technology, and consumerism that tends to disconnect citizens from their local ecosystems, while also compromising their sense of community. This, then, is the subject of this book.

I should clarify, at the outset, my use of the term “suburb.” The etymology of the word comes from the Latin suburbium, which referred to Ancient Rome, where poor citizens lived at lower elevations, thus “sub” (under) and “urb” (city), while the rich lived higher up in the hills. In this book I am using “suburb” to refer to the original post-World War II American urban design prototype—single family, detached homes laid out on low density subdivisions, typically with curvilinear street patterns, surrounded by separate shopping centers, schools, offices and other amenities generally only reachable by car. This design model evolved in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. The suburb was typically located in a peripheral district, away from the downtown, and deliberately divided into separate land use zones—residential, shopping, office—all designed principally around automobile travel.5

I consider “suburb” as an urban planning idea that came to represent certain cultural values—privacy, exclusivity, and security. We will see that as one moves south of the border, the word “suburb” itself takes on a different meaning. But the influence of America’s suburban prototype is growing, and that is the point of my book. Whatever term may be used to describe those suburban enclaves emerging on the urban periphery of Mexico or Brazil, the fact is that these “global suburbs” are exploding across the Americas.

Today we see that the basic elements of America’s suburbs— automobile dependency, faster living, consumerism, privatization, and the decline of civic life—are migrating to Latin America. Though the architectures of the emerging elite and middle class “global suburbs” south of the border may take on different densities and visual forms, the ecological problems of North American style sprawl are now materializing on the periphery across the Americas. This evolving pattern demands serious attention.6

For over a half century, the American suburb was viewed as one of the nation’s supreme achievements in modernist twentieth century urban design. Indeed, the American suburban prototype was so admired that architects and planners copied it worldwide. Therefore, I begin by establishing a baseline critique of the contemporary ecologies and landscapes of urban sprawl in metropolitan regions across the Americas. Chapter 2 outlines the environmental and public health crisis that urban sprawl has generated in the U.S. Chapter 3 explores specific ecological problems facing the peripheries of three of the fastest growing cities in the U.S. southwest border region—San Diego, Las Vegas, and Phoenix. In Chapters 4 and 5, I explore the problems associated with the emergence of these suburban prototypes in Mexico and Brazil, the most populous and wealthiest of our Latin American neighbors. Chapter 6 presents some of the main policy directions for moving beyond urban sprawl in the Americas. The final chapter poses some important directions for urban and sustainable planning in the future.

Fast Cities/Fast Suburbs

“In America, we’re all in such a rush. Here (in Paris) they have their lifestyle priorities … Here everyone takes their time.” Thus spoke film-maker Sofia Coppola in a New York Times interview, observing the differences between life in her native Los Angeles and Paris. Coppola explained that, during months of a 2006 Paris shoot for a movie, no matter what kind of deadlines they had on different scenes, her Parisian film crew refused to take a short lunch break. They would always pause to set up a table, pour wine, and “no matter what was happening you could not cut their lunch short.”7 At first Coppola, conditioned by the Los Angeles “time is money” culture, found this frustrating. Eventually, she reported, she learned to enjoy slow eating and the daily respite from the fast lane of movie-making.

The observation that “everyone in America is in such a rush” hints at one critical dimension of twenty-first century urban life in the Americas. We are a nation that has become habituated to fast living on a variety of levels, all of which produce unhealthy outcomes—from the fast foods that harm our bodies to fast fashion and “throwaway chic” consumerism that is wasteful, to fast cities that are environmentally destructive. This ethos of fast living has both environmental and ethical costs that cut across every major layer of our lives—food, clothing, shelter, and ecology.

In modern American suburbia, we are accustomed to travelling fast, typically in our cars and often on our mammoth system of metropolitan region freeways. The average American travels 12,000 miles per year, almost double the distance travelled by citizens in most other industrialized nations.8 We expect to travel fast even if the reality is often different; indeed, much of our travel in the U.S. occurs on increasingly congested freeways to get to distant suburbs. Traffic congestion, mainly along freeways in the urban periphery, has in fact been scientifically linked to higher rates of collisions. Americans also have among the highest traffic fatality rates for industrialized nations.9 Studies show that the more than 40,000 deaths per year in U.S. auto collisions are occurring at higher rates in suburban sprawl counties than in inner city neighborhoods. These mortalities reportedly take place along freeways as well as on feeder roads that lead to freeways, where high speed access and high volume traffic exacerbate the chance of having an accident.10

Americans who commute from the suburbs spend a great deal of time in their automobiles stalled in traffic.11 They also suffer from a “time crunch” by working longer hours than citizens in most other nations. Taken together, longer work hours and the absence of quality time contribute to what I am calling “fast urbanism”—city dwellers living their lives at an accelerated pace within a built environment (spread out suburbs, freeways) that exacerbates this pattern. We must now acknowledge the consequences, including traffic fatalities, higher levels of air pollution, and a variety of public health problems.12 While critics have been pointing to the social and psychological impacts of this “cult of speed” in general,13 I am interested in how it plays out in our contemporary built environment. Our car culture, freeway travel, and the “fast urbanism” lifestyle associated with it are deeply embedded in Western culture, to the point that speed is not merely accepted as normal but is even celebrated, whether it is people, objects, or data moving at high velocities. NASCAR auto racing is one of the two or three most popular sports in the United States. Driving at high speeds is part of the culture surrounding it. The Pocono Celebration of Speed and Design is a spinoff event, an annual east coast racecar festival. The Festivals of Speed are a series of Florida-based celebrations of various forms of fast transportation— racing cars, motorcycles, watercraft, and aircraft. A 2013 TV commercial by AT&T promotes the idea that “faster is better.”14

Applied to living spaces, the above mindset has contributed to “fast urbanism.”15 Life in metropolitan areas is increasingly defined by speed, notably due to the influence of electronic, computer, and other technologies that seem to be accelerating the pace of life. Whether faster is better or not, many Americans like doing things more quickly to save time. But we also begin to detect a contradiction, between “doing more” and “doing faster.” It may not be the case that Americans are hurrying only because they have “less” time, but because they have less quality time or less productive time, or simply less time to freely choose what they wish to do.16

Although central cities have traditionally been the locale for fast paced urban life, the new fast world has now also spread to peripheral, low density urban communities. The dispersed, auto-centric, and malloriented lifestyle of suburbia lends itself quite well to fast urbanism, a point I explore later in this chapter, and in the final policy chapter of this book. “Fast urbanism” is not the only behavioral feature defining America’s (or Latin American) sprawling suburbs; yet, it is a surprising and increasingly important element that has not typically been thought of as a defining feature of the ecology of metropolitan regions.

One might argue that the cores of cities—downtowns like Manhattan, or Chicago’s inner loop—are the places that epitomize fast urbanism: speed, hustle-bustle, noise, crowds, and movement. That was certainly the case in the 1920s and 1930s at the beginning of the modern age, when great cities like New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Boston were booming, as they engaged in the project of modern city-building. In just a decade or two, skyscrapers, subways, bridges, viaducts, train stations, department stores, hotels, theaters, museums, and great squares and parks suddenly rose up, and collectively generated the energy and buzz of excitement that writer John Dos Passos epitomized in his book Manhattan Transfer. Dos Passos’ novel was set in New York City in the 1920s, in all of its dazzling modernity, a mechanical world of machines and power, of fast moving subways and cars, but also a breeding ground of consumerism, restlessness, and greed.17

Figure 1.1 Fast Urbanism: City in a Rush

Source: Photo by Lawrence A. Herzog

However, while central cities are places where things are more concentrated and thus sped up, does it logically follow that suburbs are slower and quieter? Are they idyllic retreats from the fast paced city? Are they still closer to nature, more spread out, and thus more buffered from the hyped-up ambience of downtown? Although the goal of being close to nature and more serene was part of the original reason for building suburbs, over the last three decades suburban sprawl has been systematically shedding many of the features that originally made it slower, and desirable. In cities l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Series Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 The Globalization of Urban Sprawl

- Chapter 2 Sprawl Kills: Ecological Crisis on the Urban Periphery

- Chapter 3 Fast Suburbs in the Southwest Borderlands

- Chapter 4 Sprawl South of the Border: From Mexico City to Tijuana

- Chapter 5 A Global Suburb in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Chapter 6 Beyond Urban Sprawl in a Globalizing World

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Global Suburbs by Lawrence Herzog in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.