![]()

Chapter 1

SCIENTIFIC INFERENCE

Statistics teaching should be integrated with empirical substance. Statistics is not varnish, to be applied after the experiment is done. Statistics is an integral component of the research plan—beginning with choice of problem for investigation. Statistics is important at every intermediate level, including apparatus and procedure, and concluding in the interpretation of the results.

Students almost inevitably come to view the significance test as the be-all and end-all. This test condenses the entire study into a single number of pivotal importance for making claims about what the study shows. A positive answer to the question, “Is it significant?” thus comes to be considered the ultimate goal. “It is significant!” seems all the more potent because “significant” carries undertones of everyday meaning.

The essential question, of course, is what the results mean. The significance test has the necessary—but minor—function of providing evidence of whether there is a result to interpret. What this result may mean depends on considerations at deeper levels.

The more important functions of statistics are in these deeper levels. These more important functions apply at the planning stage, before the data are collected. These more important functions condition the meaning and interpretation of any result that may be obtained. These more important functions of statistics need to be understood in organic relation to the substantive inquiry.

The significance test, in contrast, applies after the data have been collected. It is then too late to correct missed opportunities and shortcomings in the research plan. Finding a significant decrease in felt pain may not be worth much if the placebo control was overlooked. The placebo control may not be valid if the treatment was not “blind.” And even the most careful procedure may founder if you or your research assistant stumbled with the random assignment. These three examples illustrate vital functions of statistics that operate in the planning stage, before the data are collected. This is where statistics is most needed—and most effective.

Some writers argue strenuously against using significance tests. There is something to be said for their argument; it would force people to look more closely at their data. Many statisticians voice similar complaints about the fixation on significance tests and seek to emphasize the more important functions of statistics by avoiding that term and speaking of experimental design, data analysis, and so forth. The significance test has an essential role, however, a role that it performs reasonably well.

The real difficulty is how to integrate statistics-design with empirical inquiry. A very modest number of statistical ideas and formulas will cover most situations that arise in experimental research, as this book will show. What is not so easy is to develop the research judgment to integrate statistical considerations into the planning stage of an experiment. A conceptual framework that puts statistics in its proper place—as an aide to scientific inference—is given by the Experimental Pyramid taken up next.

1.1 EXPERIMENTAL PYRAMID

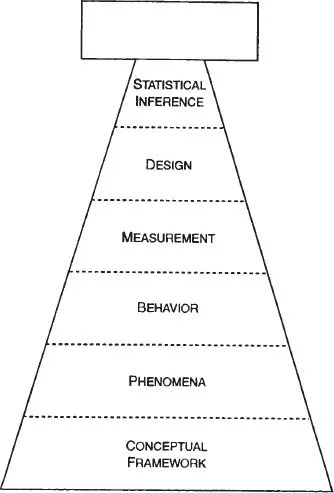

Scientific inference is central to empirical research. Our empirical observations are clues to deeper reality. How we make inferences from these clues may be considered within the Experimental Pyramid of Figure 1.1. Each level of the Experimental Pyramid corresponds to different aspects of empirical investigation. These levels range from statistical inference and experimental design at the top to the conceptual framework at the bottom.

The lower levels are more fundamental. Validity at lower levels is prerequisite to validity at higher levels. The different levels are not separate and distinct, as the dashed lines might suggest; all levels interrelate as facets of an organic whole. Each following section comments briefly on one level of the Experimental Pyramid.

1.1.1 STATISTICAL INFERENCE

The significance test is a minor concern of scientific investigation. It is needed as evidence whether the result you observe is real, rather than chance. Unless you have reasonable evidence that your result is real, there is little point in trying to decide what it means. Before expounding your result, therefore, you owe it to your readers, and to yourself, to show that you have something to expound. This is why the significance test is ubiquitous.

Figure 1.1. Experimental Pyramid

Despite its ubiquity, the significance test is only a minor aspect of substantive inference. What your result means depends on substantive considerations: What experimental task you choose, what response measure you use, your control conditions, and so forth. Such substantive inference depends on considerations at more basic levels of the Pyramid.

Even within statistical inference, the significance test has a minor function. More important functions of statistical analysis concern other aspects of reliability, especially confidence intervals that describe a sample mean as an interval of likely error. Even more important is validity. When measuring each subject under multiple conditions, for example, statistical inference is essential for dealing with sticky problems of practice, adaptation, and transfer from initial conditions that confound the response to conditions that follow.

Validity, reliability, and other functions of statistical analysis share one common property. Unlike the test of significance, these other functions operate before or during the data collection. This is because these other functions are interwoven with substantive considerations at the lower levels. Some of these are taken up in the following discussions of the other levels of the Pyramid. Others will appear in the later sections on validity, reliability, and samples.

1.1.2 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

The experimental design mirrors and embodies questions being asked by the investigator. Almost the simplest design involves two treatments, experimental and control, the question being whether the experimental treatment has real effects on the behavior. The significance test aims to provide an objective answer. But the design is more basic—it determines what the data mean.

It is at this design stage—before any subject is run—that statistics has its greatest value. Most valuable is the function of controlling variables that might confound the interpretation. One notable example is the principle of random assignment discussed in Section 1.4.1, which has the vital function of controlling unknown variables.

Statistics can also help at the design stage by calculating the probability of success/failure, formally called the power of the experiment. If this power calculation indicates the experiment is too weak to detect the expected effect, design changes may be possible that will yield adequate power.

Still another design function of statistics arises in analysis of multiple determination. Multiple determination is fundamental in psychological science because most behavior depends on joint action of two or more variables. Among the questions of interest are whether two variables “interact,” and if so, in what way. One major achievement of twentieth century statistics has been the development of tools to study multiple determination (Section 1.5).

Although the questions asked by the investigator are defined formally in the design, their substantive meaning depends on what is measured. Substantive meaning requires consideration of the next two levels of the Pyramid.

1.1.3 MEASUREMENT

Measurement has a unique role in the Experimental Pyramid. It is the link between the world of behavior and the world of science. Measurement is thus a transformation, or mapping, from the real world of objects and events to a conceptual world of ideas and symbols.

This measurement transformation is a vital feature of science. Our measurements are produced by our experimental task, apparatus, and procedure. Measurement is thus grounded in experimental specifics that define the transformation from the behavioral world to the conceptual world.

This empirical grounding of measurement will be emphasized in the later discussions of validity and reliability. These two concepts subsume virtually all of measurement. Reliability represents intrinsic informational content of our measurements; validity represents substantive or conceptual informational content. Both depend on the three lower levels of the Pyramid, beginning with the level of behavior.

1.1.4 BEHAVIOR

Behavior is the central level of the Experimental Pyramid. Behavior, however, is not autonomous. It is partly created by the investigator’s choices in the experimental setup, which include organism, task, apparatus, procedure, response measure, and so forth. These choices determine what the measured data mean.

Progress in any science depends on development of “good” experimental setups. Among the criteria of a good setup are importance of the behavior, its simplicity and generalizability, statistical properties of the response measure, and cost, including time and trouble.

Pavlov’s studies of conditioned salivary reflexes in dogs are famous because of the seeming simplicity of the behavior and its presumed generality, not merely as a base for psychological theory, but also as a model and tool for analysis of behavior. The white rat is more popular, partly because of cheapness and convenience, but also because the rat exhibits a broad spectrum of behaviors common with us humans.

The importance of choices in the experimental setup is visible in controversies in the literature. Many, perhaps most, are concerned with confoundings that may undercut the interpretation of the results. These controversies provide useful lore for newcomers in any field.

The choices in the experimental setup are in mutual interaction with the upper levels of the Pyramid. These choices are determiners of the quality and validity of the response measure, as well as its reliability. Mutually, requirements at upper levels guide choices at the behavioral level. The final setup requires compromises between aspiration and practicality, compromises that not infrequently must be made without adequate information. Early work on some problems can look strangely crude until it is recognized how subsequent work transformed our knowledge system.

Experimental setups should be treated as a matter of continuing development. A major impetus to such development stems from arguments over confounding and validity. Similar arguments over reliability would also be useful. In experimental psychology, however, they remain infrequent—in dark contrast to the attention lavished on the significance test.

1.1.5 PHENOMENA

We usually aim to study some phenomenon—information integration, memory, color vision, intuitive physics, language, social attitudes, and so forth. What we actually study is some observable behavior, which we hope is a good measure of the phenomenon. The difference is one of kind: between the fact of behavior and the name given the phenomenon, which usually carries a conceptual interpretation of the behavior.

We usually conflate the behavior and the phenomenon, presuming that the name we impose on the behavior is warranted. This presumption is more than a convenience; it is the most important determinant of our choices in the experimental setup. But this presumption may be unwarranted. The innumerable arguments over confounding in the literature demonstrate the difference between behavior and phenomenon. This central issue of confounding is discussed in Section 1.2.3 and Chapter 8 is devoted to it.

A related reason for distinguishing behavior from phenomenon is that performance in any setup involves other abilities besides the focal behavior. This is a recurrent difficulty in studying young children’s development of concepts such as time and number. Younger children may be handicapped by lesser development of verbal ability, for example, that interferes with their performance on the focal concept. Such confounding is frequent in Piaget’s work, to take one example from Chapter 8. This example has statistical relevance because statistical design techniques can remove some of these confoundings.

A further aspect of the behavior-phenomenon distinction concerns generality. Any given setup must be restricted to one or a few exemplars of the phenomenon. Generality for other exemplars is a primary desideratum. Studies of learning, for example, usually concentrate on a single task, hoping the results will hold for other tasks. Sometimes this happens, sometimes not. Pavlov’s salivary reflex, surprisingly, yielded findings and principles of considerable generality. Ebbinghaus’ rote memory tasks, on the other hand, were a disappointment in the search for general principles of memory.

The most important problems in experimental analysis are at the interface and interaction between the levels of behavior and phenomena. This is widely understood, but this understanding remains largely localized in the lore of particular substantive areas. Such lore represents general problems of method that deserve more focused and systematic discussion than they receive. How the investigator resolves these problems is a primary component of scientific inference.

1.1.6 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The base of the Experimental Pyramid is the conceptual framework of the investigator. This framework is most apparent in the interpretation of results in the discussion section of an article. This framework is a major determinant of choices at all upper levels. The experimental design, as one example, is often constructed specifically to support one theoretical interpretation and eliminate alternatives. Studies that are primarily observational or exploratory generally stem from and embody preconceptions about what constitutes interesting aspects of behavior.

Conceptual frameworks are strong determiners of what phenomena are studied. Learning theory was the dominating framework during 1930–1960, but suffered eclipse in the later cognitiv...