![]()

PART I:

INTRODUCTION TO MARKETING

PLANNING

![]()

Chapter 1

The Importance of Marketing Planning

MARKETING PLANNING IN ACTION:STARBUCKS

Most Americans have heard of the company Starbucks. The proliferation of Starbucks stores has been the subject of late-night television jokes and watercooler discussions, yet the company continues to open an average of three stores every day. When hearing about the company's debut on the Fortune 500 earlier this year, its founder, Howard Schultz, admitted that it would be arrogant to say that ten years ago he thought Starbucks would be where it is today, but from the very beginning of the company's inception, his goal was to dream big. And dream big it does. In fact, the seemingly oversaturation of many retail markets is the very goal of his business strategy.

Starbucks' strategy is surprisingly straightforward: “Blanket an area completely, even if the stores cannibalize one another's business.” Today the company has 6,000 stores in more than thirty countries despite the fact that it does not franchise. Its goal is to have a minimum of 10,000 stores worldwide. Yet Schultz's goal for the company has as much to do with its philosophy of business as it does in becoming a multinational icon. Starbucks strives to be the kind of company everyone wants to work for, where even the part-time employees receive benefits such as health insurance and stock options. This nurturing environment transfers over to the employee's belief in the company, its product, and sense of community, which in turn provides an atmosphere that is the key to success in service companies.

The omnipresence of Starbucks adds to its success in spite of the fact that stores may literally be across the street from each other. When a new store opens it will often cannibalize a sister store, sometimes up to 30 percent of the existing store's business. Although this may seem to be an inappropriate strategy to some, it does provide the company several operational benefits. With stores so close together it cuts down on delivery and management costs, it can help to shorten customer lines in each store (particularly during the morning rush), and helps to increase total customer traffic. In a given week, 20 million people will buy a cup of coffee from a Starbucks store. The typical customer visits Starbucks four to five times each week—an unheard of frequency for customer visits to a retailer.

The proliferation of stores also helps to bring a sense of “presence” to the customer, similar to the impact of multiple shelf facings of a product in a grocery store. The fact that Starbucks is everywhere and readily available contributes to its brand awareness despite the fact that it spends only 1 percent of its annual revenues on advertising. Typically, retailers spend close to 10 percent on ads each year.

The company has also managed to have a significant impact on the way America views coffee and community. Starbucks' $3 cup of coffee was viewed as a West Coast fad that would soon die out. It is far from a fad, and this premium pricing strategy certainly appeals to a specific segment of the total coffee market. Starbucks has successfully created a niche for a premium-priced product by offering consistent quality and a neighborhood conclave. It appears to serve that niche well, even though it captures just 7 percent of the total coffee-drinking market in the United States and less than 1 percent abroad.

When Schultz took Starbucks public in 1992, the company had only 165 stores around Seattle and in neighboring states. Eleven years later it made its first appearance on the Fortune 500. What is Schultz's goal for the next ten years? “We want to become one of the most respected and recognized brands in the world. Like Coke,” he adds.1

INTRODUCTION

Planning is one of the keys to success of any undertaking, and nowhere is it more important than in business. Every study dealing with business failures uncovers the same basic problem, whether it is called undercapitalization, poor location, or simply a lack of managerial skills. All these problems have their roots in planning. Marketing is one of the most important types of business activity that must be planned. The marketing plan defines the nature of the business and what that organization will do to satisfy its customers' needs in the marketplace. As such, the marketing plan is not just an “academic” concept of use to educators, but is a ruthlessly practical exercise that can spell the difference between success and failure to all types of organizations—big or small, producing for businesses or consumers, goods or services, for-profit or not-for-profit, offering domestic or international.

For planning to be successful, it must be founded in a root philosophy or conceptual framework that provides a basis for analysis, execution, and evaluation. A thorough understanding of both marketing and planning must precede any manager's attempt to develop and execute a marketing plan. This chapter focuses on marketing and planning and their relationship in the planning process.

WHAT IS MARKETING?

Various definitions of marketing have evolved over the years, but one that appears to be fairly complete is as follows: Marketing directs those activities that involve the creation and distribution of products to identified market segments. Several key words in this definition need further explanation. First, marketing directs. This is a managerial perspective rather than a residual perspective, which is concerned only with what has to be done to get goods and services to customers. Thus, marketing is not just a group of activities but more specifically is activities that are controlled in their execution to attain identifiable objectives. Second, marketing involves the performance of specific activities or functions. These functions constitute the work or substance of what marketing is all about. To be involved in marketing means to be involved in the planning, execution, and/or control of these activities.

Third, marketing involves both creation and distribution of goods and services. Although the product or service is actually created by the production function, marketing personnel are very much concerned not only about the creation of goods and services from a physical perspective but also from the perspective of customer need. Marketing needs to have a vital role in creation as well as distribution of goods and services. In fact, a well-conceived product or service makes the rest of the marketing tasks easier to perform.

Finally, marketing's concern is with customers and meeting a need in the marketplace. However, its concern is not just with any or all customers but particularly with those preselected by management as the market segment(s) on which the company will concentrate. Thus, specific customers with their specific needs become the focal point of marketing activities.

Marketing Orientation

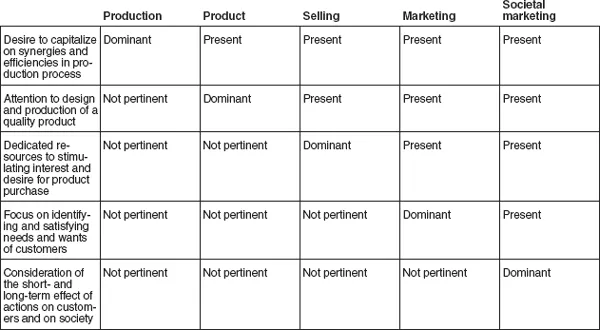

True marketing thought focuses on addressing the needs and wants of a targeted segment of the market. Other business philosophies or orientations may be put into practice by managers with marketing titles, but they do not reflect authentic marketing thought. Exhibit 1.1 shows five different business orientations that have been used as the operating philosophies behind management decision making. The term dominant identifies the core objective that gives the orientation its name. Present means that the orientation includes that objective, but does not use it as the centrally controlling goal in orienting the manager's thoughts about his or her company, its products, and its customers. Notpertinent means that a particular objective has no relevance, pertinence, or connection with the orientation described. This exhibit makes it clear that the production, product, and selling orientations are internally driven. Managers using such orientations are determining what they want to dictate to the market. Only the last two orientations—marketing and societal marketing—contain the elements of an “outside-in” or market-driven philosophy, which stresses discovery of market opportunities, marketplace input regarding the organization's claim of a competitive advantage, and the integration of effort across all areas of the organization to deliver customer satisfaction. These two orientations reflect the competitive realities facing organizations of all types.

The societal orientation is particularly well-suited to internal and external environmental forces currently facing managers. It includes all of the positive contributions of the other four orientations, but adds concerns for the long-term effects of the organization's actions and products on its customers, as well as the desire to consider the effects of the organization's actions on society at large. In other words, it recognizes the sovereignty of the marketplace and uses both deonto-logical (rights of the individual) and teleological (impact on society) ethical frameworks as part of the decision-making process. Putting this philosophy in practice requires a planning procedure that transforms this consumer orientation into marketing activities.

EXHIBIT 1.1. Business orientations

WHAT IS PLANNING?

Anyone studying managerial functions soon learns that although the list of specific functions may vary from author to author, one function common to all lists is planning. Planning may be defined as a managerial activity that involves analyzing the environment, setting objectives, deciding on specific actions needed to reach the objectives, and providing feedback on results. This process should be distinguished from the plan itself, which is a written document containing the results of the planning process. The plan is a written statement of what is to be done and how it is to be done. Planning is a continuous process that both precedes and follows other functions. Plans are made and executed, and then results are used to make new plans as the process continues.

Reasons for Planning

With today's fierce business competition and economic uncertainty, traditional management approaches are becoming less effective. In the past, the attention was on boosting profit by cutting expenses, conducting operational efficiency, and doing things right. Downsizing the firm's workforce to cut costs became a popular reaction to profit squeezes for many organizations during the late 1980s and 1990s. However, it became obvious only later that such efforts to reduce costs may be sacrificing long-term competitive strengths for short-term financial gain. Gains in efficiency cannot deliver long-term benefits unless they are coupled with gains in effectiveness. A survey of 250 senior executives revealed that profit management in the future ...