![]()

Chapter 1

Preamble

1.1 Setting the scene

For the past three decades or so, the causative construction has truly been one of the most recurrent research topics studied by linguists of diverse theoretical persuasions. This is not entirely surprising in light of the fact that analysis of the causative construction calls for a careful synthesis of morphology, syntax, semantics, and even pragmatics. In fact, the causative is a kind of ‘testing ground’ where grammatical theories are pushed to their limits or even brought to their logical conclusions. For instance, the sixties and seventies witnessed the rise and fall of Generative Semantics. It was indeed an analysis of the causative that initially provided the theoretical basis for (highly transformational) Generative Semantics. Ironically, it was none other than the analysis of the causative that precipitated the demise of Generative Semantics as a viable grammatical theory, and subsequently called the whole framework of Transformational Grammar into question. As a result, a number of nontransformational or minimally transformational generative theories have now sprung to prominence (cf. Newmeyer 1980 [1986]).

The state of affairs is not so different in the eighties and nineties. The causative construction still remains as one of the main research topics which many linguists of both formal and functional orientations engage in.1 For instance, the causative raises intriguing questions of theoretical significance in Government and Binding (GB) theory (e.g. Marantz 1984, Baker 1988). In Relational Grammar (RG), the causative is discussed with a view to developing universal grammatical relation changing laws or principles (e.g. Gibson and Raposo 1986, Davies and Rosen 1988). It is also one of the favourite research topics in Lexical-Functional Grammar (LFG) in that it is claimed to provide support for the lexical approach to what are regarded as syntactic problems in other generative theories (e.g. Mohanan 1983) or in that it poses interesting theoretical questions concerning the mapping between argument structure and syntactic structure (e.g. Alsina 1992). The scene does not change much within the ‘functional’ school either. In fact, Comrie (1975, 1976b, 1981a [1989]), one of the pioneers in the functional-typological framework, deals with causatives and claims that the hierarchy of grammatical relations found crosslinguistically to be operative in relative clause formation can also be used to predict the grammatico-relational fate of the causee NP. Undoubtedly, the causative will continue to fascinate and preoccupy linguists of diverse theoretical backgrounds for years to come.

Naturally, the corollary of such a magnitude of research on the causative is a vast amount of literature on it. Therefore, it behooves the investigator to justify his reason(s) for undertaking further large-scale work on this intensively studied area.

All previous theories of causative constructions address one or more of the following issues:

(a) the formal (or morphological) classification of causatives, i.e. lexical, morphological, and syntactic causative types (Nedyalkov and Silnitsky 1973, Shibatani 1975, 1976c);

(b) grammatical and semantic correlates of (a), e.g. productivity, lexical decomposition, etc. (Dowty 1972, 1979, Shibatani 1975, 1976c, Foley and Van Valin 1984);

(c) the grammatico-relational fate of the causee NP or the subject NP of the (underlying) embedded clause, i.e. the hierarchy of grammatical relations (Aissen 1974a, Comrie 1975, 1976b, 1981a [1989], Gibson and Raposo 1986, Baker 1988);

(d) semantic types of causative, e.g. direct, indirect, manipulative, directive, etc. (Shibatani 1975, 1976c, Talmy 1976);

(e) semantic characterizations of the causee NP (vis-à-vis the causer NP), e.g. animacy, volition, control, etc. (Shibatani 1975, 1976c, Givón 1976b, 1980, Comrie 1981a [1989], Cole 1983);

(f) diagrammatic iconicity in lexical, morphological, and syntactic causatives (Givón 1980, Foley and Van Valin 1984, Haiman 1985a);

(g) amalgamation of the higher and lower clauses, or the higher and lower predicates, i.e. predicate raising, clause union, incorporation, etc. (Aissen 1974a, Gibson and Raposo 1986, Baker 1988); and

(h) (theory-specific) issues arising from (g) (Gibson and Raposo 1986, Baker 1988, Alsina 1992).

Although it is not meant to be exhaustive, the preceding list represents most of the major current issues concerning the causative.

As can be seen from the list, these theories are all concerned with grammatical aspects of the causative (i.e. (a), (b), (c), and (g)), semantic aspects of the causee and its status vis-à-vis the causer (i.e. (b), (d), (e), and (f)), or theory-internal problems arising from the construction (i.e. (g) and (h)). For instance, three prototypical types — lexical, morphological, and syntactic — are recognized in the morphological classification of causatives, which in fact forms the basis of the traditional typology of causatives. The lexical causative type involves suppletion. In English, for example, there is no formal similarity between the basic verb die and the causative one kill, as in:

| (1) | ENGLISH |

| a. | The terrorist died. |

| b. | The policewoman killed the terrorist. |

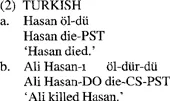

The morphological causative involves a more or less productive process in which causatives are derived from noncausative ones by adding a causative affix. Turkish provides a classic example of this type of causative, as in:

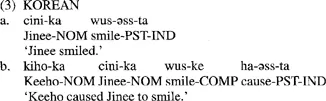

In (2.b), the causative suffix -dür is attached to the basic verb öl-, whereby the causative verb öl-dür is created. In the syntactic type of causative, there are separate predicates expressing the notion of cause and that of effect. Korean provides an example of this last causative type, as in:

The boundary between the two predicates (hence between the two clauses) is clearly indicated by the element -ke in (3.b). The lexical causative represents the nil distance between the expressions of cause and effect. The syntactic causative represents the maximum distance between the two expressions. The morphological causative occupies the middle point between the lexical and syntactic causative types, as it were. Languages may not, of course, ‘fit neatly into one or other of these three types, rather a number of intermediate types are found’ (Comrie 1981a [1989]: 159–160). Thus, these causative types are understood to represent three ‘focal’ points on the continuum of the physical or formal fusion of the expression of cause and that of effect (e.g. Bybee 1985a, Haiman 1985a).

However, what can be learned about causation from this morphological parameter? Not much, since, for one thing, it is not unique to the causative construction. Haiman (1985a: 102–147) demonstrates that the same kind of formal fusion is found crosslinguistically in the expressions of inalienable and alienable possession, coordination, complementation, etc. Givón (1980, 1990: 826–891) identifies a similar kind of formal fusion in what he refers to as interclausal coherence (i.e. degrees of bonding between clauses). In a similar vein, Foley and Van Valin (1984: 264–268) capture the formal fusion found in various clause linkage types by means of what they call the Syntactic Bondedness Hierarchy (ranging from the most tightly knit clause linkage to the most loosely knit). Bybee (1985a: 12) also proposes the continuum of fusion ranging from lexical to syntactic in order to explain the crosslinguistic distribution of verbal categories, such as tense, aspect, etc. The three causative types can, in fact, easily be mapped onto, for instance, Bybee’s continuum of fusion. Thus, it is very unlikely that the morphological typology will be able to provide much insight into causation per se (cf. 5.2).

Indeed, why that is so can be better understood by examining various attempts that have been made over the years to correlate the morphological typology directly with various semantic causation types (e.g. Shibatani 1975, Talmy 1976). One such semantic parameter is the distinction between ‘direct’ causation and ‘indirect’ causation. The distinction is based on ‘the mediacy of the relationship between cause and effect’. The temporal distance between cause and effect may be so close that it becomes difficult to clearly divide the whole causative situation into cause and effect (Comrie 1981a [1989]: 165). For example, if X pushes the vase over, and it falls, the relation between cause (i.e. X’s pushing the vase over) and effect (i.e. the vase’s falling) is very direct. On the other hand, the temporal relation between cause and effect may also be more distant, in fact so distant that it is not easy to clearly divide the whole causative situation into the two parts, i.e. cause and effect. For example, X, an amateur motor mechanic, fiddles with Y’s car so that unfortunately the brake begins to work ineffectively, and a few weeks later, Y is injured in an accident due to the failure of the brake. In this case, the relation between cause (i.e. X’s fiddling with the car) and effect (i.e. Y’s injury) will be very indirect. Languages are generally known to formally distinguish direct causation from indirect causation (Haiman 1985a: 108–111, 140–142). In order to express direct causation, languages tend to use the causative which exhibits a higher degree of fusion of the expression of cause and that of effect, whereas in order to express indirect causation, languages tend to use the causative in which there is a lower degree of fusion of the expression of cause and that of effect. In Nivkh, for instance, lexical causatives are used to encode direct causation, and morphological causatives, indirect causation (Comrie 1981a [1989]: 165–166). To put it differently, there is an iconic relation between the morphological typology and the semantic causative types in question (Haiman 1985a: 108–111). However, this kind of investigation does not directly concern causation per se, but rather only the temporal distance between cause and effect. Although it may have enriched our overall understanding of causation, the temporal distance between cause and effect does not explain the nature of causation itself.

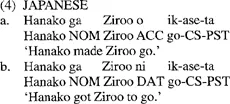

Another semantic parameter that is often discussed with regard to causatives is the degree of control exercised by the causee in a causative situation. This is reflected grammatically in the signalling of the causee or the case marking of the causee NP in some languages. So, in Japanese, the accusative case o is used to mark the causee when it exercises a lower degree of control; when it exercises a higher degree of control, the causee is marked by the dative case ni, as in:

In (4.a), the causer may not rely on the causee’s intention to realize the event of effect (i.e. Ziroo’s going), whereas in (4.b) the causee retains a certain amount of control over the event of effect so that the causer may have to appeal to the causee’s intention, as it were. So, the o-version in (4.a) may ‘imply more coercive causation as opposed to less coercive causation of direction-giving represented by the ni-version’ in (4.b) (Shibatani 1990: 309). Interesting as that may be, what can be discovered about causation ...