![]()

1

Introduction

According to Guinness’ Book of Records, the longest moustache ever to flourish under the nose of man was grown in India and spanned a prodigious 102 inches.

Unless you are an avid afficionado of trivia, the preceding sentence has probably told you things you didn’t know before. In particular, it has told you the length and location of the world’s longest moustache. It has also told you that these facts are recorded in Guinness’ Book of Records. Let’s zero in for a minute on one of these facts: the moustache length of 102 inches. Close your eyes for a few seconds and then try to recall this number. Chances are you are able to do it. Chances are that you could also, if asked, recall it in 10 minutes. If you spend enough time right now memorizing the number, you could probably also remember it next month.

A human being presented with some new fact is often able to reproduce the fact some period of time later. During that period of time, the fact, or some representation of it, must have been stored somewhere within the individual. Therefore, humans possess memory.

What is memory? Implicitly, we have defined memory above as some kind of repository in which facts (information) may be retained over some period of time. If this simple definition is accepted, however, memory is possessed not only by humans but by a great number of other things as well. Trees, for example, have memory, for a tree retains information about its own age by adding a new layer or ring to itself every year. A tree also occasionally stores information about events that happen to it in its lifetime. For instance, suppose lightning strikes it one night, leaving a black disfiguring gash in its trunk. The gash remains forever as part of the tree, thereby providing a “memory” of the event.

We feel in our hearts, however, that the memory possessed by a human is somehow more sophisticated than the memory possessed by a tree and, with a little thought, we can enumerate some differences between tree memories and human memories. First, a tree is severely limited in terms of the type of information it can put into its memory. A tree stores information about its own age in its “memory” (and occasionally information about lightning strikes), but it cannot store information about the world’s longest moustache. (Some trees store information about romances—for example, GL loves BF—but this sort of information is carved into the tree by humans and not put there by the tree itself.) Humans, in contrast, are capable of putting any arbitrary information in their memories; you saw evidence of this a few minutes ago when you stored information about the world’s longest moustache.

A second difference between trees and humans is that a tree does not have the ability to retrieve information from its memory and present the retrieved information to the outside world on request. No matter how many different ways I ask a tree how old it is, it won’t tell me. I have to cut it down, count the rings, and find out for myself. In contrast, if I request information residing in the memory of a human, he1 has the ability to retrieve that information and communicate it to me. The specific means by which the request for information is made and the specific manner in which the information is communicated may differ in different situations. If, for example, I want to know your name, I simply ask you and you communicate it to me vocally. However, if I’m in a Paris restaurant and want information about where the bathroom is from a waiter who speaks no English, my request for this information and his communication of it to me may take the form of elaborate gestures. Other idiosyncratic means of requesting information may be necessary when, for example, a mother is confronted with an infant too young to speak. In each of these cases, however, the person from whom the information is being requested has the capability of retrieving it and communicating it in one way or another.

In short, a human has not only a memory but an elaborate memory system. We have just noted a few things about this system: that it has the capability of putting new information into a memory and of retrieving information already in memory. An additional characteristic of the system not noted above is that some information in memory seems to become less available over time. In 1972, I lived in New York and had a New York telephone number. In 1972, that number was available to my memory system. Now it’s not. In common parlance, things get forgotten.

The subject matter of this book is a detailed specification of the human memory system. Basically, we shall try to describe how the system puts information into memory, how it retrieves information from memory, and what happens to information resident in memory.

THE INFORMATION-PROCESSING APPROACH

We have been discussing memory in terms of information, which has been loosely viewed as some kind of substance that is put into memory, retrieved from memory, lost from memory, etc. This information-oriented way of talking about memory is relatively recent, having been used by theorists only since the 1950s. Two major events were in large part responsible for stimulating this approach: the development of information theory and the development of computers. Before we proceed, we shall briefly describe the relevance of these two events to the information-processing approach to memory.

Information theory. We all have an intuitive view of what information is. When I tell you something you didn’t know before, you’ve acquired information. For example, you acquired information when you read about the length of the world’s longest moustache. However, suppose I tell you that the world’s southernmost continent is Antarctica. Have I told you something? Yes. Have you acquired information? No, because I didn’t tell you anything you didn’t already know.

In 1949, Shannon and Weaver took this intuitive notion of information and quantified it; that is, they showed how information could be made measureable. To quantify information, the first thing needed was a unit of measurement. To measure volume, we have cubic centimeters; to measure distance, we have inches. To measure information, we have bits. A bit is defined as: the amount of information that distinguishes between two equally likely alternatives. I’ve just flipped a coin. In telling you that the outcome of the flip was tails I’ve conveyed to you 1 bit of information, since prior to my telling you the outcome there were, as far as you were concerned, two equally likely outcomes to the flip.

More generally, suppose that some situation has N equally likely outcomes. (For example, if I roll a die, N = 6; if I tell you I’m thinking of a digit, N = 10; if I tell you I’m thinking of a letter of the alphabet, N = 26.) The amount of information you acquire when appraised of the outcome of the situation can be expressed by the following equation:

where I is a measure of the amount of information. This equation may be read: “the amount of information is equal to the base-two logarithm of the number of possible alternatives. Table 1.1 shows the amount of information in various stimuli according to this equation.

Readers not familiar with logarithms need not worry. For the purposes of this book, it is not important to know exactly how to quantify information. What is important is the idea that the information contained in various stimuli can be quantified and we can therefore see that some stimuli (for example, letters) contain more information than other stimuli (for example, digits).

TABLE 1.1

The Amount of Information in Various Types of Stimuli

Stimulus | N = number of alternatives | I = log2 N |

Coin flip | 2 | 1.00 |

Digit | 10 | 3.32 |

Letter of the alphabet | 26 | 4.70 |

U. S. state | 50 | 5.65 |

Playing card | 52 | 5.75 |

Squares of a checkerboard | 64 | 6.00 |

Recoding of information. Let us go back to our coin flip. Suppose I flip a coin and the outcome is tails. As we have seen, the outcome represents 1 bit of information; however, this 1 bit may take on a variety of physical representations. The coin itself lying on my wrist is one physical representation. If I say “tails,” that is another representation of the same information.

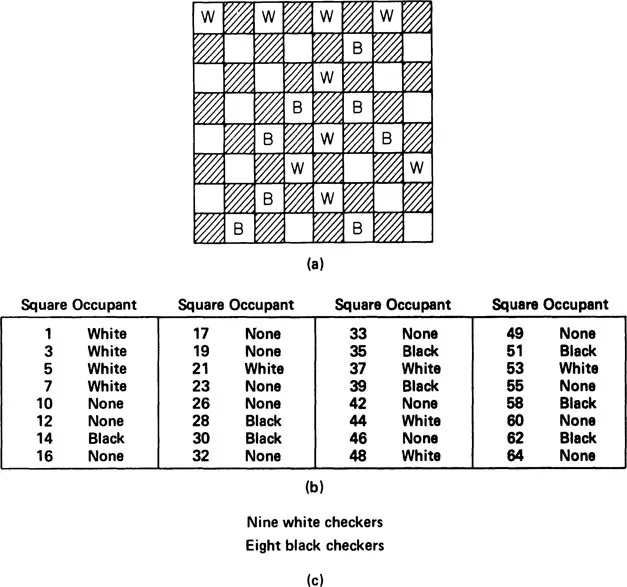

Changing the form of the same information from one representation to another is called recoding. Consider a somewhat more complex array of information: the configuration of a checkerboard. Figure 1.1a shows one representation of the same information; Figure 1.1b shows quite a different representation of the same information. To get Figure 1.1b, I took the information in Figure 1.1a and recoded it. Figure 1.1c shows yet another representation that is a recoding of the information in Figure 1.1b. Notice an interesting thing: the recoding from Figure 1.1a to Figure 1.1b has preserved all of the original information. Therefore, Figure 1.1b could, if desired, be used to produce Figure 1.1a as well as vice versa. In the recoding from Figure 1.1b to Figure 1.1c, however, a good deal of the original information—namely, the position of the checkers—has been lost, and Figure 1.1c could not be used to reconstruct Figure 1.1b or Figure 1.1a. When information is recoded, therefore, it is possible for some of the original information to be lost.

FIGURE 1.1 Recoding of information. Each panel provides information about the configuration of checkers on a checkerboard: (a) representation by a picture; (b) representation by a list; (c) representation in terms of numbers of black and white checkers.

In subsequent chapters, when we discuss the memory system, we shall see that the system includes components or stages of memory and that information passes from stage to stage. In passing from stage to stage, information is recoded, and in the process of being recoded, a good deal of information gets lost.

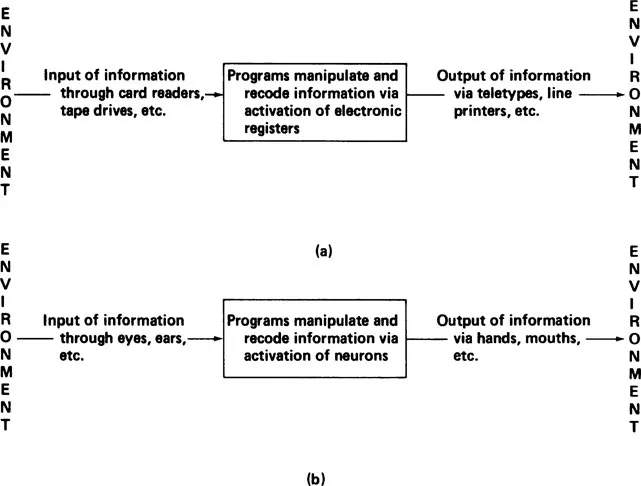

Computers. An important tool for any scientific theory is a model or physical analog of that about which one is attempting to theorize. For the atomic theory of Niels Bohr, the model is a tiny solar system with planets (electrons) spinning in their orbits about the sun (nucleus). For stimulus–response psychologists, the model is a telephone switchboard with calls coming in from the environment (stimuli) being routed via switchboard connections to the appropriate telephone (responses). For psychologists working within an information-processing framework, a computer provides an apt analogy of what is happening inside a person’s head. The old view of a computer as a “giant brain” is taken seriously, except that it is somewhat reversed—a human brain is seen as a “midget computer.” Both computers and people are information-processing systems, and Figure 1.2 shows a schematic view of the analogy. Both computers and humans take in information from the environment. Computers do this using card readers, tape drives, etc., whereas humans do it using their sense organs. Inside a computer, the information from the environment is manipulated, recoded, and combined with other information already there. This is done via activation of electronic registers. Inside a person, information is manipulated, recoded, and combined with other information already there. This is done via activation of neurons. Finally, a computer outputs information to the environment via output devices, such as teletypes and line printers. Likewise, humans output information to the environment via such output devices as mouths and hands.

FIGURE 1.2 Similarity of information processing in computers and in humans: (a) computers; (b) people.

To extend the analogy, a distinction can be made at this point between computer hardware and computer software. Computer hardware is that which is built into the computer at the time it is made—the nuts and bolts, the metal frame, the transistors, resistors, and circuitry. Analogously, the “hardware” of a person consists of a body, of bones, of a complex system of neural circuitry, and so on. In contrast, computer software consists of programs, which cause the computer to manipulate information in various ways. A program is simply a series of instructions, written in a language the computer is built to understand, that tells the computer precisely what t...