- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This ambitious survey covers all aspects of the period in which English society acquired its modern shape -- industrial rather than agricultural, urban rather than rural, democratic in its institutions, and middle class rather than aristocratic in the control of political power. For this revised edition the footnotes and bibliography have been fully updated, and the entire text has been reset in a larger and more attractive format. An ideal introduction to the subject, it masters a huge amount of material through its clear structure, sensible judgements and approachable style.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Age of Urban Democracy by Donald Read in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Victorian Turning Point, 1868-1880

Chapter 1

Introduction

‘The revolution of our times’

1

The chronological mid-point of Queen Victoria's long reign fell in 1869 - more than thirty years on the throne, over thirty still to pass. Of course, the Victorians did not know that the reign still had so much time to run. But long before its ending they were to become aware that the lengthening span of years from the queen's accession in 1837 possessed a unity only through the accident of her longevity. At the time of her Golden and Diamond Jubilees in 1887 and 1897 the great changes which had taken place since the start of the reign were frequently described. Lord Salisbury remarked as Prime Minister in 1897 how Queen Victoria had 'bridged over that great interval which separates old England from new England'. This transition from the 'old' to the 'new' had been not only continuous but also accelerating, so that each Victorian generation seemed to be the more separated from its predecessor. Society, industry, agriculture, religion, ideas, politics - everything seemed to be in flux. James Baldwin Brown, a leading Congregationalist minister, tried in First Principles of Ecclesiastical Truth (1871) to measure 'the revolution of our times'. Society (he wrote) seemed to be seeking a new basis 'instead of expanding on the old bases. Compare the throng of things which now press upon you daily, the crowd of interests which demand attention, and force themselves into the council chamber of your thoughts, with the narrower circle of pursuits, pleasures and ideas which occupied our fathers little more than a generation ago'. 'The real power of the revolution,' continued Brown, was mental more than material. 'The submission of every thing and every method to the free judgement of reason, by the menstrum which a free Press, a free Platform, and a free Parliament supply.' Certainly, the power of traditional authority in church and state had been receding since the seventeenth century. Now it was being rapidly displaced by the power of inquiry, observation, and opinion. In intellectual and scientific fields the numbers engaged were still small; but the interested audience was growing fast. And the public opinion which could influence political decisions was becoming larger with every year.

Yet where was all this leading? Belief in progress, in 'improvement', had waxed strong during the first half of the reign, 'age after age, making nicer music from finer chords'. But confidence seemed to be weakening by the late 1860s. 'We shall "improve" still faster than we have done for the last thirty years. And how much better shall we be for it at the end?' (Leeds Mercury, 25.8.1869). Uncertainty was increasingly to characterize the whole period from 1868 to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. 'It is the year of grace 1868,' wrote Anthony Trollope, the novelist, in the March number of St. Paul's magazine; 'the roar of our machinery, the din of our revolutions, echoes through the solar system; can we not, then, make up our minds whether our progress is a reality and a gain, or a delusion and a mistake?'

As foreign economic and political competition intensified, the relative decline of British power was to become indisputable. The victory of the Federal forces in the American Civil War (1861-5) had left the United States ready at last to exploit its huge potential in men and resources. Bismarck was working through the 1860s to unify Germany, and the German Empire was proclaimed in 1871 after the swift collapse of the French Second Empire during the Franco-Prussian War. Imperial Germany was to prove a much stronger rival than Imperial France. When Lord Palmerston - the veteran protagonist of a confident foreign policy - had died in 1865 it was rightly recognized as the end of an era. The Second Reform Act, which almost doubled the electorate, followed in 1867; and the Education Act, which opened the way for national elementary education, was passed in 1870. In 1871 appeared Charles Darwin's The Descent of Man, which reinforced the impact already made upon old scientific and religious ideas by his Origin of Species (1859). Walter Pater's Renaissance was published in 1873, the herald of 'aestheticism' in England. And finally, the 'great depression' which was to last a generation - threatened agriculture and industry from the mid 1870s.

Thomas Hardy, the novelist, claimed in The Return of the Native (1878) that concern had begun to show itself not only in the thoughts of contemporaries but even in their faces. 'People already feel that a man who lives without disturbing a curve of feature, or setting mark of mental concern upon himself, is too far from modern perceptiveness to be a modern type.' The steam-engine word 'pressure' began to be much used to describe disorder both in institutions and in individual lives. In 1875 appeared Social Pressure by Sir Arthur Helps, and W. R. Greg's article in the Contemporary Review for March on 'Life at High Pressure.' Greg quoted statistics from the British Medical Journal which showed how the number of deaths from heart disease among men aged between twenty and forty-five had risen from 0.553 per 1,000 per year in 1851-5 to 0.709 in 1866-70. The faces in Gustave Doré's famous drawings for London (1872) were certainly animated and urban, very different from the round and comfortable visage of traditional John Bull. In 1866 the editor of Punch asked his leading artist 'to modernize the John Bull he draws'.1 A more representative Englishman was now 'the man on the top of a Clapham omnibus'. But was this new town type less healthy in body and more volatile in temperament than old farmer Bull? England was changing and so perhaps were Englishmen, as the second half of Victoria's reign began.

1. R. G. G. Price, History of Punch (1957), pp. 107, 119.

Chapter 2

Economic Life

‘The full morning of our national prosperity’

1

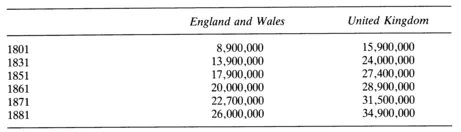

Statistics of population, occupation, and location revealed a society which was becoming extended, urbanized, and industrialized as never before. At the 1871 census the population of England taken by itself totalled almost 21,300,000 men, women, and children. The population of England and Wales taken together had grown more than two-and-a-half fold since the start of the century: The Preliminary Report upon the 1871 census remarked complacently how during Queen Victoria's 'happy reign' 5,900,000 people had been added to the total of her subjects, 'not by the seizure of neighbouring territories, but mainly the enterprise, industry, and virtue of her people'.

The industry of the Victorians in reproduction was certainly impressive:1

| Births per thousand | Deaths per thousand | |

|---|---|---|

| 1861-5 | 35.8 | 22.6 |

| 1866-70 | 35.7 | 22.6 |

| 1871-5 | 35.7 | 22.0 |

| 1876-80 | 35.4 | 20.8 |

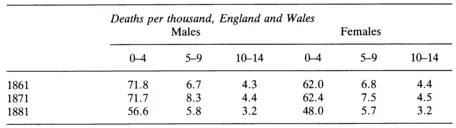

In 1871 births in England and Wales totalled 797,000, deaths 515,000. Concealed within the high overall death rates were even higher rates of infant and child mortality: The infections which were the greatest killers of Victorian infants and children showed no respect for social class. In 1856 Dean Tait of Carlisle lost five young daughters in one single scarlet fever epidemic. The sombre realities of Victorian life and death were forcefully illustrated in the Registrar-General's Annual Report for 1872, which contained a survey by Dr William Farr, Superintendent of the Statistical Department, entitled 'March of an English Generation through Life'. This survey showed what would happen to every million children born if their life experience proved to be the same in each age group as it had been for those same age groups during the 1860s. At ages 0-4 over a quarter (263,182) would die, chiefly from infectious diseases such as measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, and from pneumonia or bronchitis. 141,387 boys would die and 121,795 girls, to leave the sexes almost equal in numbers. 'Nearly every one of the 736,818 survivors has been attacked by one disease or another; some by several diseases in succession. There is one fact in their favour: the majority of zymotic diseases rarely recur.' Yet 34,309 would still die aged 5-9 - 8,743 from scarletina, 'the principal plague of this age'. This would leave 702,509 to enter puberty. Another 17,946 would die aged 10-14: 'the deaths are fewer than at any other age'. 684,563 would then enter the 15-19 age group, of whom 5,263 females and 3,811 males would die of consumption. Tight-lacing was suggested as a reason for the significant excess among girls. Within the 20-24 age group 'large numbers' would marry. There would be 28,705 deaths, 13,785 from consumption. 1,100 women would die in childbirth. 634,045 people would then reach their twenty-fifth birthday, 571,993 their thirty-fifth. 'The prime of life; two-thirds of the women are married; and now at its close is the mean of the period (33-34) when husbands become fathers, wives become mothers, the new generation is put forth.' 2,901 women would die in childbirth. Consumption would cause 27,134 deaths, more among women than among men. And at this age total deaths among women (31,460) would outnumber those among men (30,592).

Over the ages 35-44 deaths would total 69,078 (men 35,142, women 33,936). Consumption 'still predominates'. 'It is the age of fathers and mothers.' The original million would have been halved a few months after entering the 45-54 age group. At this stage there would be 81,800 deaths. 'The centres of life are the sources of death' - heart, lungs, liver, stomach. Cancer would take 4,583 lives. There would be equal numbers of men and women surviving at age 53; but from 55 the number of surviving women would be greater than that of men. 421,115 men and women would enter the 55-64 age group; only 309,029 would attain their sixty-fifth birthday. Over the ages 65-74 this number would be sharply cut to 161,124. At the end of the 75-84 range the total of survivors would be down to 38,565. A mere 2,153 would reach 95; 223 would attain 100, and the last would die at 108.

This survey was dealing in averages, and so could not reveal the many local variations in mortality rates. But elsewhere in the report it was noted how in Liverpool - parts of which were grossly overcrowded - not even a quarter but nearly one-half of all children died before reaching the age of 5. Only one in four of Liverpudlians reached the age of 45. 'Every great city has in it a bit of Liverpool.'

2

In terms of numbers Victorian society was dominated by children and young people. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s the average age of the population stayed constant at 26.4 years. In 1871 out of a total population of just over 22,700,000, almost 10,400,000 were aged under 20; less than a quarter (4,400,000) were aged over 45. The predominant youthfulness of the population meant that in 1871 (even leaving aside widows and widowers) as many as 61.3 per cent of males and 58.7 per cent of females were unmarried. The marriage rate - corrected for the proportion of marriageable persons in the population - fluctuated through most of the 1860s and 1870s about 18.0-19.0 per thousand, with a peak of almost 21.0 in the prosperous year of 1873.2 By the 1860s rising costs or aspirations of living were often said to be leading to more postponement of marriage by middle-class men. But they had always tended to marry late. In 1871 the mean age of marriage among manual workers stood about 24.0 years, whereas among shopkeepers and farmers it was 27.0 and among professional men and managers it reached nearly 30.0. The mean age of marriage for brides varied much less between classes than for bridegrooms, ranging between a working class mean of 22.0 to a middle-class mean about 25.0.3

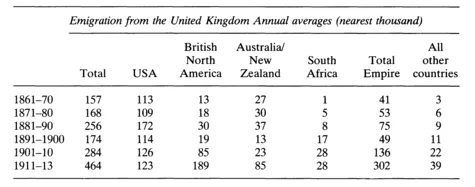

In most years 'swarms of emigrants' (in the words of the Registrar-General) were drawn off overseas, chiefly to the United States and to the colonies. Only approximate emigration statistics can be calculated; but it has been estimated that England lost 1,355,000 people by emigration over the period 1871-1911, roughly 10 per cent of her natural increase.4 Nine out of ten of these emigrants were aged under 40:

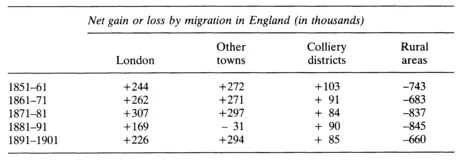

Though large numbers were moving overseas, much greater numbers were migrating within the United Kingdom, especially from the countryside to work in the towns.5 Except in the 1880s - when overseas emigration was particularly heavy the towns absorbed at least half a million migrants per decade during the second half of the nineteenth century:6 The General Report upon the 1871 census had explained how the new mobility offered by the railways and by improved roads had encouraged 'the flow of people'. Nevertheless, apart from the Irish, most migrants moved only short distances. They did so, however, within a ripple effect, as an important paper on 'The Laws of Migration' explained to the Statistical Society in 1885. The inhabitants of the country immediately surrounding a town of rapid growth flock into it; the gaps thus left in the rural population are filled up by migrants from more remote districts, until the attractive force of one of our rapidly growing cities makes its influence felt, step by step, to the most remote corner of the kingdom.'

Women were even more mobile than men. Domestic service attracted them in large numbers to the towns, but they also migrated for factory and shop work. 'The workshop is a formidable rival of the kitchen.' The magnetism of the provincial towns tended to fluctuate as their trade expanded or stagnated: the pull of London was both the strongest and the steadiest. Rather more than one in three of London's inhabitants had been born outside the c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introductory note

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- PART ONE: THE VICTORIAN TURNING POINT, 1868-1880

- PART TWO: FIN DE SIÈCLE, 1880-1900

- PART THREE: EDWARDIAN ENGLAND, 1901-1914

- Further reading

- Index