![]()

Section III

Plants and Crops Responses: Physiology, Cellular and Molecular Biology, Microbiological Aspects, and Whole Plant Responses under Salt, Drought, Heat, Cold Temperature, Light, Nutrients, and Other Stressful Conditions

![]()

13 | Responses of Photosynthetic Apparatus to Salt Stress |

Structure, Function, and Protection

M. Stefanov , A.K. Biswal , M. Misra , A. N. Misra , and E.L. Apostolova

CONTENTS

13.1 Introduction

13.2 Organization of the Photosynthetic Apparatus

13.3 Effects of Salt Stress on Plants

13.3.1 Plant Growth, Development, and Yields

13.3.2 Photosynthetic Pigments

13.3.3 Lipid Composition

13.3.4 Chloroplasts and Thylakoid Membranes

13.3.4.1 Structure

13.3.4.2 Function

13.4 Defense Mechanism in Plants against Salt Stress

13.4.1 Antioxidative Defense System

13.4.2 Xanthophyll Cycle

13.4.3 Accumulation of Osmolytes

13.5 Conclusions

Acknowledgment

Bibliography

13.1 Introduction

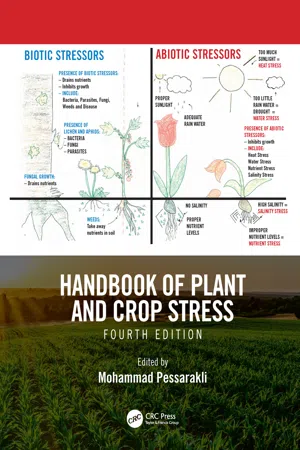

In recent years, extensive studies have been conducted to understand the effects and mechanism of tolerance of plants to environmental stress. The external abiotic and biotic factors that limit the rate of photosynthesis and reduce the ability of plants to convert energy to biomass, thereby reducing the growth development and ultimate yield, are defined as stress (Parihar et al., 2015). Plants are continuously exposed to a broad range of environmental stress factors, such as salinity (salt stress), drought, UV radiation, light, flooding, and temperature, which alter their physiological and biochemical processes (Misra et al., 2001a, 2001b, 2001c, 2002, 2012a, 2012b, 2014; Chaitanya et al., 2014; Suzuki et al., 2014; Misra and Misra, 2018a, 2018b). Decreased yields, as a result of the action of abiotic stress factors, the increasing human population, and the reduction in agricultural land, are leading to alarming predictions of depletion of food resources, and people are looking for new strategies that can guarantee the supply of food (Misra et al., 2002; Rasool et al., 2013; Shahbaz and Ashraf, 2013; Shrivastava and Kumar, 2015). The beginning of the twenty-first century is marked by global scarcity of water resources, environmental pollution, and increased salinization of soil and water. High salinity levels can lead to changes in soil properties, which negatively affect the environment, soil fertility, and agricultural production and result in serious harm to human health (Misra et al., 1995, 2001d; Brevik et al., 2015; Daliakopoulos et al., 2016; Hachicha et al., 2018). Furthermore, soil salinization leads to the alteration or even disruption of the earth’s natural biological, biochemical, hydrological, and erosional cycles (Daliakopoulos et al., 2016).

Nearly 10% of the world’s irrigated area (34.19 × 106 ha) (Mateo-Sagasta and Burke, 2011) and about 7–8% of the total land area (932.2 × 106 ha) (Daliakopoulos et al., 2016) is affected by salinization. It has been suggested that more than 50% of agricultural land will be affected by salinization by 2050, which will affect the food needs of the world’s population (Rasool et al., 2013; Fahad et al., 2015; Shrivastava and Kumar, 2015). Salinity limits plant growth and development, causes physiological and metabolic imbalance in plants, and thus, decreases crop yields (Misra et al., 1990, 1995, 1996, 1997a, 2001a, 2001b; Krasensky and Jonak, 2012; Chaitanya et al., 2014). Salinization leads to destruction of enzyme structure, membrane integrity, and cell metabolism (Shokri-Garelo and Noparvar, 2018; Tanveer et al., 2018), which negatively affects germination, growth, flowering, photosynthesis, and respiration (Misra et al., 1990, 1995, 1996, 1997a, 2001a, 2001b; Ghosh et al., 2016; Stefanov et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c; Wungrampha et al., 2018).

The deleterious effects of salinization on plants are accompanied by osmotic stress, nutritional imbalance (Attia et al., 2011), ionic stress (Misra et al., 1990, 2001a, 2002; Munns and Tester, 2008), or a combination of these factors (Hapani and Marjadi, 2015). First, plants are subjected to a quick shock of osmotic stress, resulting in a physiological drought condition. Second, ions such as Na+ and Cl− cause ionic imbalance and further hinder the uptake of minerals such as K+, Ca2+, and Mn2+ (Misra et al., 2002; Ahmadizadeh et al., 2016; Nongpiur et al., 2016).

This chapter is focused on the effects of salt stress on the light reactions of photosynthesis and some defense mechanisms, such as osmoprotectants and the antioxidant defense system.

13.2 Organization of the Photosynthetic Apparatus

The light reactions of photosynthesis in oxygenic organisms such as higher plants, green algae, and cyanobacteria are mediated by four multi-subunit protein complexes: photosystem I (PSI), photosystem II (PSII), cytochrome b6f complex, and ATPase (Joshi et al., 2013; Apostolova and Misra, 2014). These complexes are embedded in the thylakoid membrane of chloroplasts and carry out the conversion of light energy into usable chemical energy (Nevo et al., 2012). Both photosystems (PSII and PSI) are membrane-associated supercomplexes composed of a core complex and a peripheral antenna system, which is important for light harvesting. The stability of the photosynthetic apparatus is very important for the efficiency of photosynthesis (Karapetyan, 2004).

The light-driven reaction carried out in the PSII complex leads to the photolysis of water, which releases oxygen, electrons, and protons. The function of PSII is associated with charge separation across the thylakoid membranes (Misra, 2001b, 2001c; Govindjee, 2006; Joshi et al., 2013; Apostolova and Misra, 2014; Misra, 2018b), and this photosystem works together with the other main protein complexes, such as PSI and cytochrome b6f complex, to perform the primary light reactions (Kouřil et al., 2012). The PSII supercomplex is composed of a PSII core and an outer light-harvesting complex system. The PSII core complex contains 20 different subunits, pigments, and lipids, many of which are evolutionarily conserved between cyanobacteria and plants, while the highly diverse antenna complex is found in the periphery of PSII (Watanade et al., 2009; Croce and Amerongen, 2011). The PSII reaction center is composed of the D1 and D2 polypeptide heterodimer, where the primary charge separation occurs. Closely associated with the reaction center are the inner antenna proteins CP43 and CP47 and a range of small hydrophobic polypeptides, which together comprise the PSII core complex (Büchel et al., 1999). To this complex belong the polypeptides of the oxygen-evolving complex (16, 23, and 33 kDa), which are luminal extrinsic subunits associated with oxygen evolution (Stoylova et al., 2000). The 33 kDa peripheral protein is called the Mn-stabilizing protein; it directly participates in the oxidation of water and also plays a role in the binding of Ca2+ and Cl− ions to the Mn cluster (Semchonok, 2016). There is evidence that removal of CP43 affects the photoreduction of QA; i.e., this protein stabilizes the QA binding site via the D2 subunit. In addition, CP47 interacts with three external PSII proteins (PsbO, P, and Q), which optimize the oxygen-evolving process, and thus, helps them to better bind to the PSII complex (Luciriski and Jackowski, 2006). Büchel et al. (1999) have shown that CP43 is not required for the water oxidase activity of PSII, although mutational studies demonstrate its involvement in normal PSII assembly and function in vivo. The authors suggest that CP47 plays an important role in the assembly and the function of the Mn clusters of the oxygen evolving complex. Recent investigations reveal that CP43 participates in the binding of the Mn4Ca cluster and peripheral proteins of the oxygen evolving complex, and the detachment of this pigment–protein complex is responsible for the changes in the donor side of PSII (Laczkó-Dobos et al., 2008).

PSI (or plastocyanine:ferredoxin oxidoreductase) is a multisubunit pigment–protein complex, which catalyzes the light-dependent electron transport from the plastocyanine to the ferredoxin (Semchonok, 2016). This photosystem contains approximately 13 protein subunits, 96 chlorophyll molecules, 22 carotenoids, three [4Fe-4S] clusters, two philoquinones, and four lipid molecules (Ozakca, 2013; Mamedov et al., 2015). The core complex of PSI is composed of a heterodimer (PsaA and PsaB), to which a wide range of cofactors related to the light capture and the light harvesting as well as cofactors participating in the electron transport are linked (Jensen et al., 2007; Caffarri et al., 2014).

It has been found that PSII and PSI are heterogeneous in their structure and functions. On the basis of the antenna size, PSII has been classified into three forms (PSIIα, PSIIβ, and PSIIγ centers) (Mehta et al., 2010). The major part of the PSII complexes (PS2α) are located in the appressed grana regions of thylakoid membranes, while a smaller fraction of the PSII centers (PSIIβ and PSIIγ centers) is located in the stromal lamellae (Jajoo, 2014). PSIIγ has the smallest antenna system and at the same time has the longest lifetime in comparison with PSIIα and PSIIβ (Jajoo, 2014). The PSIIβ and PSIIγ centers are characterized by delayed photosynthetic electron transport due to the small and weak electron donor systems (Jajoo, 2014). The PSII centers possess heterogeneity depending on their ability to reduce the ...