![]()

1

Introduction

iStock

Signpost at Land’s End (Cornwall, UK) and the sea’s beginning

The state of the ocean environment

The global ocean is ailing.

With each passing day comes news of further degradation, continued overexploitation, heightened conflict, the ravages of climate change and even unanticipated environmental issues concerning our ocean and coasts. And while there are small-scale success stories out there, the scramble is on for a new paradigm and new way of doing business – the ocean management business.

The continuing decline in the health of the global ocean and its coasts comes with risk to human well-being everywhere. While coastal and marine ecosystems are dynamic, in many cases they are now undergoing more rapid change than at any time in their history (Millennium Ecosystems Assessment (MEA), 2005). Transformations have been physical, as in the dredging of waterways, infilling of wetlands and construction of ports, resorts and housing developments, and they have been biological, as has occurred with declines in abundances of marine organisms such as sea turtles, marine mammals, seabirds, fish and marine invertebrates (Halpern et al., 2008; Worm et al., 2006). The dynamics of sediment transport and erosion-deposition have been altered by land and freshwater use in watersheds; the resulting changes in hydrology have greatly altered coastal dynamics. These impacts, together with chronic degradation resulting from land-based and marine pollution, have caused significant ecological changes and an overall decline in many ecosystem services (MEA, 2005).

Human pressures on coastal resources compromise the delivery of many ecosystem services crucial to the well-being of coastal peoples and national economies. Stocks of coastal fishery species, like most offshore fisheries, have been severely depleted. In the latest estimate by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, over 80 per cent of the world’s commercially fished stocks were found to be at capacity or overexploited (FAO, 2009). A recent review of fisheries management across the globe finds that it is difficult to identify even a single coastal nation that is not under the influence of overcapacity of fishing fleets or perverse subsidies for fisheries development. And while there is much disagreement about whether fisheries management can keep abreast of the increasing pressures to supply fisheries products for consumption, to support agriculture and even to provide fertilizers for landscaping, even conservative fisheries managers largely agree that better management is needed (Worm et al., 2009).

Depletions in fisheries stocks not only cause scarcity in resource availability (as well as substantial wealth inequities in many parts of the world), but also change the productivity of coastal and marine food webs, impacting the delivery of other services important to mankind (Dayton et al., 1995; 2002). Such services include providing coastal developments protection from erosion and storm damage, and increasing the value of recreational and tourist experiences, among others.

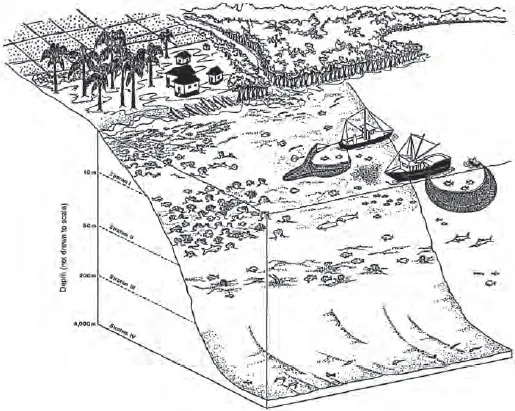

Biological transformations are also coupled to physical transformations of the coastal zone. Habitat alteration continues to be pervasive in the coastal zone, and degradation of habitats both inside and outside these systems contributes to impaired ecological functioning. Similarly, human activities far inland, such as agriculture and forestry, impact coastal ecosystems when freshwater is diverted from estuaries, and when land-based pollutants enter coastal waters (nearly 80 per cent of the pollutant load reaching the oceans comes from terrestrial sources). These chemical transformations impact the viability of coastal systems and their ability to deliver services. Thus, changes to ecosystems and services occur as a function of land use, freshwater use and activities at sea, even though these land-freshwater-marine linkages are often overlooked (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Schematic of coastal system

Source: Daniel Pauly

Larger forces are also at play. Coastal areas are physically vulnerable: many areas are now experiencing increasing flooding, accelerated erosion and seawater intrusion into freshwater, and these changes are expected to be exacerbated by climate change in the future (IPCC, 2003). Such vulnerabilities are currently acute in low-lying mid-latitude areas, but both low-latitude areas and polar coastlines are becoming increasingly vulnerable to climate change impacts. Coral reefs and atolls, salt marshes and mangrove forests, and seagrasses will likely continue to be impacted by future sea-level rise, warming oceans and changes in storm frequency and intensity (Sale, 2008). Even open ocean systems are under severe threat from climate change impacts, including the ocean acidification and oxygen depletion that occurs as ocean waters warm (Brierley and Kingsford, 2009). For instance, some models predict that oxygen levels in the seas will decline 6 per cent for every 1 degree increase in temperature, leading to accelerated growth in ‘dead zones’ across the globe. These areas of low or no oxygen cannot continue to support marine life, and the expansion of these dead zones will likely have a profound effect not only on marine fisheries but on human health as well.

At the same time, the incidence of disease and emergence of new pathogens is on the rise, and in many cases will have significant human health consequences (NRC, 1999; Rose et al., 2001). Episodes of harmful algal blooms are increasing in frequency and intensity, affecting both the resource base and humans living in coastal areas more directly (Burke et al., 2001; Epstein and Jenkinson, 1993). Effective measures to address declines in coastal health and productivity remain few and far between, and are often too little, too late. Restoration of coastal habitats, although practised, is generally so expensive that is remains a possibility only on the small scale or in highly developed countries. Education about these issues is lacking, and therefore this crisis may rest in large part on our inability to communicate what is happening and why.

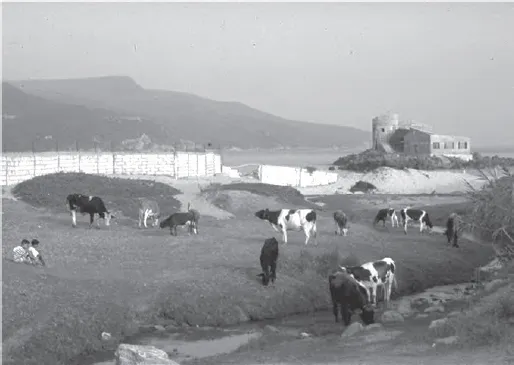

Dependence on coastal zones is increasing around the world, even as costs of rehabilitation and restoration of degraded coastal ecosystems are on the rise. In part this is because population growth overall is coupled with increased degradation of terrestrial areas (fallow agricultural lands, reduced availability of freshwater, desertification and armed conflict contributing to decreased suitability of inland areas for human use). Resident populations of humans in coastal areas are growing, but so are in-migrant (internal migrant) and tourist populations (Burke et al., 2001), while wealth inequities rise in part from the tourism industry and private landowners decreasing access to coastal regions and resources for a growing number of humans (Creel, 2003; McCay, 2008). Nonetheless, local communities and industries continue to exploit coastal resources of all kinds, including fisheries resources; timber, fuelwood and construction material; oil, natural gas, strategic minerals, sand and other nonliving natural resources; and genetic resources. In addition, people increasingly use ocean space for shipping, security zones, renewable energy, recreation, aquaculture and habitation. The photo in Figure 1.2 shows a small stretch of coastline in Algeria, just one example of these disparate and potentially conflicting uses of coastal and marine ecosystems; these and other uses are the focus of zoning initiatives.

Coastal zones provide far-reaching and diverse job opportunities, and in many countries represent the geographic areas having the greatest contribution to GDP or GNP. Income generation and human well-being, as measured by various economic and social parameters, are currently higher on the coasts than inland across the globe.

Despite their value to humans, coastal and marine systems and the services they provide are becoming increasingly vulnerable. Although the thin strip of coastal land at the continental margins and within islands accounts for only 5 per cent of the earth’s land area, nearly 40 per cent of the global population lives in the coastal zone (CIESIN, 2003, using 2000 census data). Population density in coastal areas is close to 100 people per km2 compared to inland densities of 38 people per km2 in 2000 (MEA, 2005). Though many earlier estimates of coastal populations have presented higher figures (in some cases, nearly 70 per cent of the world population was cited as living within the coastal zone), previous estimates used much more generous geographic definitions of the coastal area and may be misleading (Tibbetts, 2002).

Figure 1.2 Algerian beach scene exemplifying some potentially conflicting uses of the marine and coastal environment

Source: T. Agardy

In general, management of coastal resources and human impacts on these areas is insufficient or ineffective, leading to conflict, decreases in services and decreased resilience of natural systems to changing environmental conditions. Inadequate fisheries management persists, often because decision-makers are unaware when marine resource management is ineffective, while coastal zone management rarely addresses problems of land-based sources of pollution and degradation (Kay and Alder, 2005). Funds are rarely available to support management interventions over the long term, resources become overexploited and then unavailable, and conflicts increase.

A new paradigm, or at the very least, a substantial ramping up of truly effective management, is badly needed. It is unlikely that old management tools and approaches will be sufficient to meet these ever-increasing, and sometimes newly emerging, challenges. But what is the top priority for a better ocean future?

Like many other assessments and publications before and since, the 2006 National Academy of Sciences book entitled Increasing Capacity Building for Stewardship of Oceans and Coasts: A Priority for the 21st Century (NRC, 2006) identified fragmentation of management as one of the most pervasive and prominent obstacles to effective marine management. Ocean zoning by its very nature overcomes fragmentation – obligating the managers of all the various sectors using marine resources and ocean space to think strategically and plan for sustainable use.

In facing a climate-changed and challenged future, which will have over 8 billion human inhabitants to house and feed, getting the management right is imperative. Only healthy and well-functioning ecosystems will be able to adapt to a changing world and continue to provide the goods and services that maintain life on earth. And only regulations and rules that are derived through the active participation of those who will be affected will be accepted, with a minimum of conflict and risk to national security. The strategic planning and adaptability inherent in zoning may be the single most important weapon in our armoury to achieve effective, efficient and equitable management of resources – a battle we have been waging, and losing, for quite some time now.

Ocean zoning to meet ocean management challenges

Zoning is a set of regulatory measures used to implement marine spatial plans – akin to land-use plans – that specify allowable uses in all areas of the target ecosystem(s). Different zones accommodate different uses, or different levels of use. As in municipal zoning, regulations address prohibitions or permitted uses, or both. All zoning plans are portrayed on maps, since the regulations are always area-based.

Ocean zoning has been repeatedly brought up as having much potential, as managers have struggled to slow or halt coastal degradation and overexploitation of marine resources. More often, government agencies, conservationists and planners have skirted ocean zoning without actually invoking the term. Instead, they speak of comprehensive ocean planning, marine spatial management, place-based conservation and the like. Although the ocean zoning concept itself is just a natural extension of what we do on land, for some reason it is feared. Thus comprehensive ocean zoning efforts have largely remained in the realm of theory, in part because of this fear.

Marine spatial management really began with indigenous coastal and island cultures and their marine tenure and taboo practices, and then became more widespread (and legitimate, in the eyes of some) when formal marine protected areas started to be established. Then, when practitioners realized that few marine protected areas were meeting broad scale conservation objectives, and that an ad hoc, one-off approach would not lead to effective large-scale conservation (Allison et al., 1998), the concept of marine protected area networks emerged as a way to strategically plan marine protected areas with the hope that the whole would be greater than the sum of its parts (Roberts et al., 2003). A system or network that links these protected areas has a dual nature: connecting physical sites deemed ecologically critical (ecological networks), and linking people and institutions in order to make effective conservation possible (human networks). Networks or systems of marine protected areas have great advantages in that they spread the costs of habitat protection across a wider array of user groups and communities while providing benefits to all.

While networks are a step in the right direction, even strategically planned networks do not necessarily lead to effective marine conservation at the largest scale (Christie et al., 2002). Recognizing that more was needed than marine protected area networks, planners began to explore the concept of marine corridors and broader spatial management. Essentially, a corridor uses a marine protected area network as a starting point and determines through conservation policy analysis which threats to marine ecology and biodiversity cannot be addressed through a spatial management scheme. The connections between the various marine protected areas in a network are maintained by policy initiatives or management reform in areas outside the protected areas. In such corridors (or regional planning initiatives by any other name) marine policies are directed not at the fixed benthic and marine habitat that typically is the target for protected area conservation, but rather at the water quality in the water column and the condition of marine organisms within it. Corridor concepts provide a way for planners and decision-makers to think about the broader ocean context in which protected areas sit and to develop conservation interventions that complement spatial management techniques like marine protected areas and networks. Corridors and regional planning efforts are few and far between, however, and most marine conservation still occurs through a piecemeal, almost desperate, process without large-scale visioning and coordinated strategic action.

But in the minds of many, a real quantum leap in conservation effectiveness occurs when planners scale up from marine protected area (MPA) networks and corridor concepts to full-scale ocean zoning (Agardy, 2007; 2009). Ocean zoning provides many benefits over smaller scale interventions: it can help overcome the shortcomings of MPAs and MPA networks in moving us towards sustainability; it is based on a recognition of the relative ecological importance and environmental vulnerabilities of different areas; it allows harmonization with terrestrial land-use planning; it can help better articulate private sector roles and responsibilities and maximize private sector investment by allowing free market principles to work in concert with government protections; and it moves us away from the terrestrial focus of traditional integrated coastal management efforts to more effective, integrated and holistic environmental management that fully includes uses of, and impacts on, the oceans.

Ocean zoning is a planning tool that comes straight out of the land-use planning methodologies developed in the 1970s and used at the municipal, county, state, regional and national levels. As on land, it allows a strategic allocation of uses based on a determination of an area’s suitability for those uses, and reduction of user conflicts by separating incompatible activities. There are genera...