- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

It is surprising how much of everyday conversation consists of repetitive expressions such as 'thank you', 'sorry', would you mind?' and their many variants. However commonplace they may be, they do have important functions in communication.

This thorough study draws upon original data from the London-Lund Corpus of Spoken English to provide a discoursal and pragmatic account of the more common expressions found in conversational routines, such as apologising, thanking, requesting and offering.

The routines studied in this book range from conventionalized or idiomatized phrases to those which can be generated by grammar. Examples have been taken from face-to-face conversations, radio discussions and telephone conversations, and transcription has been based upon the prosodic system of Crystal (1989).

An extensive introduction provides the theory and methodology for the book and discusses the criteria for fixedness, grammatical analysis, and pragmatic functions of conversational routines which are later applied to the phrases. Following chapters deal specifically with phrases for thanking, apologising, indirect requests, and discourse-organising markers for conversational routines, on the basis of empirical investigation of the data from the London-Lund Corpus of Spoken English.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conversational Routines in English by Karin Aijmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

1.1 Aim and scope of the present study

Many grammatical structures have a stable form in all the contexts in which they occur. One of the first scholars to draw attention to this was Jespersen:

Some things in language – in any language – are of the formula character; that is to say, no one can change anything in them. A phrase like ‘How do you do?’ is entirely different from such a phrase as ‘I gave the boy a lump of sugar.’ In the former everything is fixed: you cannot even change the stress saying ‘How do you do?’ or make a pause between the words. … It is the same with ‘Good morning!,’ ‘Thank you,’ ‘Beg your pardon,’ and other similar expressions. One may indeed analyze such a formula and show that it consists of several words, but it is felt and handled as a unit, which may often mean something quite different from the meaning of the component words taken separately. (Jespersen 1968 (1924): 18)

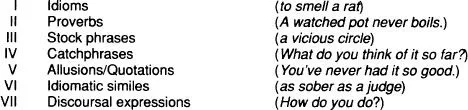

Lately a great deal of attention has been paid to expressions such as how do you do, I am sorry, hello, etc which are closely bound to a special function or communication situation (see also Carter 1987: 59).1 They are variously called bound utterances’ (Fónagy 1982:4 – ‘énoncés liés’), ‘situation formulas’ (Yorio 1980: 436), ‘discoursal expressions’ (Alexander 1984; see Figure 1.1) or ‘conversational routines’ (Coulmas 1981a: 2). The aim of the investigation undertaken in this work is to examine the properties of such expressions, which will here be called conversational routines.

In the past, fixed or formulaic expressions have, above all, been studied because of their importance for language acquisition (see section 1.4). Recently, there has been a greater interest in studying formulas in their own right from a linguistic and pragmatic perspective (see Bahns et al. 1986). This group is not homogeneous, but classes of fixed expressions can be distinguished on the basis of the degree of fixedness, institutionalization, situational dependence, syntactic form, etc (see Coulmas 1979; Lüger 1983). As a result there are idioms, clichés, proverbs, allusions, routines, etc (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Types of fixed expressions (Simplified after Alexander 1984:129; see Carter 1987: 60)

Conversational routines or discoursal expressions include a variety of phrases which are frequent in spoken language such as swear words (bloody hell), exclamations (oh dear), greetings (good morning), polite responses (thank you, I’m sorry), discourse-organizing formulas of different kinds (frankly speaking, to be brief) and ‘small talk’ (what a nice day).2

Conversational routines are analysed semantically in terms of the situation in which they are used. They can be grouped into several classes. One group consists of formulaic speech acts such as thanking, apologizing, requesting, offering, greeting, complimenting, which serve as more or less automatic responses to recurrent features of the communication situation. This class comprises both direct and indirect speech acts, simple speech acts and (routinized) patterns of speech acts.

A second large group of routines is characterized by their discourse-organizing functions rather than by their association with the social context. They are either ‘connectives’ contributing to the cohesion of the discourse or ‘conversational gambits’ with the function of opening the conversation (Alexander 1984:129). They can, for example, facilitate the transition to something new in the discourse, signal a digression and organize different aspects of the topic. As will be shown in Chapter 5, an account of discourse markers could be given in terms of whether they point backwards or forwards in the discourse context, are oriented to the speaker or hearer, etc.

A third group of conversational routines, which will not be dealt with in this work, consists of routines which express the speaker’s attitudes or emotions (‘attitudinal routines’).

In the linguistic literature the discussion has mainly concerned idioms, i.e. phrases whose meaning is not identical with the sum of their constituent parts (e.g. red herring, kick the bucket) (see, for example, Makkai 1972), although also proverbs and clichés have been the subject of interesting studies (see Norrick 1985 on proverbs). The current interest in conversational routines can be seen as an outcome of their idiomatic nature and their importance for communicative competence. They have become a major area of pragmatic research and have had an effect on our views on language acquisition, language performance and foreign language teaching.

When Uriel Weinreich delivered a number of lectures on the problems in the analysis of idioms in the middle of the 1960s (published in Weinreich 1980), he began by apologizing for taking up so unfashionable a topic. Since then, the pendulum has swung in the direction of making the study of idiomaticity fashionable, and bold claims have been made with regard to the overall importance of idiomaticity and formulaicity in language. One can distinguish two trends in this development. On the one hand, lexicographers have started to compile special dictionaries of fixed expressions (see, for example, The Oxford dictionary of current idiomatic English, The BBI combinatory dictionary of English). On the other hand, large-scale investigations of collocational phenomena have been undertaken which indicate that lexical patterning is indeed pervasive in both speech and writing (see Altenberg and Eeg-Olofsson 1990; Kennedy 1990; Kjellmer 1991; Sinclair 1987).

As I see it, there is no definite cut-off point between fixed or completely conventionalized ways of expressing functions and the use of less stable or ‘free’ utterances although the emphasis in my presentation will be on devices which are fixed according to some or several criteria. The approach in this work is similar to that in communicative language teaching, as the starting-point is functional, and I am interested in the realization of certain common and useful communicative functions. Conversational routines can, however, be multi-functional, and the derived functions will also be considered in this work. Thank you will, for example, be analysed both as a gratitude expression and as a closing signal.

The study is organized as follows. Chapter 1 discusses the theoretical framework within which conversational routines will be described formally and pragmatically. Within this theory a psychological and social explanation for conversational routines is proposed, conversational routines are defined, and aspects of their use and linguistic realization are discussed (frequency, fixedness, function, grammatical and semantic analysis, etc). Finally, a model for describing conversational routines grammatically, semantically and pragmatically is suggested. In Chapters 2 and 3, I describe different types of routinized speech acts in the London-Lund Corpus of Spoken English. Chapter 2 deals with speech acts with the function of thanking, and Chapter 3 with apologizing. Chapter 4 discusses routinized requests and offers which are usually expressed indirectly. Chapter 5 is concerned with routines which have a discourse-strategic and cohesive function.

1.2 Material and method

The present study is based primarily on the London-Lund Corpus of Spoken English. The use of a corpus is a fairly new method for studying speech acts and other routines, although a number of studies of spoken English have been carried out on the basis of the London-Lund Corpus (see Svartvik 1990). The corpus approach needs to be discussed and related to other approaches.

The usual method of collecting spoken data, consisting of speech acts and other routines, is role plays enacted by native speakers (e.g. House and Kasper 1981; Cohen and Olshtain 1981; Eisenstein and Bodman 1986). The advantages of this method are that the analyst can choose what situations he wants to study, and that larger quantities of data can be collected. Many sociolinguists, on the other hand, have emphasized the importance of authentic data and ethnographic observation and have collected their own data (e.g. Manes and Wolfson 1981; Ervin-Tripp 1976; Holmes 1990).

The most extensive study of speech acts so far is the Cross-Cultural Speech Act Realization Project (CCSARP) (Blum-Kulka 1989: 47). In this project requests and apologies were examined in a large number of languages by testing a number of informants. The cross-linguistic data were elicited by means of a written discourse-completion test consisting of scripted dialogues representing different situations in which the informants were expected either to apologize or ask for something. It is obvious that data which have been extracted experimentally have certain methodological advantages, as these can be contrasted in different situations, media, cultures and languages. As stressed by Rintell and Mitchell (1989), elicited data must, however, be analysed with care. When they compared different methods, they found that the speech acts extracted by means of the discourse-completion test used in the CCSARP project tended to be quite long in comparison with role-play data.

Perhaps it is a sign of the novelty of the study of spoken language that there has been much discussion of methodological issues such as the authenticity of the spoken data collected by role play (see Holmes 1990: 164; Haggo and Kuiper 1983: 536). Another issue is the use of corpora as a methodology for pursuing linguistic research on spoken English. Text corpora are especially valuable because they provide information about facts which are difficult to study by means of introspection, such as the frequencies of linguistic elements in different genres and subgenres and their social and contextual constraints (see Leech 1992: 110; Svartvik 1992: 9).

The investigation of frequencies can also throw some light on language competence. As Weinreich points out, ‘for an arbitrary sentence, it is clearly not part of a speaker’s competence to know whether he has heard it before or to know how frequent it is’ (1980: 255). On the other hand, it can be argued that the frequencies of linguistic routines are as important as their syntactic, semantic and pragmatic properties and that it is part of the speaker’s competence to know how frequent they are.

In a wider perspective, the methods of corpus linguistics can be combined with different linguistic theories and approaches. Quantitative methods and corpora have been successful in studying phenomena like gradience and ‘stereotypes’ in the area of modality (Leech and Coates 1980; see also Karlsson 1983a on prototypes in grammatical description) as well as grammaticalization (see Mair 1994; Thompson and Mulac 1991).

Several methods can be used together, and introspection may well be the first step in a corpus study. As Kennedy (1990) has shown, introspection can be of help when one makes an inventory of the types which are available to express a particular function. In addition, introspection (besides the reading of secondary sources) is needed to suggest the factors or dimensions of the pragmatic situation determining the form that routines of a particular function can have. Some examples of contextual factors which are intuitively likely to have a determining influence on the form of speech acts are setting, social distance and power relations between the participants. Experimental methods, however, may be necessary to test the results of a corpus investigation.

The number of spoken corpora is limited, and the spoken corpora which are available are considerably smaller than the written ones. The (original) London-Lund Corpus of Spoken English (LLC), which provides the spoken m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: Thanking

- Chapter Three: Apologies

- Chapter Four: Requests and offers

- Chapter Five: Discourse markers as conversational routines

- References

- Index