![]()

Chapter 1

Recognizing Those Who Are Depressed

Richard Dayringer

Depression is not entirely uncommon among the great saints of the church. William Cowper, who wrote poems and hymns, was depressed. He was a parishioner and close friend of John Newton, the eighteenth-century sea captain who became a preacher and wrote the words of the hymn “Amazing Grace.” Well-educated, cultured, and affluent, Cowper became involved in lay ministry but was devastated by bouts of despair. One time Newton was called to Cowper’s home only to find that he had made an unsuccessful suicide attempt by cutting his throat. He was utterly convinced that God had rejected him. At another time when Cowper was suicidal, Newton brought him to his home and kept him under surveillance. For months Cowper insisted that God had marked him for eternal damnation. Newton formed prayer groups to pray for Cowper’s mental health. Finally, the gloom lifted and he became his normal self (Deal, 1974).

Surveys indicate that 20 million people–15 percent of all adults between the ages of 17 and 74–may suffer serious depression from time to time, and few of them receive help (Bielski and Friedel, 1977). This means that during any six-month period, as many as 10 million Americans find themselves sliding into the black hole of depression, powerless to stop their descent. Or, to put it another way, “The chance of someone who lives to age 70 contracting depression during his lifetime is now seven and eight-tenths percent for males and twenty percent for females” (Callan, 1979).

An international study found that depression is on the rise the world over. Researchers questioned over 39,000 people in nine countries. They found that in each successive generation, major depression began at an earlier age and affected a greater number of people. Several explanations were offered for rising depression: a doubling of the divorce rate, a decrease in the time available for parents to spend with their children, industrial substances released into the air, and the decline of religious faith (Weissman, 1992).

It has been estimated that the average physician, during a lifetime of practice, will have 14 patients who commit suicide. Perhaps as many as 10 percent see their physicians on the day of or just prior to their suicide.

Ancient people also had to deal with depression. The Bible charts the depressive symptoms of such men as Job, Moses, Elijah, David, and Jeremiah. Elijah, for example, (First Kings, Chapter 19) withdrew into hiding after the triumph over the 400 priests of Baal. He expressed low self-esteem, lost his appetite, slept a lot, and asked to die. Jesus may have suffered depression during the time of the temptation. He fasted, slept little, and was tempted to jump off the pinnacle of the Temple.

Shakespeare put a description of Hamlet’s depression into the mouth of Polonius:

He … a short tale to make,

Fell into sadness, then into a fast,

Thence to a watch, thence into a weakness,

Thence to a lightness, and by this declension,

Into the madness wherein he now raves

And all we mourn for.” (Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2)

Numerous studies have shown that, at any time, between 9 and 20 percent of the U.S. population have depressive symptoms. The figures are higher among women (11 to 24 percent) than men (6 to 16 percent) (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1988).

When mental health professionals speak of “clinical depression,” they are referring to the clinical depressive syndromes. This means that the person is so depressed as to have physiological symptoms. The following terms are also generally used synonymously: autonomous, endogenous, endogenomorphic, melancholia, or vital depression. These terms refer to a group of increasingly identifiable subtypes of depression based on specific sets of symptoms and associated factors. The benchmark for clinical depression, compared to normal sadness, depends on the intensity, severity, and duration of symptoms. Generally (except in the case of bereavement over the death of a loved one), if the depressed mood and associated symptoms last for more than two weeks, and if they are of sufficient intensity to interfere with ordinary daily activities, this is considered a clinical depressive syndrome.

Depressive disorders occur most often between the ages of 25 and 44, although it has been documented in children as young as age five. For depression to first appear after age 60 is less common. Most studies indicate that it strikes women almost twice as frequently as men.

In recent years, remarkable progress has been made in the classification, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. But paradoxically, even in light of these clinical advances, depression often goes unrecognized. So, undertreatment is a significant problem. Some specialists believe that fewer than one-third of those who have serious depressive disorders receive adequate treatment. Despite the distressing nature of this illness, there is good news: even in its most serious forms, depression usually responds well to modern treatment methods, and symptoms often can be relieved quickly–sometimes within weeks.

Depression affects people in different ways. However, there are two consistent symptoms that can be relied upon to diagnose depression: a loss of interest or pleasure in all or almost all usual activities (anhedonia), and a relatively persistent disturbance of mood (dysphoria).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, (DSM-IV), published by the American Psychiatric Association, is the system most widely used in this country by mental health professionals to diagnose and classify mental and emotional disorders.

According to DSM-IV (see Appendix I), five of the following nine symptoms must be present most of the day, nearly every day, during a two-week period for a diagnosis of major depression to be made:

1. Depressed mood, or irritable mood in children and adolescents;

2. Loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities;

3. Significant weight loss or gain (more than 5 percent of normal body weight) when not dieting;

4. Disturbances in sleep patterns, whether insomnia (difficulty falling asleep, early morning awakening, or waking in the middle of the night) or hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness);

5. Agitation or a generalized slowing of intentional bodily activity, known as psychomotor retardation;

6. Fatigue or loss of energy;

7. Feelings of worthlessness, or excessive or inappropriate guilt;

8. Diminished ability to think or concentrate;

9. Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, or a suicide attempt.

NOTE: One of the five required symptoms must be either depressed mood or loss of interest in or failure to derive pleasure from usual daily activities. The many characteristics of depression fall into four main categories: mood disturbances, behavioral disturbances, cognitive (thought) impairment, and physiological changes or bodily complaints.

Depressed church members may express their mood with statements such as: “I feel down in the dumps,” or some other colloquial equivalent. They may worry about their sinfulness and magnify past failings or feel that they have not been forgiven for wrongs. They may complain, “I am unable to feel any emotion,” or “Nothing interests me or satisfies me,” or “I just don’t care about anything anymore.” They may feel worthless, guilty, and negative about the world and the future. They may become irritable, easily annoyed, and openly display anger in church meetings.

Depressed persons demonstrate various behavioral disturbances. Facial features may reveal the most important clues, such as appearing unhappy or sad, looking older than their actual age, having a furrowed forehead and downcast eyes, maintaining a blank expression, and allowing the corners of the mouth often to be turned downward. In addition, they may frequently withdraw from others, including not attending worship services. They may neglect their personal hygiene or appearance. Crying episodes often accompany depression, particularly in its early stages. But as depression becomes more protracted or severe, many individuals become incapable of weeping, even though they say they want to do so. Their posture may become stooped, the pitch of their voice monotonous, and they may delay noticeably in responding to questions.

As a result of impaired cognitive functioning, depressed persons often find it difficult to concentrate. Thoughts are slowed and confused, and decision making becomes exceedingly difficult. Thoughts often are centered on the self with prominent themes of helplessness and hopelessness. When posed questions, a depressed individual typically responds, “I don’t know.” Thoughts of death (not just fear of dying) are common. Often such persons believe that they would be better off dead. There may be suicidal thoughts, with or without a specific plan, or suicide threats and attempts.

Various physical symptoms frequently accompany bouts of depression. Most clinicians regard insomnia, especially early morning awakening, as the hallmark symptom of depression. Other bodily signs of depression include: gastrointestinal disturbances (such as indigestion, constipation, or diarrhea), weight loss or gain, menstrual cycle disturbances, loss of sexual interest, itching, dry mouth, blurred vision, and excessive sweating.

However, not all depressed people initially admit to symptoms typically associated with depression. Rather, they may complain of more vague ailments, such as headaches, backaches, or chronic pain. Depression with atypical features has been labeled “masked depression” (Lesse, 1974) and even “smiling depression.”

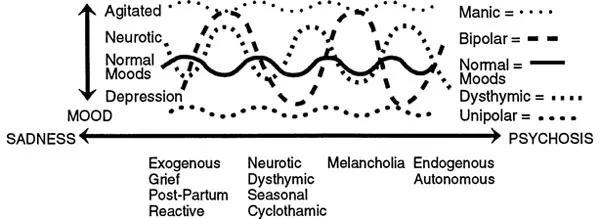

Depressive disorders come in different forms (see Figure 1.1). Some are episodic in nature, occurring just once or twice during a lifetime. Others are chronic, and they require some form of ongoing treatment to assist with disabling symptoms. Although different depressive disorders have many similar features, they often can be differentiated by certain characteristics, such as the type, severity, and duration of symptoms. Four of the most common types of depressive disorders are discussed below.

Manic Episode. The essential feature of a manic episode is a distinct period during which the predominant mood is either elevated, expansive, or irritable. These symptoms usually appear suddenly, with a rapid escalation over a few days. Associated symptoms include inflated self-esteem or grandiosity which may be delusional, decreased need for sleep, pressure of speech (speaking rapidly or hurriedly), flight of ideas, distractibility, psychomotor agitation, and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities. Manic speech is typically loud, rapid, and difficult to interrupt.

The euphoric mood is usually so cheerful as to be infectious for the uninvolved observer, but is recognized as excessive by those who know the person well. However, the predominant mood may be irritability, which may become most apparent when the person’s desires are thwarted.

Grandiosity is the over-estimation of one’s importance. Persons in a manic phase may give advice on matters about which they have no special knowledge, such as how to run a church or denomination. Despite lack of any particular talent, such a person may compose an anthem and insist that it be sung by the choir.

Flight of ideas is a nearly continuous flow of accelerated speech, with abrupt changes from topic to topic. Any external stimuli, even though irrelevant, may add to the person’s distractibility and tendency to jump from one subject to another.

People in a manic state have boundless energy, enthusiasm, and increased sociability. They may volunteer for numerous tasks at church and attempt to phone or visit prospects at all hours of the night. They usually do not recognize the intrusive, domineering, and demanding nature of these activities. They may contribute outrageously large gifts, drive recklessly, fight, or engage in unusual sexual behavior. Often these activities have a flamboyant quality, such as wearing strange garments or poorly applied makeup, or distributing money.

Bipolar Disorder. The most widely accepted subdivision of affective disorders is the distinction between bipolar and unipolar disorders, first proposed by Leonhard, Kerff, and Shulz in 1962. Some people experience recurrent cycles of both depression and mania. Because this condition involves emotions at different poles or extremes, it is termed “bipolar” disorder. It is frequently referred to as manic-depressive disorder and accounts for less than one-quarter of major depressive illnesses. In the depressive phase of a bipolar disorder, an individual may suffer from any of the sym...