![]()

Part I

Changing Environments, Changing Lives

![]()

1

Children’s Life Worlds: Adapting to Physical and Social Change

Since childhood is one of the few absolutely universal experiences, it is not surprising that people have an inward picture, even though it may never be articulated, of an ideal childhood. We may use it to reshape our own memories, we may try to recreate it for our own children. (Ward, 1978, p2)

Childhood

Childhood is generally accepted as being primarily a social construction. Its character is moulded by the norms of the society into which the child is born. These norms dictate matters as diverse as the influence that gender will have on the child’s ‘value’ and life opportunities, the likelihood of the child being part of a nuclear or extended family, the child’s spiritual dimensions, and even matters as pragmatic as what the child will eat for breakfast. Children are born into a society which will nurture them, sustain them and protect them, as well as neglect them, frustrate them, constrain them and provide them with their social and individual identity. Children possess their own character; but the society within which they are born and raised will impact upon how this character will develop and the extent to which children will be supported or obstructed in their desire and ability to become themselves. Adapting to and finding their way in society is one of the greatest of all accomplishments a child will make.

Adapting to society is one of the greatest accomplishments a child will make

How do children become socialized into society? Issues around the social development of children have intrigued those seeking to advance a philosophy of childhood. Early writers on this topic include luminaries such as Piaget (1954), Durkheim (1979), Erikson (1993) and Bowlby (1999, originally published in 1969), to more recent and, in some cases, lesser-known childhood thinkers such as Liedloff (1977), Postman (1994), Frones (1995), Spock and Needlman (2004), Stanley et al (2005), Donahoo (2007), Furedi (2008) and Leach (2009). What this disparate group has in common is the desire to understand and frame childhood. In the case of Piaget: to understand the conceptual and physical development of the child; in the case of Leach and Spock: to shape parental behaviours in a way that creates an ‘ideal’ family setting in which the child can develop.

While society is clearly important to children, it is only half the equation. As well as being shaped by their social world, children are shaped by their physical world: the places and spaces in which they grow up. This spatial world can be highly influential, as indicated in the following example where children may experience a similar family structure but live in spaces that impact very differently upon their life experiences. Two children are growing up in a two-parent, three-sibling family where the breadwinner works as a bus driver. One child lives with their family in a deprived, vandalized ‘sink estate’ in central London, the other on an established council (government housing) estate with low residential mobility in leafy Epsom, on London’s outer fringes. To take a second example, the experiences of a child growing up in an apartment above a shop in one of Toronto’s multicultural inner suburbs such as Agincourt with its large Chinese community would be quite different from a child growing up in an upmarket condominium in Toronto’s desirable South Beach suburb. These suburbs can be physically quite close; but the lifestyles and influences associated with them can be quite different. The same space can also be experienced very differently by children of differing abilities. An environment that may be welcoming and accessible to a physically able child may be experienced as challenging and isolating to a child with a disability (see Figure 1.1). Space matters: place, like society, shapes and influences behaviours, the spirit, sociability, opportunities, play, health, independence, physical and mental well-being, and even happiness. Yet, space has been given little attention in childhood literature; it has been taken as a given, allocated background status or reduced to relatively simplistic terms, such as healthy or unhealthy homes, environments which are good or bad for play, natural environments or sterile environments. Space acts as the nexus where society and place converge in the child’s life.

Figure 1.1 Children with disabilities can experience space differently

Source: Gretchen Good

Socially Determined Space

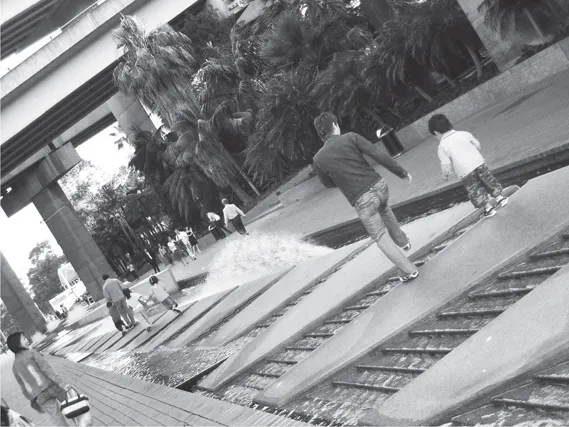

Space is complex: it varies not only at the larger scale between different cities, or parts of the city, but at the micro-scale, as in different parts of the street or home. These variations impact upon children in the most immediate ways. The design and culture of the street determines whether the child can cross a street to meet friends on the other side, while the height and design of the front garden fence will influence whether the child can see and interact with the ‘outside’ world or not. Space is also dynamic: its physical properties change. A quiet neighbourhood street can become a ‘rat run’ for commuting traffic, precluding street play and accessing neighbours on the other side. A neighbourhood that was once full of large upper middle-class homes can become a place of flux as family homes are subdivided into rentable rooms that house predominantly mobile populations. Not just buildings but the spaces around them change: a Victorian park can become a vandalized ‘no-go area’ characterized by minimal use, but with the right inputs can be revived into a safe community meeting and play place (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The redevelopment of Darling Harbour, Sydney, has created exciting, varied public spaces enjoyed by children and their families

Source: Claire Freeman

Tied up with physical change is social change. Where once it was seen as safe for children to be out and about at the park, use public transport and walk to school, some societies now see these same activities and journeys as dangerous and needing adult accompaniment. This was evident in the outcry directed at Lenore Skenazy (2009), author of Free-Range Kids. She wrote a piece for the New York Sun in which she described how her nine-year-old son used the New York subway alone. The article engendered some vehement responses in which many readers castigated her for her irresponsibility, with some going so far as to class her as ‘America’s worst mum’. Yet, if we look at the influential book by Colin Ward, Child in the City (Ward, 1978), published some 30 years ago there are several photographs showing exactly that: children using public transport without adults, some of the children being considerably younger than nine. Indeed, many children still take public transport alone to attend school. If you stand in the central business district (CBD) in Sydney, Australia, any school-day morning, multitudes of children from around age 11 can be seen emerging from buses and trains crossing the city to their usually private or selective schools – a seemingly acceptable undertaking. If Lenore Skenazy’s son had been dressed in a school uniform heading to a New York City centre school, would there have been the same outcry? Would groups of 11-year-olds taking the train to spend the day hanging about in Sydney’s CBD be as accepted as their school-uniform-wearing mid-week counterparts? We’d guess not: same journey, same geographic destination, but different societal associations. Furthermore, would those same school-going 11-year-olds who use public transport in a large metropolitan centre with assurance be free to wander around their own suburban streets unfettered? Evidence also suggests not. So what is going on? Why is space so imbued with social rules and behavioural codes, and what is it that determines these? Is it something intrinsic to space itself; is it something intrinsic to the society and to the societal meanings placed on space; or is it some combination of these? These are some of the questions explored in this book.

In their planning and design, most spaces ignore children as users

Space in all its variations – home, school, street, bus stop, shop, soccer pitch, playground, health clinic, library, garden, city centre, public square, to name but a few – forms an integral component of the child’s world. Yet in their planning and design most of these spaces ignore children as users. This was brought home very clearly in research that Freeman and Aitken-Rose (2005a, 2005b) undertook with local authorities in New Zealand. In this study planners were asked about how and where they took children into account in planning. The responses invariably were that planners considered children in planning for recreation, mainly playgrounds and sports, and in planning for education, schools and crèches. Planners were particularly pleased at being able to recount how they were taking young people into account in the processes around planning for skate parks. For what other sector of society would one ‘minority’ and highly gendered sporting activity be seen as meeting general social and sporting needs? Also, what other sector of society would have their needs ignored when planning homes, streets, roads, shops, health and leisure facilities, transport and infrastructure? Planners also held simplistic notions of children, characterized by a concept of a universal child, homogeneous and undifferentiated: a boy of a certain age is assumed to be almost definitely interested in skateboarding. Children are not like that; their lives are not like that. We do not plan for a ‘universal, uniform prototype adult’. Like adults, children reflect the infinite variety of life, culture, age, race, gender, experience, character, level of ability, likes and dislikes, and are differentially affected by the environments and processes of environmental change. In the city children do more than recreate and be educated (as the planners believed). They use the whole city. As Colin Ward said: ‘I want a city where children live in the same world as I do … [where if] the claim of children to share the city is admitted, the whole environment has to be designed and shaped with their needs in mind’ (Ward, 1978, p204).

The whole environment has to be designed with children’s needs in mind

The New Zealand planning research acted as an impetus for this book (Freeman and Aitken-Rose, 2005a, 2005b). It revealed the need to consider children in all societal variations, across different types of environments and with recognition of difference in children’s experiences and use of space. Seeking to understand this relationship is, however, only a recent occurrence in the annals of social and environmental history.

Changing Contexts and Conceptualizations of Children’s Lives

There has been considerable and growing interest in children over the last 30 or so years. A number of texts have explored the changing position of children in society. It is a task made difficult by the paucity of recognition that children are given in historical records. In part, this is symptomatic of the fact that for much of history children were not necessarily seen as separate or distinguishable from adults. Some authors focus on the negative permutations of childhood to explain its relative absence. Lloyd deMause (1974) goes so far as to state that ‘the history of childhood is a nightmare from which we have only recently begun to awaken’ (in Jenks, 2005, p326), and then proceeds to paint a most depressing picture of childhood historically as a period of abuse and misuse. In his fascinating book Childhood in World History, Stearns (2006) again refers to the problem of writing on history given the lack of records, pointing to the futility of trying to generalize childhood with its multiple manifestations across time and in different societies. In the midst of this uncertainty, what is undisputed is that, historically, childhood was a time of great uncertainty: death of children was common, families were large and the investment of time and resources by families in any individual child was minimized, at least until the child had proved some likelihood of survival into adulthood. Authors such as Stearns demonstrate that interest in childhood as being worthy of dedicated study is a relatively recent phenomenon, one only coming to the fore in the latter half of the 20th century.

The child’s place and role in society has been the focus of robust debates. Positions within this debate can be held strongly, with children being seen as everything from vulnerable innocents, blank canvases, young adventurers and deviants to competent social actors. These differing positions have informed markedly different approaches to the exploration of childhood and children’s environments. Postman (1994) writes of the ‘disappearance of childhood’, lamenting the loss of innocence as children are too soon inveigled into the not-so-innocent worlds of adulthood. More recently, Donahoo (2007) bemoans what he calls the ‘idolising of children’ where the pendulum has swung far in the direction of exhorting the creation of impossibly ‘ideal’ childhoods, an ideal that neither children nor parents can comfortably or realistically achieve. In a similar vein, Furedi (2008) decries what he sees as the rise of ‘paranoid parenting’: the seeing of danger in all elements of childhood such that any sense of perspective on real dangers is lost. The outcome of ‘paranoid parenting’ is the continual adoption of risk-averse behaviour: behaviour that is counter-intuit...