What is reading?

We all know what reading is. And many of us have suffered, at some time or another, from the type of bore who stops any argument or discussion with ‘Ah, it depends on what you mean by …’. So it is with some reluctance that we begin this part with an attempt to define reading, to say what we mean by the term. Our excuse is that people do use the term in different ways, and that while this may be permissible when everyone is conscious of the differences, on other occasions it can cause real confusion and difficulty.

Like Bernhardt (1991b) we approach the problem via dictionary definitions. The Concise Oxford Dictionary gives thirteen entries for the word read, of which twelve refer to the verb. Below we give, in an abbreviated form, the first three:

- interpret mentally, declare interpretation or coming development of (read dream, riddle, omen, men’s hearts or thoughts or faces)’,

- (to be able to) convert into the intended words or meaning written or printed or other symbols or things expressed by such symbols …; reads or can read, hieroglyphics, shorthand, Braille, Morse, music…;

- reproduce mentally or … vocally, while following their symbols, with eyes or fingers, the words of (author, book, letter, etc.); read the letter over…

We should say right away that none of these, or in fact any of the entries we mentioned, matches precisely our own definition of reading, which goes some way towards excusing our spending time on such definitions. That apart, for our purposes here, we can from now on reject definition 1 above. It is obviously a legitimate use in the English language of the verb read, but we are using the term in relationship to written texts, and so will not include uses like reading dreams in our definition. It is worth pointing out, however, that this first entry seems to focus on the use of the verb to mean something like interpret, which is an important aspect of text reading. Entry 3 looks as if it is largely confined to the activity often referred to as decoding, and will be discussed below. Entry 2 looks the most promising, but even here there is a problem. For reasons which will be discussed shortly, we will consider it appropriate to refer to reading hieroglyphics, or shorthand, Braille or Morse. However, we shall not use the term to include the reading of music, or, for example, maps, or mathematical symbols, etc. The reason for this apparently arbitrary decision rests on a prior definition of what is meant by writing.

In his book on writing systems, which will be referred to at several points in this chapter, Sampson (1985) finds it necessary to devote several pages to defining ‘writing’, just as we are having some difficulty defining ‘reading’. One of the main difficulties facing Sampson is the fact that there exist written or printed symbols which would not normally be referred to as ‘writing’. The international road sign for ‘bridges ahead’ is one example, as are the symbols distinguishing men’s from women’s toilets, and so on. Sampson distinguishes between glottographic symbols, which represent language, and semasiographic symbols, which do not. Thus the printed word three is glottographic: it actually represents the English word pronounced [θri:]. The figure 3, on the other hand, is semasiographic. While it can be ‘translated’ by the English word three, it can also represent trois, or drei, or tatu, or words all meaning ‘three’ in any number of languages. Mathematical symbols, in fact, represent a very sophisticated semasiographic system, as does musical notation. Here we follow Sampson in not counting semasiographic systems as writing; hence the interpreting of messages in such systems will be considered as being outside the scope of reading proper. Reading, as used here, will mean dealing with language messages in written or printed form. That is why, when discussing the COD entries above, we accepted Braille, hieroglyphics and Morse as messages suitable for reading, but excluded music.

This restriction on the term may strike some of our readers as unduly narrow. From a practical point of view, for example, written messages often include semasiographic symbols, perhaps mathematical figures, or maps, and so on. ‘Communicative’ reading material often includes maps and time-tables, which the student reader is expected to process along with any written material. Surely it seems pedantic to say that someone reads a message until they come across a figure, at which point they stop reading and begin another activity? And if we don’t read bus time-tables, what do we do with them?

However, there are good reasons for the restriction. Perhaps the most important, for our purposes, is that reading involves processing language messages, hence knowledge of language. We do not want to become embroiled in the controversy as to whether language competence is separate from, and, in its acquisition, quite different from other areas of competence such as mathematical knowledge. We would, however, consider it fairly uncontroversial that the process of reading, certainly above the level of decoding, makes demands on linguistic competence which are more immediate and more pervasive than appeals to other competence areas.

Secondly, in the classroom, a distinction between reading and other symbol-processing activities is made, even though it may not be made consciously. LI primary school teachers, or EFL teachers, may incorporate semasiographic material in reading lessons, but they are not likely to think of themselves as teaching students how to read, for example, maps. The presence of maps, etc., in reading lessons is incidental to the main teaching focus, which is on how to read language messages. Neither of the present authors can read music, but neither found themselves in a remedial reading class, on that account at least.

Finally, our use of the term reading seems to agree with the non-technical, everyday use of the word. Faced with a questionnaire asking about hobbies, the person who gets a thrill out of perusing mathematical formulae is not likely, with that in mind, to respond with ‘reading’. That answer is restricted to those who derive pleasure from newspapers, novels, history books, etc.

Before leaving this point, we need to clarify what we mean by language. After all, mathematics is often described as being a kind of language; but so is formal logic, and we often talk of computer languages. What we mean, here, however, by the term are languages such as French, Swahili, Mandarin and so on. Sampson refers to them as ‘oral languages’, but immediately has to qualify this by saying that an ‘oral’ language is not necessarily ‘spoken’, which seems rather confusing. We might refer to ‘natural’ languages, except that this term tends to be used to contrast languages such as French, Japanese, etc., with ‘artificial’ languages such as Esperanto. From our point of view, Esperanto is a language, just as English is, and can be read as such. Perhaps at this point we just have to rely on our readers’ knowledge of the world, and assert that we are using the term ‘language’ to refer to French, Esperanto, etc., linguistic languages as it were, and not to mathematical or computer languages.

The fact that the information conveyed by a written message is encoded in language obviously has major pedagogical consequences. At the moment, we simply point out that for people learning to read in their native language, it is clearly relevant that they already know the language, or at least a significant part of it. As opposed to the learning of mathematics, that is, the learner does not need to learn both the conceptual system and the conventions of encoding it. And the fact that LI learners of reading have this advantage is not affected by whether we take the pedagogical decision that ‘all’ they need to learn is to decode, or whether we decide to make use of previously acquired language knowledge in the process of learning to read.

As far as the L2 situation is concerned, the fact that reading involves processing language should perhaps make us a little sceptical of dichotomies, found in the literature (e.g. Alderson, 1984), as to whether L2 reading difficulties are ‘reading’ or ‘language’ problems. It may be difficult to distinguish the two. This question is addressed in more detail in Chapter 5.

Reading and language

The texts which we read, then, are language texts. So reading is involved with language texts. But what is the relationship between reading and language? Roughly speaking, there are two answers to this in the literature. The first defines reading as decoding, as Perfetti (1985) glosses it, ‘the skill of transforming printed words into spoken words’. This decoding definition offers some good arguments. It delineates a restricted performance and allows a restricted set of processes to be examined. However, as Perfetti points out, it has limited popularity partly because it has limited application to the demands of actual reading. Moreover, it is not really feasible to view decoding as the initial process which is over by the time other cognitive linguistic processes begin. In one of the best-known papers on reading, Goodman (1967) argues that syntactic, semantic and pragmatic knowledge are involved in the decoding process. And this is the position of those advocating an interactive model of the reading process, discussed in Chapter 2.

Finally, a practical, commonsensical view of certain activities should persuade us that decoding cannot be equated with reading. Given the regularity of sound/letter correspondences in the spelling of Spanish, for example, it would be possible, if fairly pointless, to teach an English speaker who knows no Spanish to read aloud from a Spanish text with reasonably good pronunciation, but no comprehension. Few sensible people, however, would describe such an activity – sometimes referred to as ‘barking at print’ – as reading, even though activities resembling it are carried out under the guise of ‘teaching reading’ in many parts of the world. (In a seminar conducted by one of the authors, a British teacher remarked thoughtfully, ‘I have a boy in my class who’s a really good reader. The problem is he doesn’t understand anything he reads.’) We conclude that decoding must be an important part but not the whole of the reading process.

The second answer defines reading as the whole parcel of cognitive activities carried out by the reader in contact with a text. Thus Nuttall (1982), having considered definitions of reading in terms of reading aloud, or decoding, settles for the extraction of meaning from written messages. Similarly, Widdowson (1979) has defined reading as ‘the process of getting linguistic information via print’. And Perfetti, as the alternative to a definition in terms of decoding, suggests that reading can be considered as thinking guided by print, with reading ability as skill at comprehension of text.

Perfetti’s second definition, that reading is thinking guided by print, also has problems. Those who have trouble with reasoning or fail to learn from reading will be said to have reading problems. Clearly the difficulty here is one of establishing boundary lines, and being able to say, ‘Up to here we have reading problems, beyond …’. The problem is present in an ambiguity in Widdowson’s definition. One could say that ‘linguistic information’ was restricted to information about, say, syntax, morphology and lexis. Perhaps we can emend the definition to read ‘information carried by linguistic messages via print’. The open-ended nature of what some people mean by reading is what Fries (1963) was commenting on, when he remarked, of ‘broadly based’ educational approaches to reading:

But we should certainly confuse the issue if we insist that this use of reading in stimulating and cultivating the techniques of thinking, evaluating and so on, constitutes the reading process.

There is a real difficulty here, one that has resurfaced in recent years in the debate about ‘reading skills/strategies’ as opposed to ‘language skills/strategies’. Here, however, in spite of the difficulties associated with defining reading in such an open-ended way, we consider reading to be a language activity, involving at some time or another all the cognitive processes related to language performance. Thus we consider that any valid account of the reading process must consider such cognitive aspects as reading strategies, inferencing, memory, relating text to background knowledge, as well as decoding, and obvious language aspects as syntax and lexical knowledge. In this respect, at least, we are in agreement with the proponents of ‘critical reading’, discussed briefly in the Introduction.

This would seem, in practice, to be the position most favoured by teachers and materials writers. Many reading textbooks, for example, contain practice in such cognitive activities as drawing conclusions on the evidence of written messages, making inferences, evaluating texts in terms of truth, persuasiveness, beauty, etc. It would be hard to find an EFL reading textbook which restricted activities to decoding. In fact, it is quite difficult to find one that includes any explicit material on decoding at all.

The same is true in the research area. In an editorial in the Reading Research Quarterly in 1980,1 under the heading ‘Why Comprehension?’, the editors comment that an emphasis in the 1960s on decoding and early reading attracted much less attention in the 1970s, being replaced by an emphasis on comprehension.

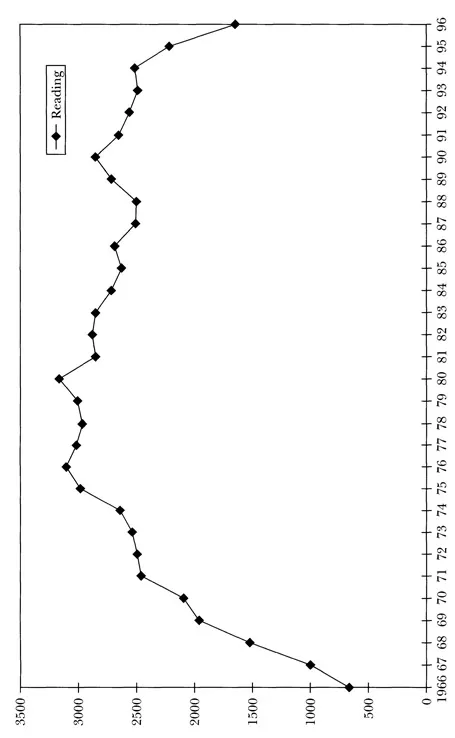

This view can be substantiated by statistics: Figure 1.1 based on data from ERIC,2 shows the number of articles and other publications, published between 1966 and 1996, which mention the term reading in their title, or in ERIC’s index or abstract. The graph shows a rapid increase in such papers in the latter part of the 1970s, presumably reflecting a major increase in interest in reading. (It also, of course, shows a gradual decline from that peak, which we are unable to account for, although the very rapid decline after 1994 may have something to do with methods of data collection.)

Figure 1.1 Number of articles and other publications published between 1966 and 1996 that mention ‘reading’ in their title or in ERIC’s index or abstract (based on data from ERIC).

The rapid rise after 1966 is paralleled by a rise in inte...