- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Creativity Across Domains: Faces of the Muse sorts through the sometimes-confusing theoretical diversity that domain specificity has spawned. It also brings together writers who have studied creative thinkers in different areas, such as the various arts, sciences, and communication/leadership. Each contributor explains what is known about the cognitive processes, ways of conceptualizing and solving problems, personality and motivational attributes, guiding metaphors, and work habits or styles that best characterize creative people within the domain he or she has investigated.

In addition, this book features:

*an examination of how creativity is similar and different in diverse domains;

*chapters written by an expert on creativity in the domain about which he or she is writing;

*a chapter on creativity in psychology which examines patterns of performance leading to creative eminence in different areas of psychology; and

*a final chapter proposing a new theory of creativity--the Amusement Park Theoretical Model.

This book appeals to creativity researchers and students of creativity; cognitive, education, social, and developmental psychologists; and educated laypeople interested in exploring their own creativity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The Creative Process in Poets

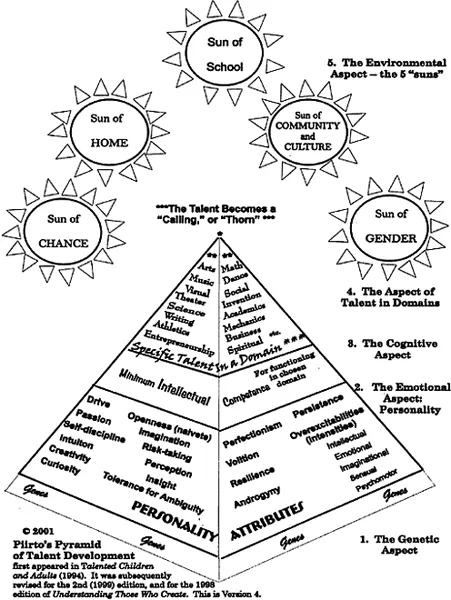

THE PIIRTO PYRAMID OF TALENT DEVELOPMENT

1. The Genetic Aspect

2. The Emotional Aspect: Personality

Table of contents

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: How People Think, Work, and Act Creatively in Diverse Domains

- Chapter 1 The Creative Process in Poets

- Chapter 2 Flow and the Art of Fiction

- Chapter 3 Acting

- Chapter 4 Should Creativity Be a Visual Arts Orphan?

- Chapter 5 Creativity and Dance—A Call for Balance

- Chapter 6 Musical Creativity Research

- Chapter 7 Domain-Specific Creativity in the Physical Sciences

- Chapter 8 Creativity in Psychology: On Becoming and Being a Great Psychologist

- Chapter 9 Creativity in Computer Science1

- Chapter 10 Engineering Creativity: A Systems Concept of Functional Creativity

- Chapter 11 Creativity as a General and a Domain-Specific Ability: The Domain of Mathematics as an Exemplar1

- Chapter 12 Creative Problem-Solving Skills in Leadership: Direction, Actions, and Reactions1

- Chapter 13 Emotions as Mediators and as Products of Creative Activity

- Chapter 14 Selective Retention Processes That Create Tensions Between Novelty and Value in Business Domains

- Chapter 15 Management: Synchronizing Different Kinds of Creativity

- Chapter 16 Creativity in Teaching: Essential Knowledge, Skills, and Dispositions1

- Chapter 17 The Domain Generality Versus Specificity Debate: How Should It Be Posed?1

- Chapter 18 The (Relatively) Generalist View of Creativity

- Chapter 19 Whence Creativity? Overlapping and Dual-Aspect Skills and Traits

- Chapter 20 The Amusement Park Theory of Creativity

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app