eBook - ePub

Spatial Cognition

The Structure and Development of Mental Representations of Spatial Relations

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Spatial Cognition

The Structure and Development of Mental Representations of Spatial Relations

About this book

First published in 1983. This is a volume in a series on Child Psychology. This book offers a set of theoretical ideas which make up a quite general theory of the mental representation of space which accounts both for much of spatial perception but also much of spatial thought. The system is general and economical and can be readily applied to novel problems as we illustrated in regard to Piaget's water level problem and Koler's letter recognition problem.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Spatial Cognition by D. R. Olson,E. Bialystok in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Spatial Aspects of the Mental Representation of Objects and Events |

“Has the oyster [a] necessary notion of space?”

Darwin’s Notebooks.

I. ON SPATIAL COGNITION

A historical account of the conception of space and the transformations that conception has passed through—from Aristotelian to Newtonian to Einsteinian—could serve as an account of the development of intellect. These insights into physical space, as several writers have pointed out (Butterfield, 1965; Cornford, 1936; Eddington, 1958) rest upon parallel discoveries in conceptual space—the spherical but bounded Void of Pythagoras, the infinite, continuous space of Euclid and the elastic space of Lobatchvsky. The most obvious effect of these discoveries has been to alter our conception of the external world; but just as important, it has altered our conception of human cognition. If what we call physical reality is to be dependent upon certain conceptual or mental ideas, as for example the infinite, continuous, physical space of Newton is to be seen as the expression of the infinite, continuous, conceptual, space of Euclid, then it is impossible to explain the structure of human cognition by recourse to the structure of physical reality. That is, the structure of ideas cannot be explained by recourse to the structure of reality. The noted physicist, Sir Arthur Eddington (1958) made this point most strongly:

… not only the laws of nature, but [of] space and time, and the material universe itself, are constructions of the human mind … To an altogether unexpected extent the universe we live in is the creation of our minds.

The ball, so to speak, is in our court. Can we develop some description of the operations of the human mind which will account for some of the properties of invented conceptual space and the ways in which this conceptual space is employed in perceiving, recognizing and remembering objects and events? What is the structure of the cognitive processes by means of which we represent and interpret the world? What is the relation between the cognitive structures that are employed in everyday perception and action and those that are involved in our scientific representations of reality? What is the role of symbols in those cognitive processes?

Our assumption is that spatial concepts and spatial relations play a fundamental role in the cognitive structure at every level of representation from object perception to formal geometry. Furthermore, spatial structures are exploited far beyond their concrete representational functions. We may announce the topic of this book by saying it is on space, or that the theory is an extension of some earlier work, or that it is within the field of cognitive psychology or that it examines the processes which lie under or behind the perception and knowledge of space, and so on.

Our concern is with the problem of inner space or spatial cognition, the spatial features, properties, categories and relations in terms of which we perceive, store and remember objects, persons and events and on the basis of which we construct explicit, lexical, geometric, cartographic and artistic representations.

We shall argue that we perceive and act in our environment on the basis of concepts of objects, persons, and events constructed in large part out of features and relations which are spatial. Spatial properties may be used to recognize objects by shape, to remember locations by positions, by landmarks, and by adjacency, and to judge safety and danger by sizes and distances. But, and here again, we are at our central question, how is that spatial information coded and utilized in the service of these various activities?

Not only is spatial information critical to object, person, and event perception, but also space comes to be perceived in its own right in terms of spatial concepts—tops and bottoms, round and square, open and closed and the like, when represented in such symbol systems as ordinary language, map-making, drawing, graphing and painting. This, then, is our second question: How are these explicit spatial concepts related to the spatial information that is implicit in object, person, and event perception?

The spatial information, as we shall see, is largely preserved from object perception to spatial conception—from perceptual space to representational space as Piaget would say—but it differs in terms of the meaning system of which it is a part. But how, and this is our third question, does meaning relate to perception of objects and to our conception of space? What is the role of meaning in perception? Traditional accounts of perception, because of their lack of concern with meaning, fail in two primary ways (both coming and going if we may be excused a spatial metaphor). They fail to acknowledge that what people perceive are objects and events, not spatial/visual features—and they fail to recognize that perceptual distinctions reflect meaning differences rather than determine them.

We shall present our arguments in a series of stages. Firstly, we shall set out to describe a form of mental representation which jointly specifies the meaning of objects and events and the spatial information appropriate to the perception of these objects and events. Secondly, we will describe the processes whereby these structural descriptions of objects and events are “interrogated” to form explicit spatial concepts with their own distinctive meanings. Spatial concepts too are represented by means of structural descriptions but they are organized at a new level of meaning which we call representations of form to differentiate them from representations of objects and events.

The interplay between the implicit structural descriptions of objects and the explicit form representations of spatial concepts provides a basis for a discussion of the traditional problem of perception and representation and for outlining aspects of a theory of cognitive development.

Finally, a series of studies is presented which examines the nature of the spatial information utilized in the structural description of objects and events, the development of spatial concepts, the lexicalization of space, and the ways that these alternative forms of representation are recruited in solving some classical spatial tasks. We conclude with a general theory of spatial representation and spatial thought which can be used to explain a wide array of tasks from Piaget’s motor level task to letter recognition.

II. PERCEPTION AS A SPATIAL PROBLEM

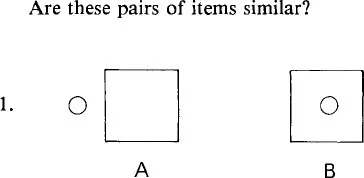

Without reflection we would tend to say that they looked very different. What was the basis for our decision as to their dissimilarity? Possibly, for A we would say that the circle is beside the square and for B that the circle is inside the square, and so on. But we would hesitate to claim that that statement bore much relation to the psychological processes involved in making that similarity judgement. Rather, they just seemed to look different.

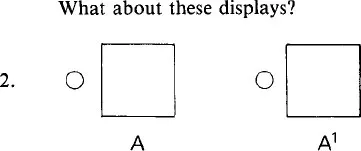

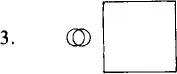

They appear to be very similar. Why? We may say that they both have a circle to the left of a square so they look alike. However again we would hesitate to state that our perceptual processes directly corresponded to our linguistic description. A possible alternative to the theory that we compared linguistic or linguistic-like descriptions is that A and A1 look alike because the image of one matches the image of the second much as if one picture were superimposed upon another. But, at least in this case the explanation seems inadequate. Here is a picture of the two superimposed:

The images do not fit. Why then did we judge them as similar? The image matching view seems to fall short. No two things are identical and yet we readily judge them as similar or treat them as equivalent—This is Bill; this is a photograph of Bill. This is the Mona Lisa; this is a reproduction of the Mona Lisa, and so on. How do we judge them equivalent if they are not identical? How do we recognize a person’s face as the same face if on one occasion it is smiling and on another frowning?

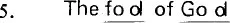

Not only are discriminable displays seen as similar or identical but identical things are seen as different. Furthermore not all stimulus differences are equally important in deciding upon the similarity of displays. Consider the book title in 5.

Do the last letters in the underlined words look the same? In fool we tend to note the space between the o and l; in God we tend to overlook it—in order to make sense they must be seen as joined to make a d. If similarity judgements are based upon uninterpreted images or copies then any stimulus change should be as important as any other change. Yet in example 5, the same perceptual information, that is, the space between the o and 1 was perceived in two different ways. Recognition of displays seems to involve procedures that are more “intelligent” than the simple copying of visual displays. But, again, how are we to account for that “intelligence”?

What we perceive, recognize or judge as similar or identical depends, we shall argue, upon what we know, that is, on the meanings we can assign to a display. What we know—our expectancies and our interpretations in conjunction with the sensory display determine what we perceive.

The theory that meaning is a critical part of perception has had a mixed career. Two arguments, both reductionistic, have contributed to underestimating the role of meaning in perception. First, meaning is usually taken as a higher order “interpretation” of experience, while perception is a direct consequence of that experience, hence, meaning appears to have a secondary or derived status. The second was the general reductionist assumption that higher order structures could be explained in terms of lower order ones, hence, meanings could be explained in terms of the uninterpreted sensory properties captured in the act of perception. These arguments are readily traced to the British empiricists and to sense-data theorists since, including the behaviorists, who took sensation as the basis of all knowledge. The mind merely collected and associated such sensations to produce the knowledge of objects and events. If sense-data were primary in experience, complex concepts would be explained in terms of those more fundamental sense-data. Furthermore, if sense-data were picked up directly, without interpretation they could be both taken as “brute fact” and used as firm base for subsequent theoretical knowledge (Taylor 1964). Sense-data, then, reflected the world more directly and truly than did theories. Language too was to be restricted to “plain speech”, an empirical object-based language with a rejection of “all amplifications, depressions and swellings of style” and the use of “an equal number of words for an equal number of things” (Sprat, 1657/1966).

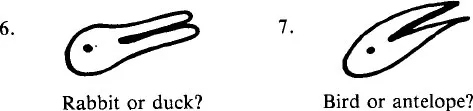

Nonetheless, there have been others urging us in the opposite direction for several decades. The Gestalt psychologists provided many demonstrations that perception was not merely the preservation of a visual copy of a display but rather an interpreted structure. Various types of illusions, the Necker cube, the Muller-Lyre illusion, as well as (6) the duck-rabbit, and (7) the bird-antelope were given as examples that perception is not merely the registration of objective form but rather is “laced” with interpretation. Furthermore, the interpretation determined what was seen.

Rock (1978) has extended these arguments by showing that the illusions of apparent motion are the consequence of what we know about the motion of real objects. Again our perceptions are informed by our knowledge of the world.

Wittgenstein (1958), in his examination of two meanings of the word “see” discussed just this problem. In one sense of “see” we mean what remains invariant in our varied interpretations of the display while the other sense of “see” we mean the various likenesses, or interpretations we put upon that display. “I see that it has not changed; and yet I see it differently. I call this experience ‘noticing an aspect’” (p. 193). But he goes on to argue that these seeings are not ordered, one being perception and the other interpretation. Rather “we see it as we interpret it” (p. 193). And again, “It is a case of both seeing and thinking? or an amalgam of the two, as I should almost like to say?” (p. 197). “But how is it possible to see an object according to an interpretation? The question represents it as a queer fact; as if something were being forced into a form it did not really fit. But no squeezing, no forcing took place here” (p. 200). That is, the two meanings tend to collapse into one: “Do I really see something different each time, or do I only interpret what I see in a different way? I am inclined to say the former” (p. 212).

Hanson (1958) has applied this view of the inseparability of seeing and interpreting to modern physics. In contrast to the classical view of physics (akin to that of the British Empiricists mentioned above) in which data, facts, and observations are first collected and build up into general systems of physical explanation, Hanson examines how those theoretical systems are built into observations, facts, and data. Hanson argues that observation is always shaped by our theories and interpretations. He illustrates this view with a colorful description of a hypothetical discussion about cosmological space:

Let us consider Johannes Kepler: imagine him on a hill watching the dawn. With him is Tycho Brahe. Kepler regarded the sun as fixed: it was the earth that moved. But Tycho followed Ptolemy and Aristotle in this much at least: the earth was fixed and all other celestial bodies moved around it. Do Kepler and Tycho see the same thing in the east at dawn?… The resultant discussion might run:

Yes, they do.

No, they don’t.

Yes, they do!

No, they don’t!… (p. 5).

Hanson goes on to argue that by possessing different theories, they see different things or at least things differently. Kepler sees the horizon dropping while Tycho sees the sun rising. Hanson rejects the argument that one first sees a display and then assigns an interpretation to it. “There is a sense, then, in which seeing is a ‘theory-laden’ undertaking. Observation of x is shaped by proper knowledge of x…‘Seeing that’ threads knowledge into our seeing” (p. 19–22).

In his analysis of the problem of representation in art, Sir Ernst Grombrich (1960) examined in detail the relation between what one perceives and what one knows in general and how one comes to see in a way that permits a faithful representation in art, in particular. He argues that in order to describe or portray the visible world in art one needs a developed system of schemata. These schemata are compared to a questionnaire or formulary which selects information from the visual world; only those aspects of information that are judged to be relevant or useful are registered in the schemata. The objective of the artist, that is, his conception of what he is trying to do, together with the visual forms that he already knows or can portray, will determine what information he gains from his perceptions of the world.

In his Retrospect to the book Art and Illusion Gombrich noted: “We have come to realize more and more, since those days, that we can never neatly separate what we see from what we know” (p. 394). We shall return to a fuller account of Gombrich’s views in our discussion of development.

There are two points to notice here. Firstly, what one sees depends upon what one knows, that is on the schemata, concepts, or codes available. And secondly, what one must see to make a representational drawing is different from what one ordinarily sees in objects and events. It may be tempting to think that ordinary seeing is direct perception, that is seeing things as they really are, while artistic perception involves seeing through or seeing in terms of the properties of the codes or schema appropriate to that specialized medium of representation. That view is explicitly rejected by all of the lines of argument we have summarized here—even ordinary perception is laced with knowledge or interpretatio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Spatial Aspects of the Mental Representation of Objects and Events

- 2. On the Formation of Structural Descriptions and Meanings for Objects and Events

- 3. Representations of Spatial Form

- 4. The Development of Spatial Cognition

- 5. Aspects of the Development of the Spatial Lexicon

- 6. The Development of Strategies for Solving the Perspective Task

- 7. The Development of Strategies for Coordinating Spatial Perspectives of an Array

- 8. On the Representations and Operations Involved in Spatial Transformations

- 9. The Education of Spatial Transformations

- 10. On Children’s Mental Representation of Oblique Orientation

- 11. On the Mental Representation of Oblique Orientation in Adults

- 12. Explaining Spatial Cognition: A Theory of Spatial Representation

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index