This book is available to read until 25th January, 2026

- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 25 Jan |Learn more

Energy: The Basics

About this book

People rarely stop to think about where the energy they use to power their everyday lives comes from and when they do it is often to ask a worried question: is mankind's energy usage killing the planet? How do we deal with nuclear waste? What happens when the oil runs out? Energy: The Basics answers these questions but it also does much more. In this engaging yet even-handed introduction, readers are introduced to:

- the concept of 'energy' and what it really means

-

- the ways energy is currently generated and the sources used

-

- new and emerging energy technologies such as solar power and biofuels

-

- the impacts of energy use on the environment including climate change

-

Featuring explanatory diagrams, tables, a glossary and an extensive further reading list, this book is the ideal starting point for anyone interested in the impact and future of the world's energy supply.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Energy: The Basics by Harold Schobert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Ecología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

ENERGY AND US

It all hinges on energy—everything we do. At home, energy is important for heating, lighting, and cooking. But, cooking means that we have to have something to cook. Having food requires farming, which means agricultural machinery that operates with fuel, or relying on animals that require their own food sources. Harvested food has to be transported, processed, prepared, and packaged. Packaged food is transported to warehouses and stores for sale to us. Every aspect of daily life depends on a variety of manufactured articles. Not many of us these days weave cloth, turn logs into boards, or make any of the other items we use throughout the day. Manufacturing begins with producing raw materials, which then must be fabricated into useful articles. Manufactured articles must also be transported to stores. Daily activity involves getting out of the home for work, shopping, or socializing. If we walk or bicycle, we use energy from our own muscles for transportation. Carts or carriages pulled by animals, cars or light trucks, buses, trains and airplanes all consume energy in some form. The many uses of energy in the home for warmth, cooking and lighting, together with farming, manufacturing and transportation consume prodigious quantities of energy.

Many people in the industrialized world are fortunate to be able to surround themselves with electrical appliances and gadgets: television, microwave oven, music system, personal computer, electric razor, hair dryer, refrigerator, lamps, coffee maker, electric clock, electric pencil sharpener, electric tooth brush, power tools, and radio—and, for some of these items, often more than one of each. In many kitchens one can expect to find a stove, a refrigerator, a dishwasher and a microwave oven. What else? A coffee maker, espresso machine, electric can opener, pasta maker, bread maker, crock pot, electric carving knife, toaster or toaster oven (or both), and a blender or food processor. When buying one of these items, nobody worries about whether there will be enough electricity to operate them. If there's a problem, it's how to find counter space to use all this stuff, or cabinet space to store it.

Even asking whether there would be ‘enough’ electricity to operate a gadget we're buying when we get it home probably sounds silly. We assume that we can buy and plug in a limitless number of electric appliances. If we even think of a limit, it's the number of outlets available for plugging items into. We can even solve that problem if we remember to buy some power strips (that provide five or more electrical outlets from an original single outlet).

The assumption about the eternal availability of unlimited quantities of electricity is tested when there is a power failure. When that happens, we might have a momentary bit of panic, but then many of us react to a power failure with a feeling of annoyance or anger. We were watching that TV show, or cooking that meal, or reading that book, feeling that we could do those sorts of things as much as we wanted, any time we wanted, and now, suddenly—no electricity. No TV, no cooking, no reading, no music, the computer may have just died … life's dark in more ways than one.

Not everyone in the world enjoys the lifestyle that's just been described for the residents of prosperous, industrialized countries. In too many places in the world, if electricity is available at all, it is only ‘on’ for a limited time each day. A quarter of the world's population—1.5 billion people—lacks ready access to electricity. In some places, such as Burundi and Rwanda, more than 80% of the population lacks electricity entirely.

In the United States, we usually have the same attitude toward gasoline. We expect to be able to drive without worrying about whether we will be able to buy gasoline whenever and wherever we need it, and as much as we want. Even at 2 a.m. on Christmas morning some convenience store, somewhere, is open for those who want to buy gasoline. Gasoline seems to be as easily and widely available as water. Gasoline shortages, or sudden price spikes, produce the same anger as electricity outages.

As with electricity, the ready availability of gasoline is not the case everywhere, only in the developed or industrialized nations. The world's cheapest gasoline is in the Persian Gulf region, in those countries having significant amounts of oil: Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait as examples. In many industrialized nations with strong economies, such as Japan and Western Europe, gasoline costs two to three times as much as in the United States.

For those people fortunate enough to live in reasonably prosperous, industrialized nations, energy is readily and always available at the flick of a switch, stopping at a filling station, or plugging an appliance into a wall socket. The key idea that should come from thinking about how we get through the day is this:

Energy is ubiquitous in our lives and is so common that we seldom even think about it.

Another way of illustrating our dependence on energy is to consider it from the other perspective: how we would live if the supply of electricity, petroleum products, and natural gas suddenly was not available any more. What would we eat? Foods raised by ourselves or foraged in the outdoors. How would we get around? Most of us would be confined to an area accessible by walking, or on horseback. How would we stay warm? Firewood, if we had access to it, and only for as long as the wood lasted. A few clever persons might rig up solar energy collectors, or figure out how to use windmills or water wheels to produce electricity. What would we use in our daily lives? Clothes, tools, and utensils that we have now, until they broke or wore out. There would be no replacements, except for things made of wood, or wool or cotton cloth. How would we regulate our days? Rise at dawn and go to bed at dark, because there would be little artificial light other than fires. Most people—especially city dwellers—might freeze and starve in the dark. Survivors would be reduced to a brutish existence not unlike that experienced by the poor during medieval times. A very few, those who were competent at subsistence farming and at the manufacturing or repairing of small tools and machinery, might ‘make it.’

ENERGY AND NATIONS

Before the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century, society relied on three energy sources: human and animal muscles, firewood, and the energy of wind and water. Since then, there have been three major historical transitions in our use of energy. First came the steam engine, fueled mostly by coal. Second was the development of electricity. Electricity was the first form of energy for which its place of production could be separated by large distances from the place of its use. It is also the only energy source easily converted into light, heat, or mechanical work wherever it is used. Third was the internal combustion engine, which introduced enormous mobility into society, at a cost of a significant dependence on petroleum products. Petroleum became the dominant global energy source by the end of the twentieth century.

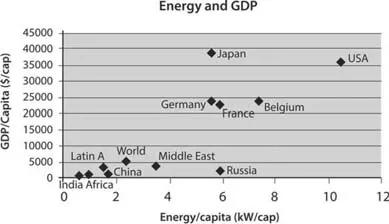

In most countries of the world, growth in energy consumption relates to income growth (e.g., Figure 1). This relationship holds for many countries over a period of years. Until about 1975 there was a fairly good correlation between the economic wellbeing of a country, as measured by its total output of goods and services (gross domestic product, GDP) and its energy consumption. The countries with the largest GDP tended to use the most energy, while undeveloped economies used less energy.

Figure 1 This graph shows a relationship between per capita energy use and gross domestic product for various countries. ©2007, John E.J. Schmitz. As a rule, countries with a higher per capita energy use also have a higher gross domestic product.

Population growth and technological progress are the major considerations affecting economic development. As a country develops, GDP growth occurs through an increase in population—demand for housing, transportation, consumer goods, and services—and results in an increase in energy consumption. During that time, growth of GDP paralleled energy consumption.

The last quarter of the twentieth century saw a change in the relationship between GDP and energy use, especially in developed countries. By 2000, energy use per dollar of GDP was dropping at about 2% per year. The decline means that we are more efficient at generating goods and services from the amount of energy we use. The dollars of GDP produced for a given amount of energy consumed should rise as we do a better job at producing goods and services from a given amount of energy. In fact, it is doing exactly that.

Several factors contributed to this change. From 1945 until the early '70s the cost of energy (adjusted for inflation) dropped. Many utilities encouraged consumers, even with cash incentives, to use as much electricity or natural gas as they wanted. The oil price shock in the early '70s caused industries to operate in ways to reduce energy consumption. There had been no incentive to do this in the era when the cost of energy was dropping. A second factor is the transition of developed countries to the so-called post-industrial society: a transition from an industry-based to a service-based economy, which requires much less energy. The industries that remain in the post-industrial economy tend to be ones that add considerable value to the materials or components but require relatively little energy, such as making computers; heavy, energy-intensive industries such as steel or cement move out.

Worldwide, enormous differences exist in levels of economic development, standards of living, and access to energy. The richest one-fifth of the world's population consumes about four-fifths of the world's goods and services, and uses about half the world's energy. The poorest one-fifth of the world's people consume 1% of goods and services, and get by on about 5% of the world's energy. Per capita GDP differences among countries reflect differences in economic structure—i.e., whether the country is in an agricultural, industrial, or post-industrial stage—and in government. Human development indicators (HDI) take into account not only per capita GDP but also such factors as longevity, quality of education, crime rates, and maternal and infant mortality. Currently, Australia and Norway top the HDI list—advanced, modern economies with stable, democratic governments. Zimbabwe, a heavily agricultural nation ruled by a demented thug and his cronies, is dead last.

WHERE WE'RE GOING

The world and the way we use energy are changing at an incredible pace. Fortunately, gaining an understanding of ‘energy’ is neither mysterious nor difficult. There is no need to feel overwhelmed or intimidated by politicians, salesmen, hucksters, or demagogues on energy issues (or any other issues, for that matter).

Many people may feel that ‘science and technology’ have become as foreign as another country, or at least another culture. When we visit another country, we can better appreciate its culture and customs if we can understand something of the language. The terminology of energy and the issues surrounding energy use is all around us: acid rain, greenhouse effect, a head of steam, the China syndrome, meltdown, and semiconductors. It helps to know what such terms mean, just as it helps to know some vocabulary of a different language when visiting a country where that language is spoken.

It's also vital to understand that there are limits as to what can be accomplished with energy. We can't create energy out of nothing. The best we can do is use the energy available to us and convert it from one form to another. Ideally, we would like to convert 100% of the energy from one form to another, with no waste or losses. We'll never really be able to attain this ideal. The profound laws of nature that say that energy cannot be created from nothing, and cannot be converted with 100% efficiency to a different form can be summarized in the statement that, ‘You can't win, and not only that, you can't even break even.’

We must also understand that there are limits to what scientists and engineers can accomplish, and what they can tell us. As an example, reducing the environmental effects associated with using a particular fuel include removing a potential pollutant from the fuel before it is burned, or capturing the pollutant after the fuel has been burned but before it can escape to the environment. Scientists can develop methods for removing or capturing these harmful materials before they impact the environment. Engineers can design plants for employing these methods on a large scale. Economists can calculate the increase in costs (in your electric bill, for example) resulting from building and operating these plants. But none of these people can tell, or calculate, let alone dictate to you, your personal optimum trade-off would be between increased electricity bills or fuel prices on one hand, and accepting greater environmental degradation on the other hand. It is up to the individual citizen, or groups of citizens working together, to choose between, e.g., increased electricity costs vs. forest destruction from loosely regulated pollution from electricity-generating plants. Some might accept substantially higher electric bills in exchange for protecting the environment. Others might adopt the ‘if you've seen one tree, you've seen 'em all’ attitude. The choice is not something that comes from scientific or engineering calculations. The choice is something that each person must make individually.

THE LANGUAGE OF ENERGY

Understanding something of the culture and literature of science requires knowing some of the language used in science. This may seem peculiar at first, because in any country scientists speak the same language as all the other citizens—at least they appear to. Confusion can be caused because sometimes scientists use a common word—energy being a fine example—with a meaning or connotation different from the way the word is used in everyday speech. That's especially because scientists use a variety of jargon and acronyms for efficient communication with colleagues in the same scientific discipline. When reading scientific material or having discussions with scientists, it's important to remember that many words used casually in everyday conversation have more restricted or specialized definitions when used in a scientific context.

All of us hear or read statements like these: ‘I should wash my car today, but I don't have the energy.’ ‘I've converted my house to run on solar energy.’ ‘I have to work all day tomorrow.’ ‘That test was a lot of work!’ ‘A good golfer can hit a ball with a lot of power.’ ‘Oh no! The power just went off!’ Plenty of similar examples can be gleaned from everyday conversations and from the media. A careful look will show that the same words are not being used in quite the same way in each case. Surely the ‘power’ with which a golfer hits a ball is not the ‘power’ that operates the television set and lamps. The ‘energy’ to operate an entire household is surely different from the ‘energy’ a person claims not to have when he or she doesn't want to wash the car.

The definitions of the three key terms—energy, work, and power —that we will use throughout the remainder of this book are more restricted than the ways in which we use them in everyday discourse.

Work is causing an object to move into, or out of, some position, especially when it moves against a resistance.

Some examples of work include: carrying items up stairs, against the resistance of gravity; driving down the road against the resistance of friction in the tires and mechanical parts of the car; fabricating materials into useful objects against their natural strength or stiffness; and sending electricity from a generating station to consumers, against the electrical resistance of the wires. Everything we try to accomplish in our daily lives—in manufacturing, transportation, agriculture—represents doing work. But, to do work, we need energy.

Energy is the capacity for doing work.

Energy is the key to accomplishing, or having the capacity for doing, all of the activities that form the basis of modern society.

It's helpful to think of concepts related to energy using analogies related to money. It's obvious—sometimes painfully—that you can't spend unless you have money. That is, money is the capacity or ability to spend. Money and spending have the same relationship as energy and doing work. We do work to get something done, to accomplish something, to make something happen. We need energy to do this. We spend to acquire goods or services, t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- The Basics

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Energy and us

- 2 Human energy and the energy balance

- 3 Water, wind and kinetic energy

- 4 Heat, steam and thermal efficiency

- 5 Electricity

- 6 Electricity from falling water

- 7 Electricity from steam

- 8 Petroleum, its products, and their engines

- 9 Nuclear energy

- 10 Biomass energy

- 11 Electricity from the wind

- 12 Energy from the sun

- 13 Energy and climate

- 14 The twelve-terawatt challenge

- Further Reading

- Index