![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

This is a book about social cognition. Theory and research that fall under this rubric have captured the imagination and energies of many social and cognitive psychologists since the mid-1970s. Several other books on the topic have appeared (Fiske & Taylor, 1984; Hastie, Ostrom, Ebbesen, Wyer, Hamilton, & Carlston, 1980; Higgins, Herman, & Zanna, 1981; Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1981; Nisbett & Ross, 1980; Wyer & Carlston, 1979) and, more recently, two handbooks have emerged (Sorrentino & Higgins, 1986; Wyer & Srull, 1984). Moreover, a series of “advances” in the area has been established and several journals devote all or many of their pages to the topic. Given this flurry of activity, one might assume that the domain of inquiry is well defined and can easily be differentiated from others. Yet, “What is social cognition?” continues to be one of the most frequently asked questions we receive at colloquia and other speaking engagements. The question is frustrating, as there has never, to our knowledge, been a universally accepted answer. To convey both the objectives and limitations of this book, however, an answer must be provided.

The question actually has two more specific versions. First, what distinguishes social cognition from social psychology more generally? Second, what distinguishes social cognition from cognitive psychology? The answers to these two more specific questions are different. In combination, however, they not only provide a perspective on social cognition, but on what the present volume hopes to accomplish.

Social Cognition and Social Psychology

It can easily be argued that social psychology is the parent (or at least one of them) of contemporary cognitive psychology. The current focus of cognitive psychology on the processing of complex stimulus arrays, and the role that general world knowledge plays, was considered revolutionary when it occurred in the 1970s, replacing the more traditional concern with learning nonsense syllables and unrelated word lists. In social psychology, however, a concern with knowledge representation, and the influence it has on cognitive and social behavior, predates this “revolution” by more than a quarter of a century. A recognition that individual pieces of information are often represented as configural wholes, the meaning of which cannot be captured by examining the constituent elements, dates back to Soloman Asch’s (1946) classic work on impression formation. An analysis of the memory organization of specific subsets of cognitions is reflected in the work of Fritz Heider (1946, 1958/1982), and was a major thrust of social psychological research for many years (cf. Abelson, Aronson, McGuire, Newcomb, Rosenberg, & Tannenbaum, 1968). More general characteristics of cognitive structure such as the differentiation and interrelatedness of the concepts that people have formed in different knowledge domains has its roots in the work of O.J. Harvey (e.g., Harvey, Hunt, & Schroder, 1961), William Scott (1963), and Milton Rokeach (1960). The research on communication and persuasion that was stimulated by Hovland and others in the 1950s (e.g., Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953) was obviously concerned with the manner in which the information one receives affects judgments and decisions, as was research on attitude and belief change more generally (for summaries of the early theories and research, see Insko, 1967; Wyer, 1974). More recent work on impression formation (e.g., Anderson, 1971) and attribution (e.g., Kelley, 1967; Jones, Kanouse, Kelley, Nisbett, Valins, & Weiner, 1971/1987) was also concerned with the cognitive bases of social judgment.

In short, much of social psychology has been oriented around cognitive issues and questions. What, then, is new about social cognition? The answer, we believe, lies simply in the emphasis that social cognition theory places on process or, more accurately, processes. That is, social cognition, unlike cognitive social psychology of the type described above, takes as its objective a specification of the component cognitive operations that underlie the acquisition of social information and, along with preexisting knowledge, its use in making a judgment or decision.

To imply that the earlier research on impression formation, communication and persuasion, and attitude and belief change was not concerned with these matters may seem curious, if not contradictory. Any viable conceptualization of the manner in which information influences beliefs, attitudes, and behavior must make some assumptions about the cognitive processes that underlie these effects. In fact, however, the research that was performed seldom evaluated these assumptions directly, nor did it attempt to identify the particular point in the overall sequence of cognitive operations at which the observed effects were localized.

In contrast, the focus of social cognition is precisely on the cognitive mechanisms that mediate judgments and behavior. The sequence of these operations is usually assumed to be divisible into several component processing stages. These include:

1. the interpretation of individual pieces of information in terms of previously formed concepts or knowledge;

2. the organization of information in terms of a more general body of social knowledge, and the construction of a cognitive representation of the person, object, or event to which the information pertains;

3. the storage of this cognitive representation in memory;

4. the retrieval of the representation, along with other judgment-relevant knowledge, at the time a judgment is anticipated;

5. the combining of the implications of various features of the representation to arrive at a subjective inference; and

6. the transformation of the subjective inference into a response (e.g., judgment or behavioral decision).

The effect of a situational variable on an overt response could be localized in any one of these stages (or several of them for that matter). Moreover, the specific cognitive operations that are performed may differ in the type and amount of information that is acquired. They may also depend on the processing objectives of the individual and the time at which a response is required.

Although early social psychological research was often concerned with phenomena at one stage or another, the processing of information at this stage was seldom isolated, either theoretically or empirically, from the effects of processing at other stages. Nor was was an analysis provided for how the various processes operate in concert to generate a judgment or decision. For example, several principles of cognitive consistency (Abelson & Rosenberg, 1958; Festinger, 1957; Heider, 1958/1982; McGuire, 1960; Osgood & Tannenbaum, 1955) were postulated to govern the organization of beliefs and attitudes and the consequences of information bearing on one cognition on others that were related to it. However, it was never clear from the research whether the observed effects were the result of changes in the representation of interrelated beliefs and attitudes (which would presumably occur at the encoding and/or organizational stages) or the result of inferences that were made at the time of judgment.

Similarly, research on communication and persuasion was often concerned with the effects of the order in which arguments were presented (Miller & Campbell, 1959), the relative influence of emotional versus factual content (Janis & Feshbach, 1953), and the relative impact of informational variables versus source characteristics (Tannenbaum, 1967). However, whether these variables had their impact because they influenced the interpretation of information at the time it was first received, because they induced selective attention and encoding of the information, or because they affected the way that different pieces of information were combined to make a judgment was never established—or even pursued. Indeed, only William McGuire’s (1964, 1968, 1972) work reflected a systematic attempt to understand the component processes that underlie responses to persuasive messages, to isolate the situational and informational factors that influence each process, and to specify how these processes act together to produce judgments.

Research in person impression formation has always been concerned with the manner in which different pieces of information combine to affect liking for the person. A conceptualization of these processes requires assumptions about the evaluative implications that are attached to each component piece of information and the relative importance (weight) that is given to each. Historically, however, the data used to evaluate these processes consisted only of liking judgments. These judgments were in turn based on factorially organized sets of stimulus adjectives, the weights and scale values of which (as well as the process for combining them) were inferred post hoc from the pattern of judgments that emerged (Anderson, 1965, 1970, 1981). Thus, no direct evidence was obtained for any of the processes that were postulated.1

In contrast to each of these traditions, social cognition theorists often design experiments that are intended to tap directly into one of the various stages of processing that underlie judgmental phenomena. In doing so, they recognize that a process cannot usually be isolated solely on the basis of judgment data. Just as the cognitive psychologist recognizes that behavior is only one link in a long chain of responses, the social cognition theorist recognizes that judgments (or behavioral decisions) are only the final link in a long psychological chain.

It is often important to understand the factors that affect the initial interpretation of information. To do this, one might obtain information about the types of concepts that subjects use to encode the stimuli into memory, as reflected in think-aloud protocols or open-ended descriptions of the objects. Alternatively, one might examine the time required to make concept-related judgments, or differences between the original information and later reports when subjects are asked to recall it.

Similarly, theorists are often concerned with the nature of the cognitive representations that are formed and the way they are stored in memory. Thus, they may examine the amount and type of information that is later recalled, as well as the order in which items are produced and the latencies between responses. Under some circumstances, it is likely to require an assessment of the cognitions (elaborations, counterarguments, etc.) that subjects generate in response to the information and are likely to include in its representation.

Finally, an understanding of the factors that underlie the transformation of subjective inferences into overt responses may require not only knowledge of the response that is made to the particular stimulus, but also responses that are made to other, objectively irrelevant stimuli. These latter responses can provide evidence of the rules that subjects are using to transform their subjective judgments into overt responses.

It is sad but true: cut into a long chain of responses and the chain is destroyed. To put it another way, not all of the processes we have enumerated can be investigated in a single experiment. Thus, a research strategy must by developed that permits the processes at each stage to be identified and isolated. At the same time, however, a general conceptualization must be developed that will permit each of the component processes to be fit together into a functioning system. Such a conceptualization must specify, in general information processing terms, how the various processes interact. This is the ultimate objective of social cognition theory and research.

Social Cognition and Cognitive Psychology

The second issue to be raised is what distinguishes social cognition from cognitive psychology. At one level, both are concerned with the various stages of information processing we have outlined above. At another level, however, there are important differences.

One difference is that some cognitive processes are more important (i.e., capture more variance) than others in social interaction. While a cognitive psychologist may be very concerned about whether two meanings of a homophone can be activated simultaneously, or whether the stimulus suffix effect is due to a separate auditory store, or whether the time required to do mental rotation decreases with practice, social cognition theorists are relatively unconcerned with such matters (cf. Hamilton, in press). To the degree they shed light on how the cognitive system operates, they are, at some level, relevant. At the same time, however, their relevance is indirect and sometimes difficult to understand given our current knowledge.

Another difference is that cognitive psychologists are often concerned with the capacity of the cognitive system (cf. Holyoak & Gordon, 1984). How fast, how accurate, how far can the system be pushed before performance is destroyed? These are questions that are often pursued by cognitive psychologists, and some of the historical reasons for this have been outlined elsewhere (Lachman, Lachman, & Butterfield, 1979). The important point is that social cognition theorists are much more concerned with how the system actually operates within a given ecological context. To a much greater extent, we are concerned with what does happen rather than what can happen. Another difference between the two disciplines is that they focus on different end states. Although this is not an all-or-none issue, cognitive psychology gives much more emphasis to comprehension and learning. There is a much greater concern with sensory information, how it is picked up from the environment, encoded, comprehended, and ultimately represented within the cognitive system. In contrast, social cognition theorists give more weight to understanding how people make various judgments and behavioral decisions. Because of this, they are more concerned with specifying which aspects of the information that people receive are actually used, as well as how they are used.

These differences are important because they often produce differences in the task objectives that subjects are given in the research that is performed. This, in turn, produces differences in the results that emerge and the theories that are used to account for them. If there is one thing that we have learned from the past decade of social cognition research, it is that on-line processing objectives have an important impact on the interpretation that is given to information, the representations that are formed from it, and the features of the information that are most likely to be recalled (for a review of this literature, see Srull & Wyer, 1986). Because of this, there will often be differences in the paradigms used, the results obtained, and the theories developed by cognitive psychologists and social cognition researchers.

An Overview of Social Cognition Research

Many differences in task objectives occur at the input stages of processing. They are reflected in the initial interpretation of information, the subset of previously acquired knowledge that is used for organizing it and construing its implications, and the representation of it that is ultimately stored in memory. To the degree that theories in cognitive psychology fail to account for these effects, their relevance to social cognition is limited. While we believe that many of these factors have been ignored or deemphasized in cognitive psychology, we also believe that theories of information retrieval have highlighted many of the processes that occur in social settings. Thus, existing theories of retrieval processes (e.g., Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1980, 1981; Gillund & Shiffrin, 1984) may actually be of greater relevance to contemporary social cognition.

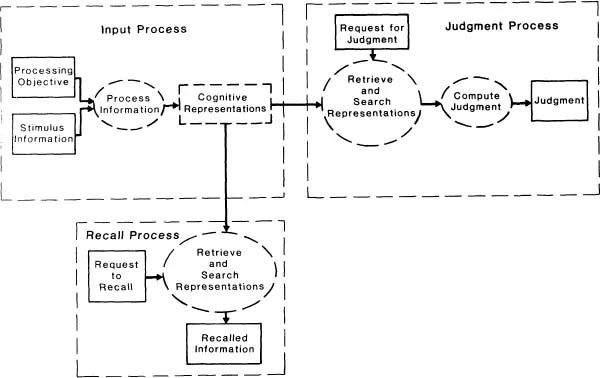

Figure 1.1 Relations among various components of social judgment. Observable (independent and dependent) variables are enclosed by solid lines, and mediating variables by dashed lines. Rectangles denote “states” and ovals denote “processes.”

Some of these considerations are summarized in Figure 1.1. The figure indicates the relations among independent and dependent variables of concern in both cognitive and social psychology, as well as the hypothetical constructs that mediate their relation. Independent and dependent variables are enclosed in solid lines, and the hypothetical mediators in dashed-lines. Each pathway connecting two variables reflects a relation that must be specified by any theory of cognitive functioning. The diagram is obviously incomplete. As just one example, it does not include the influence of general world knowledge. Several observations can be made with reference to the diagram:

1. The processing t...