![]()

CHAPTER 1

Prototypes and categories

1.1 Colours, squares, birds and cups: early empirical research into lexical categories

The world consists of an infinite variety of objects with different substances, shapes and colours. How do we translate this variety into manageable word meanings and why do we succeed even where no clear-cut distinctions seem to be available, such as between the colours ‘red’ and ‘orange’ or ‘green’ and ‘blue’? Experimental psychology has shown that we use focal or prototypical colours as points of orientation, and comparable observations have also been made with categories denoting shapes, animals, plants and man-made objects.

Moving through the world we find ourselves surrounded by a variety of different phenomena. The most eye-catching among them are organisms and objects: people, animals, plants and all kinds of everyday artefacts such as books, chairs, cars and houses. In normal circumstances we have no difficulty in identifying and classifying any of them, and in attributing appropriate class names to them. However, it is not so easy to identify, classify and, as a consequence, to name other types of entities, for instance parts of organisms. Knees, ankles and feet of human beings and animals or the trunk, branches and twigs of a tree belong to this type. It may be fairly clear that one’s kneecap belongs to one’s knee and that the trunk of a tree includes the section which grows out of the ground. Yet at which point does one’s knee end and where does one’s thigh start? Where does a trunk turn into a treetop and where does a branch turn into a twig? Similar problems arise with landscape names, and words denoting weather phenomena. Who can tell at which particular spot a valley is no longer a valley but a slope or a mountain? Who can reliably identify the point where drizzle turns into rain, rain into snow, where mist or fog begins or ends?

When we compare the two types of entities mentioned, we find that they differ with respect to their boundaries. Books, tables, cars and houses are clearly delimited objects. In contrast, the boundaries of entities like knee, trunk, valley and mist are far from clear; they are vague. This vagueness has troubled philosophers and linguists interested in the relationship between word meanings and extra-linguistic reality, and has given rise to various theories of vagueness’.* Yet in spite of their vagueness, we have the impression that these boundaries exist in reality. A kneecap cannot be included in the thigh, and a mountain top will never be part of a valley. So classification seems to be forced upon us by the boundaries provided by reality.

However, there are phenomena in the world where this is not the case. Take physical properties such as length, width, height, temperature and colours, all of them uninterrupted scales extending between two extremes – how do we know where to draw the line between cold, warm and hot water? And how do we manage to distribute the major colour terms available in English across the 7,500,000 colour shades which we are apparently able to discriminate (see Brown and Lenneberg 1954: 457)? The temperature scale and the colour continuum do not provide natural divisions which could be compared with the boundaries of books, cars, and even knees or valleys.

Therefore the classification of temperature and colours can only be conceived as a mental process, and it is hardly surprising that physical properties, and colours especially, have served as the starting point for the psychological and conceptual view of word meanings which is at the heart of cognitive linguistics. This mental process of classification (whose complex nature will become clearer as we go on) is commonly called categorization, and its product are the cognitive categories, e.g. the colour categories RED, YELLOW, GREEN and BLUE, etc. (another widely used term is ‘concept’).

What are the principles guiding the mental process of categorization and, more specifically, of colour categorization? One explanation is that colour categories are totally arbitrary. For a long time this was what most researchers in the field believed. In the 1950s and 1960s, anthropologists investigated cross-linguistic differences in colour naming and found that colour terms differed enormously between languages (Brown and Lenneberg 1954; Lenneberg 1967). This was interpreted as a proof of the arbitrary nature of colour categories. More generally, it was thought to support the relativist view of languages, which, in its strongest version as advocated by Whorf, assumes that different languages carve up reality in totally different ways.2

A second explanation might be that the colour continuum is structured by a system of reference points for orientation. And indeed, the anthropologists Brent Berlin and Paul Kay (1969) found evidence that we rely on so-called focal colours for colour categorization. Berlin and Kay’s main target was to refute the relativist hypothesis by establishing a hierarchy of focal colours which could be regarded as universal. To support the universalist claim they investigated 98 languages, 20 in oral tests and the rest based on grammars and other written materials. In retrospect, their typological findings, which in fact have not remained uncriticized, have lost some of their glamour. However, the notion of focal colours, which emerged from the experiments, now appears as one of the most important steps on the way to the prototype model of categorization. We will therefore confine our account of Berlin and Kay’s work to aspects relevant for the prototype model, at the expense of typological details.3

Focal colours

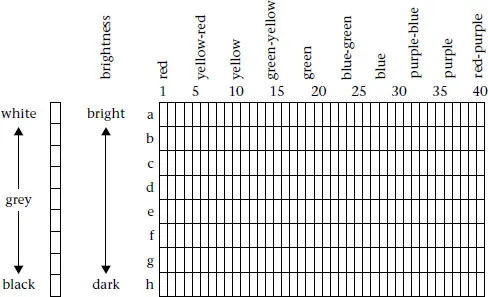

Like other researchers before them, Berlin and Kay worked with so-called Munsell colour chips provided by a company of the same name. These chips are standardized for the three dimensions which are relevant for our perception of different colours, namely hue, brightness and saturation, of which mainly the first two were tested. The advantage of using such standardized colour samples rather than pieces of dyed cloth is that anthropological and psychological tests become more objective, since they can be repeated by other researchers and the findings of different tests can be compared. The set of chips used by Berlin and Kay was composed of 329 colour chips, 320 of which represented 40 different colours, or, more precisely, 40 hues, each divided up into eight different levels of brightness. The remaining nine chips were white, black, and seven levels of grey. The chips were set out on a card in the manner shown in Figure 1.1. The vertical axis in the figure displays the various shades of brightness of one identical hue. On the horizontal axis the chips are ordered in such a way that starting from red the hues move through yellow-red to yellow through green-yellow to green and so on.

With the help of the colour card Berlin and Kay set about testing how speakers of the 20 selected languages categorized colours. In doing so, they were not so much interested in the colour vocabulary in general, but rather in a particular set of colour terms which met the following criteria: the terms should consist of just one word of native origin (as opposed to greenish-blue and turquoise); their application should not be restricted to a narrow class of objects (as opposed, e.g., to English and German blond); the words should come to mind readily and should be familiar to all or at least to most speakers of a language (as opposed to, say, vermilion, magenta or indigo). Colour terms which fulfilled these criteria were called basic colour terms. In the first stage of the experiments, Berlin and Kay collected the basic colour terms of the 20 languages. This was achieved by means of a ‘verbal elicitation test’, which is just a more complicated way of saying that speakers of the respective languages were asked to name them. In the second stage, these speakers were shown the colour card and asked to point out

Figure 1.1 Arrangement of Munsell colour chips used by Berlin and Kay (numbers and letters added)

1. all those chips which [they] would under any conditions call x

2. the best, most typical examples of x.

(Berlin and Kay 1969: 7)

The questions show that, unlike Lenneberg and other anthropologists before them, Berlin and Kay were not only interested in the extension of colour categories, but also in their best examples. One might even say that what was later called ‘prototype’ is anticipated in the wording of their second question.

What were Berlin and Kay’s findings? In categorizing colours, people rely on certain points in the colour space for orientation. For example, when speakers of English were asked for the best example of the colour ‘red’, they consistently pointed to colour chips in the lower, i.e. darker, regions under the label ‘red’ (f3 and g3 in Figure 1.1; of course, in the tests no colour terms were given on the card). For yellow, informants consistently selected chips with the second degree of brightness under the label ‘yellow’ (b9 in Figure 1.1). These chips (or regions in the colour space), which were thought of as best examples by all or by most speakers of English, were called ‘foci’ by Berlin and Kay.

Foci or focal colours were also found for the other 19 languages. When the focal colours were compared, the result was amazing. Focal colours are not only shared by the speakers of one and the same language but they are also very consistent across different languages. Whenever a language has colour terms roughly corresponding to the English colour terms, their focal points will be in the same area. And even in languages with a smaller number of basic colour terms than English, the best examples of these fewer categories will agree with the respective focal colours of ‘richer’ languages like English.

In sum, there is compelling evidence that instead of being arbitrary, colour categorization is anchored in focal colours. While the boundaries of colour categories vary between languages and even between speakers of one language, focal colours are shared by different speakers and even different language communities.

As is often the case with important scientific findings, the discovery of focal colours not only helped to solve one problem but also raised a number of new questions. Are focal colours to be treated as a phenomenon which is a matter of language or of the mind? What, assuming the latter, is their psychological status? And finally, are ‘foci’ (focal points) restricted to colours or can they be found in other areas as well? These questions will be taken up in the following sections.

The psychological background of focal colours

From a psychological standpoint the categorization of natural phenomena is a rather complex task involving the following processes:4

1. Selection of stimuli Of the wealth of stimuli which are perceived by our sensory systems (visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory), only very few are selected for cognitive processing, i.e. they attract our attention.

2. Identification and classification This is achieved by comparing selected stimuli to relevant knowledge stored in memory.

3. Naming Most cognitive categories are given names though some remain unlabelled, e.g. ‘things to eat on a diet’, ‘things to pack in a suitcase’.

(Barsalou 1987: 102)

Most of these aspects were investigated by Eleanor Rosch, who in the early 1970s set out to explore the psychological background of focal colours.5 As a psychologist, her primary aim was to find out whether focal colours were rooted in language or in pre-linguistic cognition. Her idea was that a cognitive status might be claimed for focal colours if they could be proved to be prominent in the cognitive processes involved in categorization.

Starting out from the most basic of the three cognitive processes, Rosch first examined whether focal colours are perceptually salient. To eliminate the influence of purely language-based categorization, she required informants who had stored as little knowledge of colour names and related colour categories as possible. So she decided to work with pre-school children and with members of a non-Westernized culture in Papua New Guinea, the Dani. Earlier research had shown that Dugum Dani, the language spoken by the Dani, contained only two basic colour terms, in contrast to the 11 basic colour terms available to speakers of English (Heider 1971). Like children, the Dani were therefore particularly well suited as uncorrupted informants for colour-categorizing experiments. English-speaking adults, who were supposed to have the full system of basic colour terms at their disposal, were only used as control groups in some of the tests.

Rosch’s first experiment (Heider 1971), which was to test the arousal of attention (or stimulus selection), was dressed up as a ‘show me a colour’ game. She gave 3-year-old children arrays of colour chips consisting of one focal colour, as found by Berlin and Kay, and seven other chips of the same hue, but other levels of brightness. The children were told that they were to show the experimenter any colour they liked. The reasoning behind this game was that young children’s attention would be attracted more readily by focal colours than by other colours. In fact, it turned out that the children did pick out focal chips more frequently than non-focal chips. The preponderance of the focal chips was particularly...